Primary Care Chronic Disease Management in Rural China

Dec 11, 2019

Health systems globally face increasing morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases, yet many — especially in low- and middle-income countries — lack strong primary care. Among recent contributions to understanding how economic incentives can be harnessed to address this challenge is a study in which we analyze China’s efforts to promote primary care management for rural residents with chronic disease. Utilizing unique panel data and the plausibly exogenous variation in management intensity generated by administrative and geographic boundaries, we find that villagers with hypertension or diabetes residing in a township with more intensive primary care management have more primary care visits and better medication adherence with fewer specialist visits and hospitalizations. The resource savings from avoided inpatient admissions more than offset the costs of the program.

Low- and middle-income countries face increasing morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases. Globally, noncommunicable chronic diseases (NCDs) account for about two-thirds of deaths and this increasing burden of morbidity that reduces productivity, increases medical spending, and shortens lives (Bloom et al. 2012).

China is no exception. Indeed, given its aging population and relative success in controlling infectious disease, NCDs have long been the primary cause of ill health and premature death in China (Yang et al. 2008). Additionally, NCDs loom large in the policy goals for Healthy China 2030 and in efforts to harness AI and other new technologies for improving health. Evidence suggests widespread under-diagnosis and poor management of prevalent conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, especially in rural areas (Yang et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017). For example, high blood pressure was already the leading preventable risk factor for premature mortality in China in 2005 (He et al., 2009). China is also home to about one-quarter of the world’s population with diabetes, half or more of whom are undiagnosed (Zhao et al., 2016). Although the prevalence of diabetes increases with age and urbanization, but mortality rates are higher for rural Chinese (Bragg et al., 2017).

These factors underscore the need for strong primary care. Yet China, like many low- and middle- income countries, lacks adequate primary care resources both in terms of numbers and quality. Patients benefiting from China’s universal health coverage flock to hospital outpatient departments instead. As Professor Meng Qingyue and colleagues emphasize, “from 2005 to 2015, the proportion of healthcare services provided by primary care decreased by 7 percent” despite efforts to strengthen primary care, in part because “in 2010, [only] 5.6 percent of the doctors in township health centers had a formal medical education” (five years of medical school). This percentage has increased to only 10 percent in 2017 (Meng et al., 2019). China’s hospital-based healthcare system suffers from other inefficiencies as well (Zhang et al., 2017; Hu, 2019), including clear evidence that even well-qualified physicians do not have incentives always aligned with the best interests of patients (Currie et al., 2014).

Facing these challenges, the Chinese government has recognized this pressing issue and indeed has set a high priority on strengthening primary care services and providing public chronic disease management services during the past ten years of healthcare reform in China (Hu, 2019; Meng et al., 2019). For example, China’s Equalization of Basic Public Health Services (EBPHS) policy has started to provide more basic public health services and programs since 2009, including establishing health records for all citizens and launching community-level programs for monitoring and managing individuals suffering from hypertension and diabetes. These services are delivered by primary healthcare organizations and are free to the patient at the point of use. They are funded jointly by the central and local government, with a minimum funding for the basic package of ¥15 (£1.70; €2; $2) per person in 2009 and ¥55 in 2017 (Yuan et al., 2010).

Unfortunately, there is not yet much rigorous evidence about the impact of improving primary care in China. To help fill this gap, in a recent study (Chen et al., 2019), we analyze the impact of a program that gives primary care physicians financial and reputational incentives to identify patients and enroll them in primary care management for their conditions. Specifically, our paper analyzes the effect of this policy in Tongxiang, China, which is a mostly rural county in Zhejiang province. Teaming up with researchers at the Zhejiang and Tongxiang Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we assemble a unique dataset linking administrative and health data between 2011 and 2015 at the individual level for all of the more than 70,000 rural Chinese patients diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes by the end of 2015.

