Chinese and Indian Multinationals: Do Their Shopping Sprees in Advanced Countries Make Them More Innovative?

Chinese multinationals are

continuously expanding their operations in Europe and the USA through

cross-border acquisitions (CBAs), with the aim of tapping into

international knowledge located in target firms and innovative hubs.

Amendolagine, Giuliani, Martinelli and Rabellotti have looked into the

innovative impacts that CBAs have on the acquiring multinational

enterprises (MNEs), asking whether they innovate after they have

acquired advanced countries’ innovative firms and have invested in

regions with high innovative capacity. They find that MNEs with strong

knowledge bases and high-status standing can gain from CBAs, the rest

remain stranded, no matter how innovative their target firm or location

is.

Roughly 40% of emerging economies’ investments are in advanced countries (UNCTAD, 2017) that are rich in strategic assets such as patents and technological skills. Landmark examples of emerging market multinational enterprises’ (EMNEs) asset-seeking cross-border acquisitions (CBAs) are the state-owned Chinese chemical company ChemChina’s takeovers of the Italian tire producer Pirelli in 2015 and the Swiss pesticide and seed producer Syngenta in 2016. These kinds of CBAs are expected to boost the acquiring EMNEs’ innovative capabilities and promote processes of reverse knowledge transfer to their home countries (Hansen et al., 2016). Such processes could probably help emerging economies, such as China, catch up technologically and grow economically, but would in parallel engender a” hollowing out” risk in the so-called advanced economies, which may lose control of some of their strategic assets. This latter issue has sparked concerns and intense policy debate that has led some governments to start thinking about protecting those assets and limiting the inflows of direct investments in certain industries. Yet we know little about the extent to which EMNEs benefit from their CBAs, as the existing literature is limited and inconclusive (Anderson et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2018; Piperopoulos et al., 2018).

