The Impact of Rapid Aging and Pension Reform on Savings and the Labor Supply: the Case of China

Individuals can use savings and labor supply to self-insure against uncertainties over their life cycle, such as idiosyncratic income shocks and changes in longevity and pension benefits. Using China as a case study, we investigate, both empirically and quantitatively, the impact of rapid aging and pension reform on savings and the labor supply, and the roles that savings and the labor supply play as self-insurance channels over the life cycle. Our quantitative results show that rapid aging and pension reforms together contributed to 55% of the increase in the household saving rate in urban China from 1995 to 2009, and they jointly accounted for about 64% of the drastic increase in the labor supply for the same period. Additionally, households’ responses to rapid aging and pension reforms differ across different stages of their life cycle.

Ever since Aiyagari’s groundbreaking heterogeneous agents model (Aiyagari 1994), saving has been recognized as an important instrument that individuals use to self-insure against idiosyncratic income shocks. Another self-insurance instrument, labor supply, has recently gained attention in the literature. Low (2005) shows that allowing flexibility in the number of hours worked in a standard Aiyagari-type heterogeneous agents model brings the life-cycle profile of working hours and life cycle profile of consumption closer to the data. Allowing flexibility in the number of hours worked in the model allows individuals to increase their work hours to react to income shocks, thereby reducing the cost of uncertainty. Pijoan-Mas (2006) also highlights the self-insurance channel of the labor supply and shows that labor supply is at least as important as savings as instruments to insure against income risk.

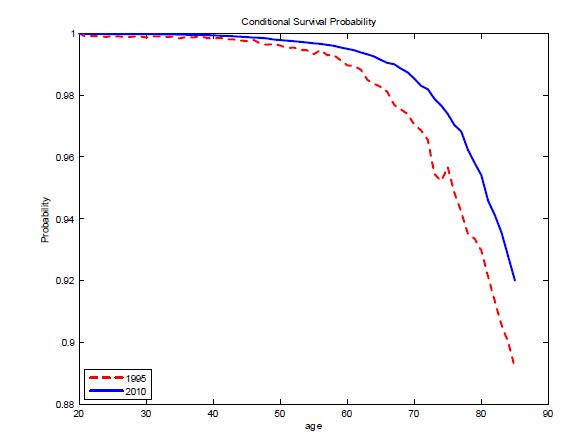

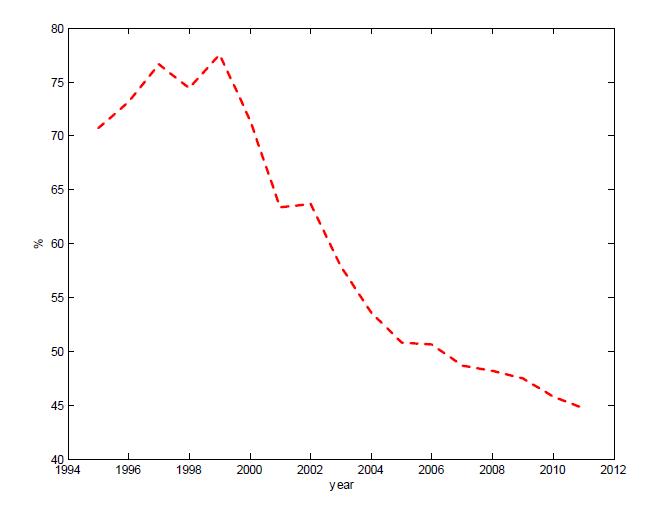

A recent IMF Working Paper (He, Ning, and Zhu 2019) empirically and quantitatively studies the roles that savings and labor supply play as self-insurance channels over the life cycle when an individual faces not only idiosyncratic income risks but changes in longevity and pension benefits as well. We choose China as a case study because China’s population has undergone rapid aging and a large-scale pension reform simultaneously over the past two decades. Therefore, China provides an ideal natural experiment to test the impacts of rapid aging and pension reform on savings and the labor supply, both at the household level and at the aggregate level. Figure 1 shows the dramatic increase in conditional survival probability in urban China from 1995 to 2010: the average life expectancy of Chinese people increased from 68.55 years in 1990 to 74.83 years in 2010. The increase of 6.3 years in life expectancy over twenty years is far more significant than that experienced in other major countries. Meanwhile, after two major reforms, the Chinese pension system significantly reduced its benefits from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: Chinese Census 1995 and 2010

Source: Chinese Statistics Yearbook. The replacement ratio is calculated by dividing the current year’s social security benefits per retiree by the current year’s wage income per worker.

