Taxation Trends and Challenges in a Digital Economy — Implications for the People’s Republic of China

The digital economy is growing rapidly across the globe and, among developing countries, the PRC is a leader. Despite its promise, the global digital economy also poses many challenges, including tax base erosion and profit shifting. Given the initial efforts by the PRC to address these challenges, this post recommends that the country continues to participate in the international taxation forum, adopt unilateral measures, improve its tax registration system, and strengthen its tax administration capacity.

The digital economy is growing rapidly across the globe. The 2018 Digital Economy and Society Index (see Note 1) shows that New Zealand, Iceland, and the Republic of Korea are the best performers in adopting digital technology in economic and social activities, while some developing countries, such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC), are rapidly catching up.

Nonetheless, the global digital economy also poses many challenges. Among these are tax base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). While BEPS has been discussed intensively at a global level, solutions are yet to emerge. Key features of a digital economy can exacerbate the risks of BEPS. These features include mobility, reliance on data, network effects, spread of multisided business models, a tendency toward monopoly or oligopoly, and volatility (BEPS Action 1 in OECD, 2015). Conventional taxation systems often rely on “physical presence” for brick-and-mortar companies and are irrelevant in the context of a digital economy.Trend of the Digital Economy in the People’s Republic of China

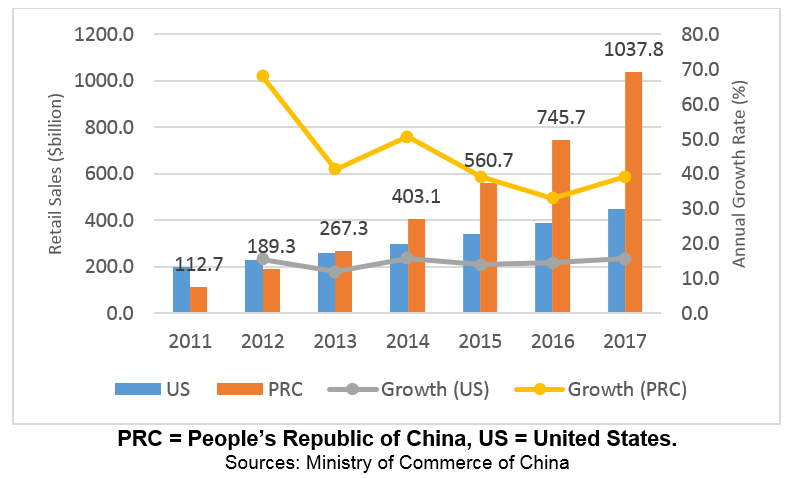

In 2017, the PRC was the largest market for e-commerce retail sales. Sales figures were more than double those of the United States and were nearly 10 times higher than in 2011 (Figure 1). When considering mobile payments, both the number of users and the amount of transactions are the highest in the world — and growing fast. The PRC’s cross-border e-commerce has also been increasing steadily. Furthermore, the PRC is also in the top three global destinations for venture capital investments in key technologies, including fintech, autonomous driving, 3-D printing, and artificial intelligence (McKinsey Global Institute, 2017).

PRC = People’s Republic of China, US = United States.

Sources: Ministry of Commerce of China, http://dzsws.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/ndbg/201805/20180502750562.shtml. U.S. Bureau of the Census. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ECOMSA.

The PRC’s “big four” companies — JD.com, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent (BAT) — are now among the ten largest companies in the world in terms of market capitalization. The total market capitalization serving consumers exceeded $1 trillion in 2016, suggesting that the PRC is already a global leader in e-commerce and digital payments. Dominant players vary depending on the types of transactions.

In recent years, the business-to-customer (B2C) market has taken a more prominent role in the PRC’s e-commerce sector. This trend reflects the PRC’s accommodative policies and changing consumer preferences. B2C e-commerce sales more than doubled in the PRC from 2012 to 2016, which may be due to the development of e-commerce platforms that allow individuals to easily register as business establishments that sell goods. (Terada-Hagiwara, Gonzales, and Wang, 2019)

In urban areas, cashless payments are becoming the norm through platforms such as Tencent Holdings' WeChat and Alibaba Group Holding's Alipay. However, there is an urban–rural divide: internet users are still limited in rural areas. Urban internet users reached 563 million by December 2017, compared to only 209 million users in rural areas. In regions such as Beijing, Guangdong, and Shanghai, usage grew strongly, while provinces such as Guizhou, Tibet, and Yunnan have lagged behind (Herrero and Xu, 2018).