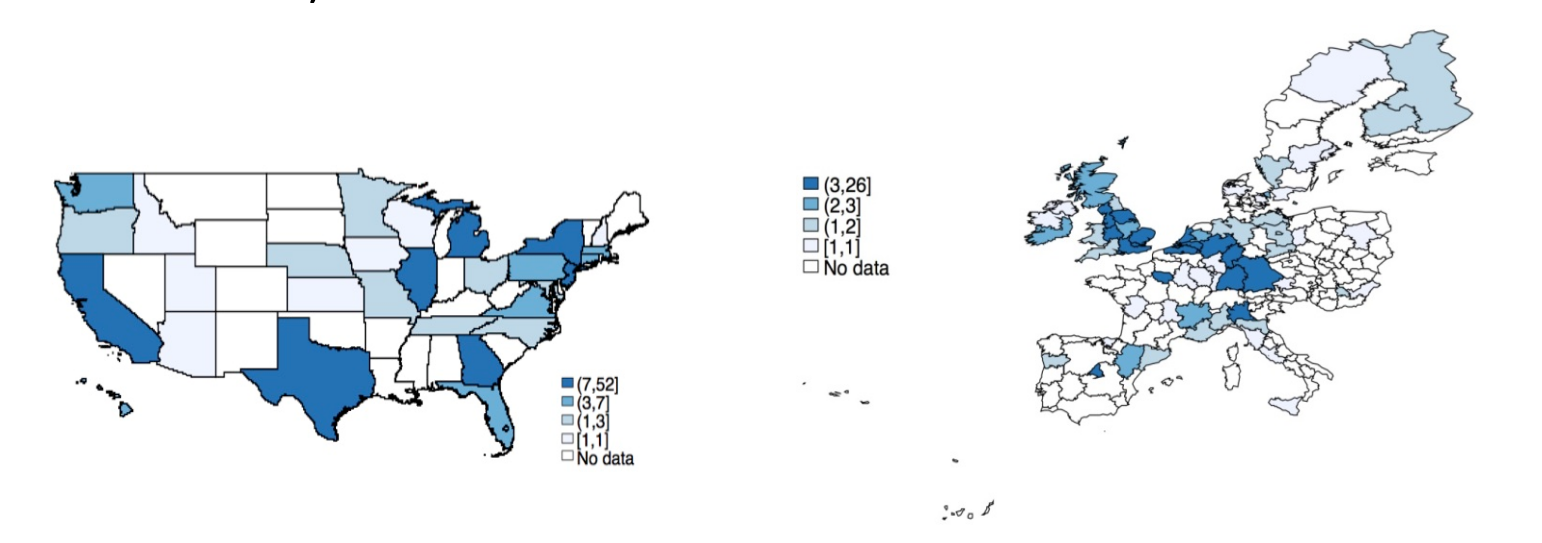

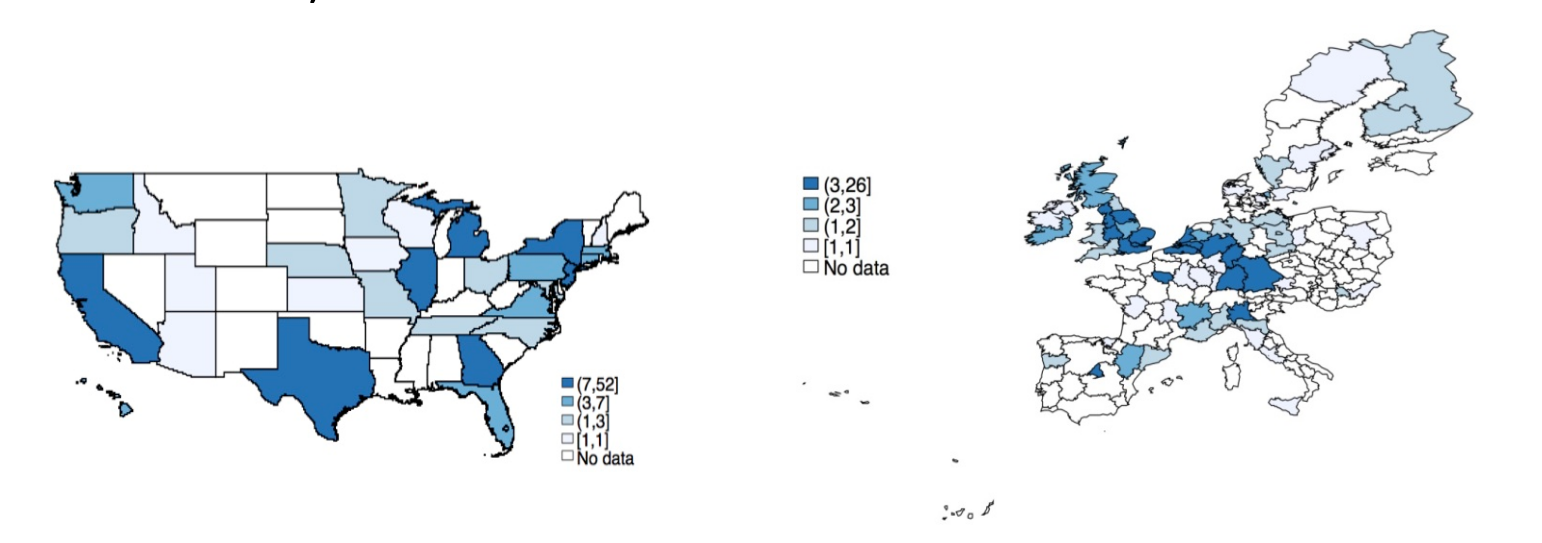

In Amendolagine et al. (2018) we contribute to this ongoing research agenda by asking: Do EMNEs innovate more post-deal when the innovative capacity of target firms and/or regions is higher? Does EMNEs’ absorptive capacity and status positively moderate the relationship between their post-deal innovative output and the innovative capacity of the target firm and/or region? The empirical analysis is carried out on a sample of all majority-stake CBAs by Chinese and Indian firms in Europe (EU28) and the United States between 2003 and 2011, from the Zephyr (Bureau van Dijk) and SDC Platinum (Thompson) databases. The focus is on medium- and high-tech manufacturing and service industries, which are most likely to aim to acquire and build on the target firm’s and region’s technological assets. The period observed includes 455 deals, mostly in the manufacturing sector. Overall, the preferred target area is the United States, which accounts for 206 deals, mainly in California, and followed by New York, New Jersey, and Texas. In Europe, the United Kingdom is the preferred target, accounting for 87 deals, mostly in the London area; the second-most-preferred destination is Germany, where acquisitions are concentrated in Bayern and Baden-Württemberg. Figure 1 below depicts the geographical distributions of acquisitions.

