Income Inequality among Old Chinese

Using data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) from 1991–2015, we decompose the income inequality among old Chinese and compare the income inequality between old households and young households. We develop an OLG model and a new empirical method to test how initial socioeconomic differences transmit to income inequality in the working years and then in old age. We find that the urban-rural gap and educational differences are the two most important factors leading to income inequality among the old. We also find that income inequality accumulates with age in China and is reinforced in old age by the fragmented Chinese public pension system.

China is greying, and its large old population is growing rapidly. Meanwhile, income inequality is also growing in China: the income share held by the top 10% increased from 26% to 40% between 1980 and 2015 (Alvaredo et al., 2017). These two trends motivate us to study income inequality among old Chinese (aged 60 and above). We compare the income inequality among the old and the young and study the factors causing old-age inequality. Our study aims to document the transmission process leading to old-age inequality and to inform public policies targeted at reducing the income inequality among the old.

There are different views in the literature about how income inequality evolves from the working years to old age. The first view is that income inequality among the old is greater than the inequality among the young because disadvantages and advantages accumulate over the lifecycle (Deaton and Paxson, 1994). The second view is that income inequality among the old should be less than that of the young because of redistribution within the public pension system (Deaton et al., 2002). A third view points out that income inequality remains stable over the lifecycle because the two opposite effects of accumulated income inequality and redistribution via pensions offset each other. The empirical literature mainly finds that income inequality of the old is higher that of the young (e.g., Deaton and Paxson, 1994, for the U.S., U.K., and Taiwan; Chen et al., 2018, for mainland China). However, there is limited research modeling or estimating the transmission process of income inequality over the lifecycle. In our recent study, Hanewald et al. (2019), we show that income inequality in China is caused by the urban-rural gap and mediated by educational inequality due to unequal distribution of public resources between rural and urban areas. Moreover, we document that the fragmented public pension system in China reinforces income inequality among old households compared to that among young households.

Hanewald et al. (2019) first develop a stylized theoretical model to analyze how the urban-rural gap and educational inequality transmit to income inequality during the working years and in old age. The model is a three-period overlapping generation model in which individuals consume, save, work, invest in education and assets, make transfers to their children, and participate in a pay-as-you-go pension system. Assuming a developing economy with a lower quality of education and less-developed financial markets in rural areas, we derive two hypotheses from the theoretical model: (i) income inequality is greater in old age than that during working years, and (ii) income inequality during the working years and old age is driven by the educational differences between urban and rural areas. To decompose income inequality into its contributors and to test the transmission process of income inequality, we develop a new empirical method combining the regression-based inequality decomposition method (Morduch and Sicular, 2002; Wan, 2004) and the three-step mediating effect test (Baron and Kenny, 1986).

Trends in income inequality for old and young households

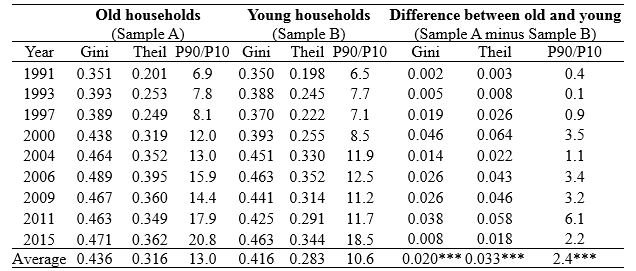

Using data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), Hanewald et al. (2019) compare the income inequality for different age groups in each survey year between 1991 and 2015. The dataset covers nine provinces that vary substantially in terms of geography, economic development, and other socioeconomic factors and provide a good representation of China (Chamon et al. 2013). We consider two subsamples: old households (with at least one member aged 60 or older) and young households (with only young members). As shown in Table 1, three measures of inequality [the Gini coefficient, the Theil index, and the P90/P10 ratio (see Note 1)] all show that income inequality among old households was higher than that among young households in each survey year. This result supports our hypothesis that income inequality is larger among the old than among the young.

Source: Hanewald et al. (2019)

Decomposition of income inequality by socioeconomic characteristics

To understand the causes of income inequality, we use a regression-based approach to decompose income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) among old households into its socioeconomic determinants in each survey year between 1991 and 2015. To apply this method, we first regress income on key socioeconomic factors. Using the estimated coefficients in this regression, we calculate the contribution of each socioeconomic factor to the Gini coefficient of income. We find that the urban-rural gap and educational inequality contribute most to old-age income inequality (14.2% in total in 2015). Moreover, we find that about one-third to one-half of the urban-rural gap contribution to income inequality is mediated by education.