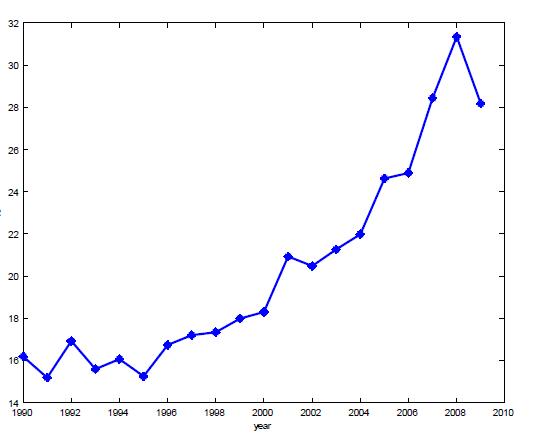

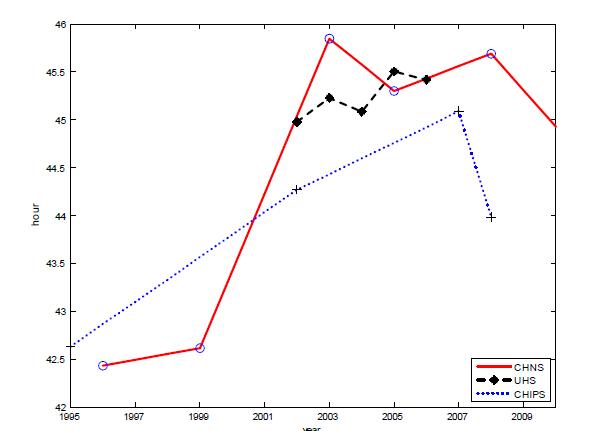

What was the reaction to those changes? Because they expect to live longer than earlier cohorts but receive lower pension benefits when they retire, urban Chinese households need to prepare for their old age consumption by either increasing savings or working longer hours to accumulate more savings before retirement. Both reactions show up in the micro-level household survey data, as shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. He, Ning, and Zhu (2019) conduct a difference-in-differences analysis based on data from the Chinese Household Income Project Survey (CHIPS), using 2005 pension reform as an exogenous change. The results confirm that a pension reform aiming to reduce the replacement ratio could lead to a higher saving rate and longer working hours among households.

Source: Urban Household Survey

Source: Urban Household Survey, Chinese Household Income Project Survey, and China Health and Nutrition Survey. Sample only includes males aged 18 to 60 and females aged 18 to 55.

He, Ning, and Zhu (2019) further provide a connection among the four Figures by setting up a large-scale (70-period) heterogeneous agent overlapping generations general equilibrium model. In the model, an individual faces stochastic income risks up to retirement and faces longevity risks through the whole life cycle. She has to make decisions on consumption, asset holding, and labor supply. The main features of the Chinese pension system are also captured in the model. We calibrate the model to match the Chinese economy before the pension reform and rapid aging occurred by using data from micro-level Chinese household surveys. We then input the exogenous demographic change (as shown in Figure 1) and the policy changes in the pension system (as shown in Figure 2) into the model. We solve the model along a transition path to investigate the short-run impact of the pension reforms and rapid aging on variables of interest for the period 1995–2009.

Our quantitative results show that the rapid aging and the pension reforms together contributed to 55% of the increase in the household saving rate in urban China from 1995 to 2009 (data shown in Figure 3), and they jointly capture about 64% of the drastic increase in the labor supply for the same period (data shown in Figure 4). The exercise shows that the impact of the demographic change and the pension reform on the aggregate household saving rate and labor supply in urban China is quite pronounced.

Further decomposition exercises demonstrate that the associated changes in pension benefits due to the pension reforms alone contribute to about 40.6% of the increase in the household saving rate and 41% of the increase in the labor supply over this period. At the same time, the rapid aging contributes more to the increase of the labor supply than to the saving rate. It alone contributes to about 36% of the increase in the labor supply but only 11% of the increase in the household saving rate over that period. Pension reform is more important in explaining the rising saving rate and labor supply than rapid aging. Notice that the sum of the impacts from the pension reforms and rapid aging on labor supply (77%) is significantly higher than the contribution of the pension reforms and rapid aging to labor supply jointly (64%). The reason is that increasing labor supply in response to rapid aging would increase workers’ labor income. However, workers’ social security benefits partly depend on their life cycle average labor income. Therefore, increasing labor supply due to rapid aging would partly offset the impact of the pension reforms on labor supply.

Looking at the life-cycle, the quantitative exercises indicate that the motive to save more due to concerns about pension reforms increases after age 40 and peaks at age 59, right before retirement age because at this stage, individuals could have more income available to save. However, after retirement at age 60, the increase in the saving rate is mostly driven by the change in household saving behavior as a response to rapid aging because pension benefits are already set, but individuals still face longevity risks. On the other hand, the labor supply response of households also has a life cycle pattern. When households increase labor supply in their 30s, it is mostly in response to longevity risks. After age 40, they work harder mostly due to the concern that pension benefits will be reduced given that working longer hours at later ages contributes more to higher labor income than at earlier ages since the base wage increases with age, and higher labor income would raise pension benefits according to the benefit formula. Overall, households’ savings and labor supply behaviors do respond to aging and pension reforms differently at different stages of their life cycle.

Academics, the public, and policymakers have undertaken a heated debate about the drivers of the high Chinese saving rate (see VoxChina columns on September 13, 2017, September 5, 2018, and April 17, 2019). The study outlined here contributes to this debate by bringing pension reforms to the fore. Looking forward, the findings suggest that the recent effort by the Chinese government to improve social security portability and reduce the urban-rural divide could help reduce households’ precautionary savings undertaken due to the lack of pension coverage and in turn, reduce the national saving rate.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

[Hui He, International Monetary Fund and Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance (SAIF), China; Lei Ning, Institute for Advanced Research, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics (SUFE), China; Dongming Zhu, School of Economics and Key Laboratory of Mathematical Economics, SUFE, China.]

Aiyagari, S. (1994). “Uninsured Idiosyncratic Risk and Aggregate Saving,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 659–684. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118417

He, H., L. Ning and D. Zhu (2019). “The Impact of Rapid Aging and Pension Reform on Savings and the Labor Supply: The Case of China,” IMF Working Paper 19/61, International Monetary Fund. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3370957

Low, H. W. (2005). “Self-Insurance in a Life-cycle Model of Labour Supply and Savings,” Review of Economic Dynamics, 8, 945–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2005.03.002

Pijoan-Mas, J. (2006). “Precautionary Savings or Working Longer Hours?” Review of Economic Dynamics, 9, 326--352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2005.11.002

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email