Our baseline expectation is that the higher the innovative capacity of the target firm or the target region, the more the acquiring firm will innovate post-acquisition. EMNEs that invest in innovation-intensive firms will access a pool of unique skills and technological capabilities that the target firm has accumulated over time (Dosi, 1988), which will result in a higher innovative output by the EMNE after the acquisition. Similarly, we expect that EMNEs will learn more from investing in knowledge-rich and innovative hubs compared with less-innovative areas. In particular, we refer to the magnitude of the learning opportunities engendered by the pool of specialized labour and innovative firms, or other localized capabilities that generate an environment favorable to knowledge enhancing spillovers (Bathelt et al., 2004).

Unexpectedly, we find that the output variable, which is the EMNE’s post-acquisition innovation capacity (measured by the patents registered in the 3 years after the deal) is negatively and significantly associated with the target firm’s innovative capacity (measured by its patents in the 5 years before the deal). More precisely, we find that one patent more in the target company is associated, on average, with a reduction of 2.4% in the expected innovative output. In turn, the relationship between the output variable and the region-level innovation is positive and significant, when measuring the latter with a composite indicator of how the local ecosystem is more or less favorable for innovation and knowledge circulation (Crescenzi et al., 2007).

The Moderating Role of EMNE Knowledge Base

Our baseline relationships assumed that acquiring EMNEs have homogeneous strong absorptive capacities, allowing easy absorption and extension of the target firm’s and region’s knowledge. However, emerging country firms may have accumulated very different absorptive capacities needed for the successful acquisition of new knowledge from the host location (Bell and Pavitt, 1993) and to establish learning links to local actors (Marin and Bell, 2006).