Decomposition of income inequality by income components

To further investigate how the urban-rural gap and education contribute to income inequality through different income components, we decompose income inequality by income components in each survey year between 1991 and 2015. We find that pensions are more unequally distributed than total household income per capita. Furthermore, since 2004, pensions have contributed most to income inequality among old households. This result indicates that there is limited redistribution in the fragmented public pension system in China.

Inequality decomposition for old households and young households

We also compare the results of the income inequality decomposition between old households and young households. We find that the contributions of the urban-rural gap and education to income inequality are all larger among old households than among young households. This indicates that the inequality caused by the urban-rural gap and education accumulates over the lifecycle, leading to greater income inequality among old households. We also find that in recent years, income from work has contributed the most among young households, while pensions have contributed the most to income inequality among old households. This result indicates that the fragmented public pension system in China leads to greater income inequality among old households.

Longitudinal analysis and the role of the fragmented pension system

In addition to the cross-sectional analysis in each survey year, we follow one cohort of households who were young in 2000 and old in 2015, to identify their transmission process of income inequality. The longitudinal analysis excludes potential cohort effects and minimizes the impact of uncontrollable household heterogeneity on income inequality. It also allows us to track one’s occupational sector and to document the direct evidence on the role of the fragmented pension system. The results confirm both hypotheses. The results show that pension inequality explains almost all of the inequality increase from 2000 to 2015 for the examined household cohort. The results also confirm that old-age income inequality is reinforced by the pension system, which is fragmented by occupational sector.

Conclusion

Hanewald et al. (2019) show that income inequality among the old is greater than that among the young in China. This is due to a transmission process leading to income inequality: the urban-rural gap and educational inequality lead to income inequality during the working years which translates into pension inequality that reinforces income inequality in old age. Our finding is robust across cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses.

Our findings have several important policy implications. China’s public pension system is fragmented. Future pension reforms should improve equality across different pension programs and improve the redistribution effect of the public pension system. Moreover, public policy should mitigate the urban-rural educational difference, which can further reduce income inequality in the long run. For example, China should improve the welfare of rural migrants in urban areas and provide them with education opportunity equal to urban residents.

Note 1: The Gini coefficient and the Theil index are the two most commonly used measures of income inequality. For both the Gini coefficient and the Theil index, a value of one (or 100%) indicates maximum inequality while zero represents perfect equality where everyone has the same income. The P90/P10 ratio is the ratio between the 90th and the 10th quantile percentile of the income distribution. A higher P90/P10 ratio indicates higher inequality.

(Katja Hanewald is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Risk and Actuarial Studies; Ruo Jia is an Assistant Professor and Senior Research Scientist in the Department of Risk Management and Insurance, School of Economics, Peking University; Zining Liu is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Risk Management and Insurance, School of Economics, Peking University.)

References

Alvaredo, F., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., and Zucman, G. (2017). Global inequality dynamics: New findings from WID.world. American Economic Review, 107(5), 404–409.

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Chamon, M., Liu, K., and Prasad, E. (2013). Income uncertainty and household savings in China. Journal of Development Economics, 105, 164–177.

Chen, X., Huang, B., and Li, S. (2018). Population ageing and inequality: Evidence from China. The World Economy, 41(8): 1976–2000.

Deaton, A. Gourinchas, P., and Paxson, C. (2002). Social security and inequality over the life cycle, in The Distributional Effects of Social Security Reform, Feldstein and Liebman (eds.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Deaton, A., and Paxson, C. (1994). Intertemporal choice and inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 102(3), 437–467.

Hanewald, K., Jia, R., and Liu, Z. (2019). Why is inequality higher among the old? Evidence from China. ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR) Working Paper No. 2019/10. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3436586

Liu, Z. (2005). Institution and inequality: The hukou system in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 33(1), 133-157.

Morduch, J., and Sicular, T. (2002). Rethinking inequality decomposition, with evidence from rural China. The Economic Journal, 112(476), 93-106.

Wan, G. (2004). Accounting for income inequality in rural China: A regression-based approach. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32(2), 348-363.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email