What Happens to Rural Labor Supply Following the Birth of a Son or a Daughter?

Our research shows that rural Chinese women's labor supply falls for one year following the birth of a daughter before returning to pre-birth levels while the negative impact of a son on women's labor supply is larger and persists for four years. Furthermore, there is a decrease in household cigarette consumption, and an increase in the mother's probability of being in school, her leisure time, and her participation in decision-making following the birth of boys relative to daughters. These results are consistent with the idea that mothers are rewarded for giving birth to boys, leading them to have more leisure and work less.

Female labor force participation is considered an important marker for human development. Much of the economics literature focuses on policies and developments that increase female labor force participation (Jensen 2012; Heath and Mobarak 2015; Goldin and Katz 2000, 2002; Bailey 2006). However, data show declines in female labor force participation over periods of positive economic growth in countries such as India (Afridi, Dinkelman and Mahajan 2018; Fletcher, Pande and Moore 2017) and China (Wang 2019).

In recent research (Wang 2019), I examine how the birth of a son versus a daughter affects the labor force participation of women and men in rural China. This research question is important for policy given recent fertility changes in China. An unintended consequence of changing fertility is that the sex ratio at birth changes. My research shows that the sex of the child can have large effects on the labor market outcomes of women.In the context I study, most households work in family-run agriculture. Therefore, any impact of birth on labor supply decisions is not about rigidities in formal sector jobs or labor market discrimination on the part of employers. Rather, changes in labor supply in this context tell us about the preferences of the households themselves.

I use a data set that follows the same household for many years, which allows me to look at the same person before and after the arrival of a child. Then I examine outcomes before and after the arrival of a son as compared to the arrival of a daughter.

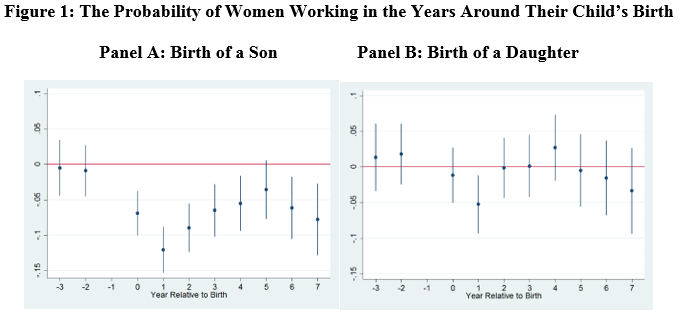

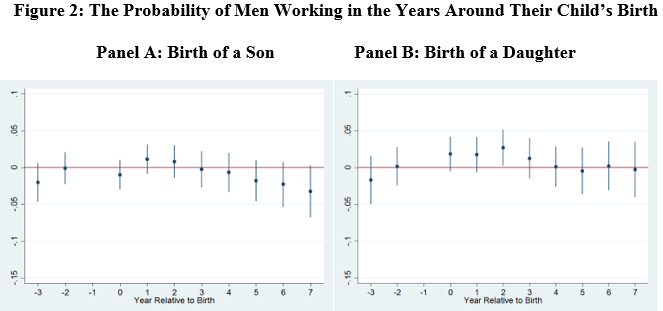

I find that women’s labor supply falls by about 5 percent for one year following the birth of a daughter (Panel B of Figure 1) before returning to pre-birth levels. The negative impact of a son on women’s labor supply (Panel A of Figure 1) is much larger than for a daughter and persists for five years. There are no corresponding declines in the labor supply of men immediately after the birth of either a son or a daughter (Figure 2).

Notes: The dots are coefficient estimates from a regression where the coefficients are relative to the year immediately prior to the year of birth. The lines give the 95% confidence interval. The regressions include fixed effects for household and year and the estimates are clustered at the household level. The sample size is 20,131.

The next question I address is why we see this sex-specific pattern for women. There are many possible explanations. For example, families may think there are higher returns to investment in boys than in girls, perhaps due to differences in labor market outcomes for men and women. In such a scenario, women may drop out of the labor force to spend quality time with their sons in their early years.

I look at other results that help shed light on which best explains the labor supply responses to boys and girls. I find the following results for the birth of sons relative to daughters: a decrease in household cigarette consumption, an increase in the probability that a school-age mother remains in school, an increase in her leisure time, and an increase in her participation in decision-making over household durable goods purchases. I also look at whether there are any increases in other investments in sons versus daughters, including breastfeeding and immunizations, but find no differences in these outcomes by the sex of the child.

Given these results, it does not seem to be the case that the story is about investing more in sons than in daughters, because households are not making other complementary investments that I can measure in breastfeeding and immunizations. The best explanation is that women are rewarded for having boys in rural China. Thus, women get more leisure time and work less in the field. Women in general tend to dislike smoking so the household reduces their smoking after women give birth to sons.

The estimates of this research suggest that there is a potential link between patterns in the sex ratio in China and female labor force participation over time. Thus, any policies that affect the sex ratio, such as changes in fines associated with additional children, may have unintended consequences on female labor force participation.

(Shing-Yi Wang is an Associate Professor of Business Economics and Public Policy at Wharton.)

References

Afridi, F., Dinkelman, T., & Mahajan, K. (2018). Why are Fewer Married Women Joining the Work Force in Rural India? A Decomposition Analysis over Two Decades. Journal of Population Economics, 31(3), 783–818.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00148-017-0671-y

Bailey, M. J. (2006). More Power to the Pill: The Impact of Contraceptive Freedom on Women’s Life Cycle Labor Supply. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(1), 289–320.https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/121/1/289/1849021

Fletcher, E., Pande, R., & Moore, C. M. T. (2017). Women and Work in India: Descriptive Evidence and a Review of Potential Policies. SSRN Electronic Journal.Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2002). The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage Decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 110(4), 730–770.

https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/2624453/goldin_powerpill.pdf?sequence=4

Heath, R., & Mushfiq Mobarak, A. (2015). Manufacturing Growth and the Lives of Bangladeshi Women. Journal of Development Economics, 115, 1–15.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304387815000085

Jensen, R. (2012). Do Labor Market Opportunities Affect Young Women’s Work and Family Decisions? Experimental Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2), 753–792.Wang, S. Y. (2019). The Labor Supply Consequences of Having a Boy in China (No. w26185). National Bureau of Economic Research.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w26185.pdf

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email