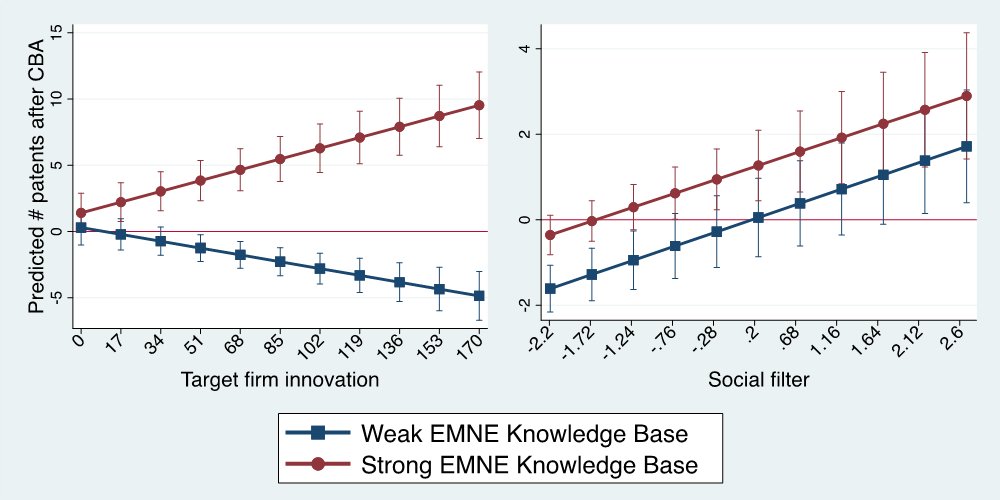

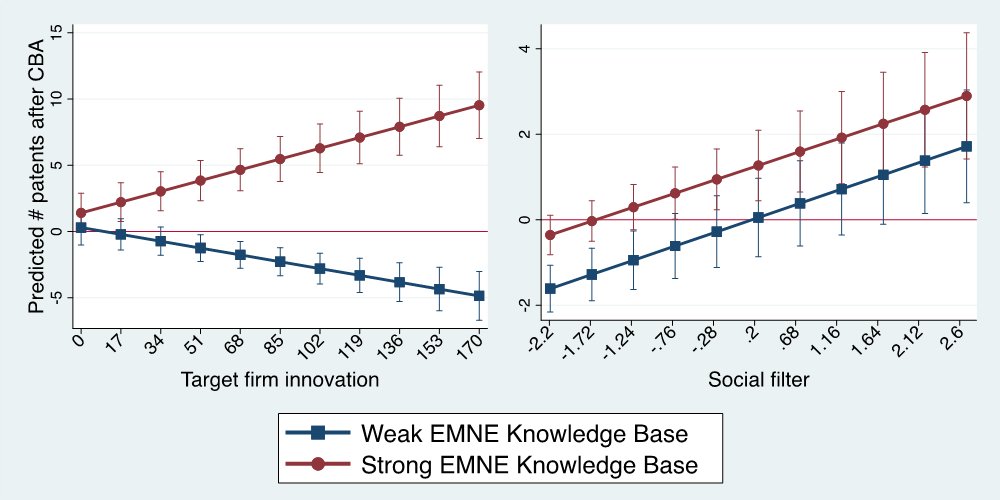

When we account for these differences, the empirical tests show that the negative baseline relationship between the target firm’s innovative capacity and EMNE post-acquisition innovative output is less negative the stronger the EMNE’s knowledge base prior to the acquisition, measured as the patents of the acquirer in the 5 years before the deal plus the number of the cited patents, following Ahuja and Katila (2001) (Figure 2).

Note: Weak EMNE knowledge base corresponds to the variable equal to 0. Strong EMNE knowledge base corresponds to the 95th percentile of the variable’s distribution

In terms of the relationship between the output variable and the level of innovation in the region, we found that the EMNE knowledge base is a positive and significant moderator for large enough values of the regional social filter, which measures the degree to which the target region offers an ecosystem favorable to innovation (Rodriguez-Pose and Crescenzi, 2008). As shown in Figure 2, at each level of the social filter, predicted outputs for low-knowledge base EMNEs are lower than the outputs predicted for EMNEs with high knowledge bases.

The Moderating Role of EMNE Knowledge Status

Drawing on the social status theory (Podolny, 1993; Gould, 2002) we contend that EMNE status influences successful integration between the target and acquiring firms in a CBA (Sharkey, 2014). Because our analytical context is that of internationalizing firms, we understand status as reflected by the international press, which we assume to be an important source of signals influencing status considerations by international audiences in the target firm or region. Therefore, we measure status as a standardized residual of a regression with the number of positive news stories about the acquiring EMNE as a dependent variable and a set of firm-level variables as regressors that capture EMNEs’ observable characteristics related to status (e.g. size, innovativeness, profitability, country of origin) (Shen et al., 2014).The intuition is that the uncertainty over the quality of the acquiring EMNEs can make managers wary, not because they are intimidated by the country of origin but rather because information about them may be limited. An Italian manager working for a company recently acquired by a Chinese multinational confirms this point: “Prior to the acquisition we did not know the firm: the acquisition was a bolt from the blue, so we [middle managers] immediately went to see the press . . . to see whether it talked about the firm, but we did not find much . . . of course we knew it was not a bad monster, we had been in China before so we were not scared by Chinese firms, but still there was a great uncertainty there because we did not know much about the firm.”