Measures for the Digital Economy and Implications for the PRC

From the perspective of countering BEPS, suggested measures for the digital economy cannot be differentiated from other measures since the digitalization of the economy does not raise unique BEPS issues. Therefore, measures such as the revision of transfer pricing rules, the modification of permanent establishments, and controlled foreign corporation rules all need to be evaluated in order to address the challenges posed by a digital economy. For the broader challenges of nexus, data, and income characterization, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has suggested a new concept of “significant economic presence” as an alternative to current permanent establishment rules. OECD has also suggested a withholding tax on digital transactions and the introduction of an “equalization levy” (BEPS Action 1 in OECD, 2015).

For cross-border transactions, the OECD (2018) reports that 110 economies have agreed to form an international consensus by 2020 on how to tax digital businesses across borders. These economies have agreed to review the old or traditional tax systems that do not fit the digital economy. While these suggested options are good starting points toward an international standard for taxing the digital economy, the details are yet to be developed and finalized.

In the meantime, various countries have taken unilateral measures. These are not coordinated and they vary in content and timetable; however, they share the following aspects: 1) They are designed to be implemented through domestic or regional laws, rather than rely on international cooperation; 2) They aim to preserve or expand the source taxation of online business activities generally performed by multinational entities; and 3) They draw upon certain elements of the above options originally proposed by OECD for international standards(see Note 2).

In Asia, some countries such as India, Malaysia, and the Philippines have taken measures to broaden the scope of their withholding tax or introduce new turnover taxes. However, the major tool used to respond to the development of the digital economy is by instituting value added tax (VAT). For example, economies in Southeast Asia acknowledge the importance of e-commerce taxation in order to take advantage of growth and level the playing field between online businesses and those that operate offline. However, their actions have been mostly limited to imposing VAT on various transactions.

For the PRC, Terada-Hagiwara, Gonzales, and Wang (2019) identify four areas for policy actions. They are: 1) Continued participation in the International Taxation Forum; 2) Adoption of unilateral measures; 3) Improvement of the tax registration system to address untaxed consumer-to-consumer transactions; and 4) Strengthening and increasing the capacity of the tax administration. On the third point, the PRC is one of the few countries to apply VAT to most financial services and real estate transactions. Nonetheless, issues remain — such as achieving the right balance in the efficiency and effectiveness of tax collection. For example, the PRC eliminated the VAT-exempt threshold for cross-border e-commerce imports in 2016, which means that small transactions are taxed even when the tax revenue falls below the cost of collection. This leads to the potential of additional research.

Note 1: The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) is a composite index and presents the weighted average of five main dimensions, namely, connectivity, human capital, internet use, integration of digital technology, and digital public services. The DESI summarizes relevant indicators on digital performance and tracks the evolution of digital competitiveness (see https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/desi).

Note 2: The OECD–G20 BEPS Interim Report 2018 (OECD 2018) also includes a fourth group, “Specific regimes targeting large multinational enterprises.” This policy brief excludes it because the regimes are not specific to digitalization even though broadly relevant.

(Akiko Terada-Hagiwara, Principal Economist at the Office of the Director General of East Asia Department, Asian Development Bank.)

European Commission. The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/desi.

Herrero, A. G., and J. W. Xu. 2018. “How Big is China’s Digital Economy?” Bruegel Working Paper No. 04.

Law, S. B. 2010. “Technical Services Fees in Recent Tax Treaties.” Bulletin of International Taxation 64:5. IBFD.

McKinsey Global Institute. 2017. “Digital China: Powering the Economy to Global Competitiveness.” https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Featured%20Insights/China/Digital%20China%20Powering%20the%20economy%20to%20global%20competitiveness/MGI-Digital-China-Report-December-20-2017.ashx.

Ministry of Commerce of China. 2017. “Report of E-Commerce in China.” Beijing. http://dzsws.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/ndbg/201805/20180502750562.shtml.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2015 Final Reports. Paris: OECD Publishing.

———. 2017. “Going Digital.” http://www.oecd.org/going-digital/project/.———. 2018. Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation. Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Taxamo. https://blog.taxamo.com/insights/malaysia-digital-tax-annoucement.

Terada-Hagiwara, A., K. Gonzales, and J. Wang. 2019. “Taxation Challenges in a Digital Economy — The Case of the People's Republic of China.” Asian Development Bank Brief Series No.108., Manila.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ECOMSA.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email