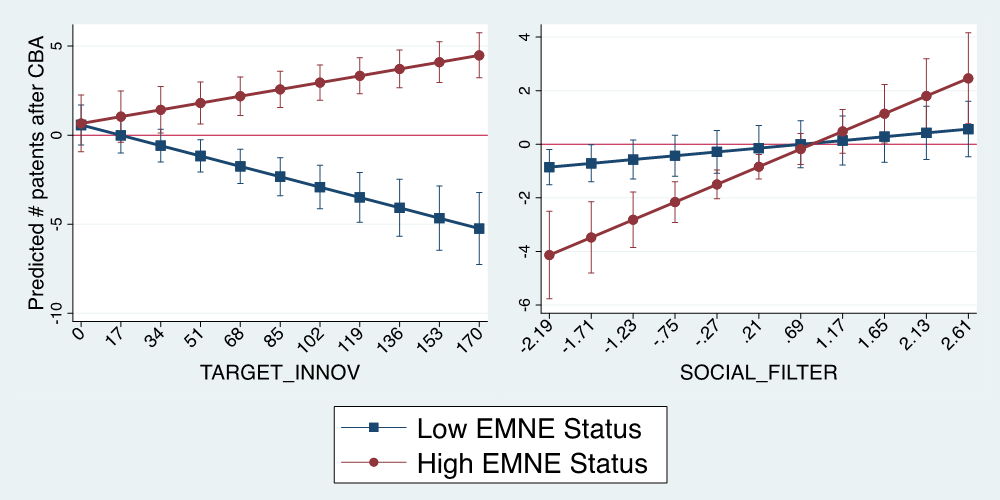

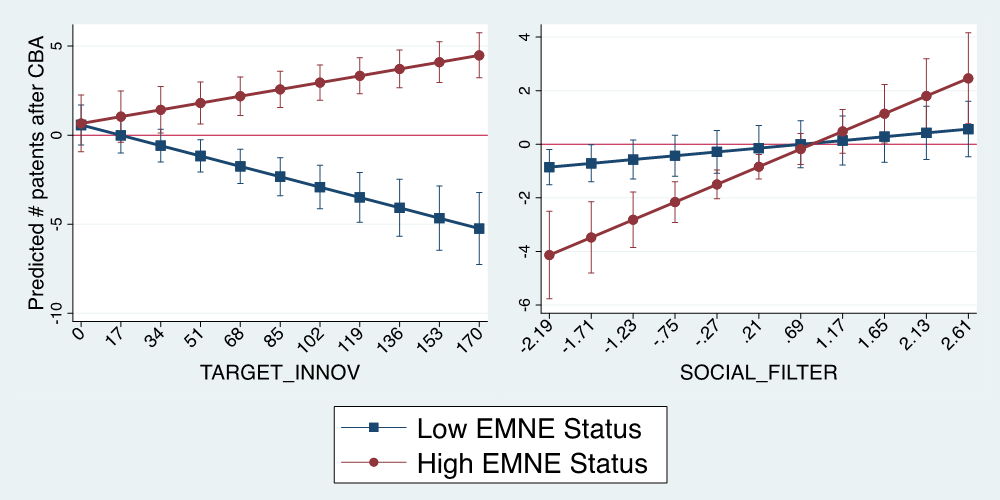

Insights from our interviews also suggest that skepticism seems to be firm-specific rather than country-specific, while information provided by the media is potentially useful for reducing this uncertainty and creating a more-positive climate for cooperation by reassuring managers at the target firm and in the host location about the quality of the acquiring firm and mitigating fears of being outcompeted as the result of reverse knowledge transfer (Anderson et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2018). We expect that this will have a positive impact on post-acquisition innovation. Our econometric results show the statistical significance of the positive moderating role of high EMNE status, presented in Figure 3.

Note: Low status corresponds to the 5th percentile of the variable distribution, while high status corresponds to the 95th percentile.

Conclusions

Our results show that EMNEs do not always benefit from investing in innovative target firms and regions and that acquisitions are not an easy fix for technological laggards. Some time ago, The Economist described EMNEs as “new creatures, bursting out of nowhere to take the world by storm.” We suggest that the extent to which this actually happens largely depends on their firm-specific history of accumulation of knowledge and on their social status and consensus building. Only an elite number of EMNEs can make it; the rest remain stranded, no matter how innovative their target firm or location.

Ahuja G., Katila R. (2001) Technological acquisitions and the innovation performance of acquiring firms: a longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 23:197-220.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/smj.157

Amendolagine, V., Giuliani, E., Martinelli, A., Rabellotti; R. (2018) Chinese and Indian MNEs’ shopping spree in advanced countries. How good is it for their innovative output? Journal of Economic Geography, 18: 1149–1176.

https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/18/5/1149/5123432

Anderson J., Sutherland D., Severe, S. (2015) An event study of home and host country patent generation in Chinese MNEs undertaking strategic asset acquisitions in developed markets. International Business Review, 24: 758-771.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0969593115000244?via%3Dihub

Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., Maskell, P. (2004) Clusters and knowledge: local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28: 31–56.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

Bell, M., Pavitt, K. (1993) Technological accumulation and industrial growth: contrasts between developed and developing countries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 2: 157–210.

https://academic.oup.com/icc/articleabstract/2/2/157/888431?redirectedFrom=PDF

Crescenzi, R., Rodrıguez-Pose, A., Storper, M. (2007) The territorial dynamics of innovation: a Europe–United States comparative analysis. Journal of Economic Geography, 7: 673–709.

https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/7/6/673/960929

Dosi, G. (1988) Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. Journal of Economic Literature, 26: 1120–1171.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2726526?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Fu, X., Hou, J., Liu, X. (2018) Unpacking the relationship between outward direct investment and innovation performance: evidence from Chinese firms. World Development, 102: 111-123.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X17303145?via%3Dihub

Giuliani E. (2007) The selective nature of knowledge networks in clusters: evidence from the wine industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 7: 139-68.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X17303145?via%3Dihub

Gould, R. V. (2002) The origins of status hierarchies: a formal theory and empirical test. The American Journal of Sociology, 107: 1143–1178.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/341744

Hansen, U., Fold, N., Hansen, T. (2016) Upgrading to lead firm position via international acquisition: learning from the global biomass power plant industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 16: 131–153.

https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/16/1/131/2412644

Marin, A., Bell, M. (2006) Technology spillovers from foreign direct investment (FDI): the active role of MNC subsidiaries in Argentina in the 1990s. Journal of Development Studies, 42: 678–697.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220380600682298

Piperopoulos, P., Wu, J., Wang, C. (2018) Outward FDI, location choices and innovation performance of emerging market enterprises. Research Policy, 47: 232–240.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733317301865?via%3Dihub

Podolny, J. M. (1993) A status-based model of market competition. American Journal of Sociology, 98: 829–872.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/230091

Rodriguez-Pose, A., Crescenzi, R. (2008) R&D, spillovers, innovation systems and the genesis of regional growth in Europe. Regional Studies, 42: 51–68.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00343400701654186

Sharkey, A. J. (2014) Categories and organizational status: the role of industry status in the response to organizational deviance. American Journal of Sociology, 119: 1380–1433.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/675385

Shen, R., Tang, Y., Chen, G. (2014) When the role fits: how firm status differentials affect corporate takeovers. Strategic Management Journal, 35: 2012–2030.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/smj.2194

UNCTAD. (2017) World Investment Report. Geneva: UNCTAD.

https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2017_en.pdf

Roughly 40% of emerging economies’ investments are in advanced countries (UNCTAD, 2017) that are rich in strategic assets such as patents and technological skills. Landmark examples of emerging market multinational enterprises’ (EMNEs) asset-seeking cross-border acquisitions (CBAs) are the state-owned Chinese chemical company ChemChina’s takeovers of the Italian tire producer Pirelli in 2015 and the Swiss pesticide and seed producer Syngenta in 2016. These kinds of CBAs are expected to boost the acquiring EMNEs’ innovative capabilities and promote processes of reverse knowledge transfer to their home countries (Hansen et al., 2016). Such processes could probably help emerging economies, such as China, catch up technologically and grow economically, but would in parallel engender a” hollowing out” risk in the so-called advanced economies, which may lose control of some of their strategic assets. This latter issue has sparked concerns and intense policy debate that has led some governments to start thinking about protecting those assets and limiting the inflows of direct investments in certain industries. Yet we know little about the extent to which EMNEs benefit from their CBAs, as the existing literature is limited and inconclusive (Anderson et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2018; Piperopoulos et al., 2018).

In Amendolagine et al. (2018) we contribute to this ongoing research agenda by asking: Do EMNEs innovate more post-deal when the innovative capacity of target firms and/or regions is higher? Does EMNEs’ absorptive capacity and status positively moderate the relationship between their post-deal innovative output and the innovative capacity of the target firm and/or region? The empirical analysis is carried out on a sample of all majority-stake CBAs by Chinese and Indian firms in Europe (EU28) and the United States between 2003 and 2011, from the Zephyr (Bureau van Dijk) and SDC Platinum (Thompson) databases. The focus is on medium- and high-tech manufacturing and service industries, which are most likely to aim to acquire and build on the target firm’s and region’s technological assets. The period observed includes 455 deals, mostly in the manufacturing sector. Overall, the preferred target area is the United States, which accounts for 206 deals, mainly in California, and followed by New York, New Jersey, and Texas. In Europe, the United Kingdom is the preferred target, accounting for 87 deals, mostly in the London area; the second-most-preferred destination is Germany, where acquisitions are concentrated in Bayern and Baden-Württemberg. Figure 1 below depicts the geographical distributions of acquisitions.

Figure 1: Geographical Distribution of CBAs in the United States and Europe (NUTS2 in EU28 and States in the USA)

Unexpectedly, we find that the output variable, which is the EMNE’s post-acquisition innovation capacity (measured by the patents registered in the 3 years after the deal) is negatively and significantly associated with the target firm’s innovative capacity (measured by its patents in the 5 years before the deal). More precisely, we find that one patent more in the target company is associated, on average, with a reduction of 2.4% in the expected innovative output. In turn, the relationship between the output variable and the region-level innovation is positive and significant, when measuring the latter with a composite indicator of how the local ecosystem is more or less favorable for innovation and knowledge circulation (Crescenzi et al., 2007).

The Moderating Role of EMNE Knowledge Base

Our baseline relationships assumed that acquiring EMNEs have homogeneous strong absorptive capacities, allowing easy absorption and extension of the target firm’s and region’s knowledge. However, emerging country firms may have accumulated very different absorptive capacities needed for the successful acquisition of new knowledge from the host location (Bell and Pavitt, 1993) and to establish learning links to local actors (Marin and Bell, 2006).

When we account for these differences, the empirical tests show that the negative baseline relationship between the target firm’s innovative capacity and EMNE post-acquisition innovative output is less negative the stronger the EMNE’s knowledge base prior to the acquisition, measured as the patents of the acquirer in the 5 years before the deal plus the number of the cited patents, following Ahuja and Katila (2001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Moderating Role of EMNEs’ Knowledge Base

In terms of the relationship between the output variable and the level of innovation in the region, we found that the EMNE knowledge base is a positive and significant moderator for large enough values of the regional social filter, which measures the degree to which the target region offers an ecosystem favorable to innovation (Rodriguez-Pose and Crescenzi, 2008). As shown in Figure 2, at each level of the social filter, predicted outputs for low-knowledge base EMNEs are lower than the outputs predicted for EMNEs with high knowledge bases.

The Moderating Role of EMNE Knowledge Status

Drawing on the social status theory (Podolny, 1993; Gould, 2002) we contend that EMNE status influences successful integration between the target and acquiring firms in a CBA (Sharkey, 2014). Because our analytical context is that of internationalizing firms, we understand status as reflected by the international press, which we assume to be an important source of signals influencing status considerations by international audiences in the target firm or region. Therefore, we measure status as a standardized residual of a regression with the number of positive news stories about the acquiring EMNE as a dependent variable and a set of firm-level variables as regressors that capture EMNEs’ observable characteristics related to status (e.g. size, innovativeness, profitability, country of origin) (Shen et al., 2014).The intuition is that the uncertainty over the quality of the acquiring EMNEs can make managers wary, not because they are intimidated by the country of origin but rather because information about them may be limited. An Italian manager working for a company recently acquired by a Chinese multinational confirms this point: “Prior to the acquisition we did not know the firm: the acquisition was a bolt from the blue, so we [middle managers] immediately went to see the press . . . to see whether it talked about the firm, but we did not find much . . . of course we knew it was not a bad monster, we had been in China before so we were not scared by Chinese firms, but still there was a great uncertainty there because we did not know much about the firm.”

Insights from our interviews also suggest that skepticism seems to be firm-specific rather than country-specific, while information provided by the media is potentially useful for reducing this uncertainty and creating a more-positive climate for cooperation by reassuring managers at the target firm and in the host location about the quality of the acquiring firm and mitigating fears of being outcompeted as the result of reverse knowledge transfer (Anderson et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2018). We expect that this will have a positive impact on post-acquisition innovation. Our econometric results show the statistical significance of the positive moderating role of high EMNE status, presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Moderating Role of EMNEs’ Status

Conclusions

Our results show that EMNEs do not always benefit from investing in innovative target firms and regions and that acquisitions are not an easy fix for technological laggards. Some time ago, The Economist described EMNEs as “new creatures, bursting out of nowhere to take the world by storm.” We suggest that the extent to which this actually happens largely depends on their firm-specific history of accumulation of knowledge and on their social status and consensus building. Only an elite number of EMNEs can make it; the rest remain stranded, no matter how innovative their target firm or location.

(Vito Amendolagine, Università di Pavia; Elisa Giuliani, Università di Pisa; Arianna Martinelli, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna; Roberta Rabellotti, Università di Pavia e Aalborg University.)

Ahuja G., Katila R. (2001) Technological acquisitions and the innovation performance of acquiring firms: a longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 23:197-220.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/smj.157

Amendolagine, V., Giuliani, E., Martinelli, A., Rabellotti; R. (2018) Chinese and Indian MNEs’ shopping spree in advanced countries. How good is it for their innovative output? Journal of Economic Geography, 18: 1149–1176.

https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/18/5/1149/5123432

Anderson J., Sutherland D., Severe, S. (2015) An event study of home and host country patent generation in Chinese MNEs undertaking strategic asset acquisitions in developed markets. International Business Review, 24: 758-771.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0969593115000244?via%3Dihub

Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., Maskell, P. (2004) Clusters and knowledge: local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28: 31–56.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

Bell, M., Pavitt, K. (1993) Technological accumulation and industrial growth: contrasts between developed and developing countries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 2: 157–210.

https://academic.oup.com/icc/articleabstract/2/2/157/888431?redirectedFrom=PDF

Crescenzi, R., Rodrıguez-Pose, A., Storper, M. (2007) The territorial dynamics of innovation: a Europe–United States comparative analysis. Journal of Economic Geography, 7: 673–709.

https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/7/6/673/960929

Dosi, G. (1988) Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. Journal of Economic Literature, 26: 1120–1171.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2726526?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Fu, X., Hou, J., Liu, X. (2018) Unpacking the relationship between outward direct investment and innovation performance: evidence from Chinese firms. World Development, 102: 111-123.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X17303145?via%3Dihub

Giuliani E. (2007) The selective nature of knowledge networks in clusters: evidence from the wine industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 7: 139-68.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X17303145?via%3Dihub

Gould, R. V. (2002) The origins of status hierarchies: a formal theory and empirical test. The American Journal of Sociology, 107: 1143–1178.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/341744

Hansen, U., Fold, N., Hansen, T. (2016) Upgrading to lead firm position via international acquisition: learning from the global biomass power plant industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 16: 131–153.

https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/16/1/131/2412644

Marin, A., Bell, M. (2006) Technology spillovers from foreign direct investment (FDI): the active role of MNC subsidiaries in Argentina in the 1990s. Journal of Development Studies, 42: 678–697.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220380600682298

Piperopoulos, P., Wu, J., Wang, C. (2018) Outward FDI, location choices and innovation performance of emerging market enterprises. Research Policy, 47: 232–240.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733317301865?via%3Dihub

Podolny, J. M. (1993) A status-based model of market competition. American Journal of Sociology, 98: 829–872.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/230091

Rodriguez-Pose, A., Crescenzi, R. (2008) R&D, spillovers, innovation systems and the genesis of regional growth in Europe. Regional Studies, 42: 51–68.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00343400701654186

Sharkey, A. J. (2014) Categories and organizational status: the role of industry status in the response to organizational deviance. American Journal of Sociology, 119: 1380–1433.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/675385

Shen, R., Tang, Y., Chen, G. (2014) When the role fits: how firm status differentials affect corporate takeovers. Strategic Management Journal, 35: 2012–2030.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/smj.2194

UNCTAD. (2017) World Investment Report. Geneva: UNCTAD.

https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2017_en.pdf

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email