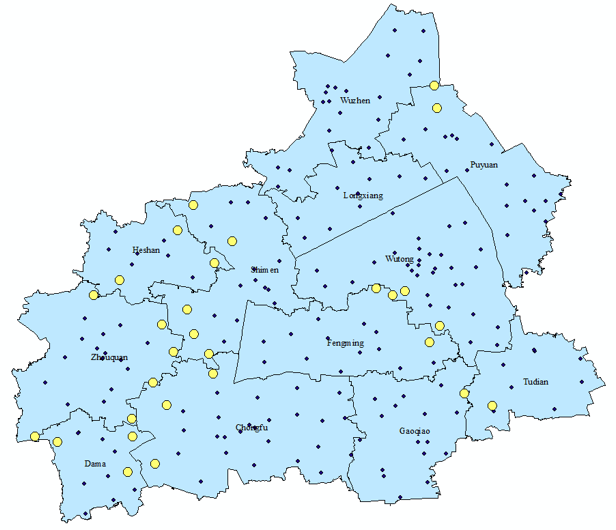

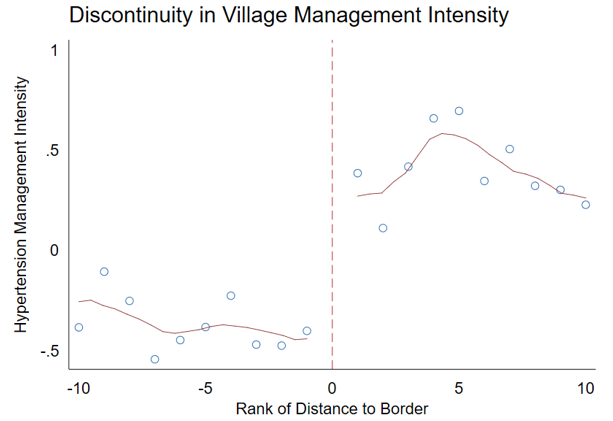

Our research strategy utilizes variation in management intensity generated by administrative and geographic boundaries to study the program’s effects. We focus on nearby villages that are within two kilometers of each other, but have primary care services managed by different townships (see Figure 1). The 14 pairs of boundary villages are similar across population characteristics such as age, gender, and educational attainment, and their residents enjoy identical insurance coverage and hospital access; but as shown in Figure 2, they differ in intensity of primary care management (partially explained by the pre-existing stock of primary care physicians in each township).

Figure 1: Illustration of Neighboring Villages

Figure 2. Illustrating the Study Design: Discontinuity of Village-level Hypertension Management Intensity, by Distance to Township Boundary

The stock of physicians before the reform was determined by higher-level officials as part of China’s rather rigid “headcount quota system” for all public service units. According to a 2016 report by the World Bank, World Health Organization, and three PRC ministries (of finance, health, and human resources), “by introducing rigidities and inefficiencies in the recruitment and management of health workers and limiting the mobility of health professionals, such a system distorts the labor market and compromises its ability to deliver quality healthcare services,” especially for rural primary care (see Note 1). Townships can hire temporary workers outside of the quota system, which is one response they undertook to leverage the pre-existing stock of physicians to scale up outreach and services with the funding and incentives under the program.

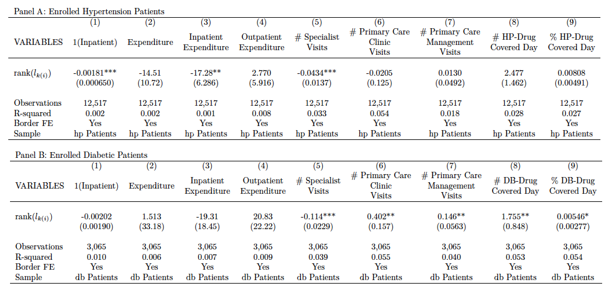

We utilize this plausibly exogenous variation to compare patients of neighboring villages in different townships. The regression results in Table 1 show how a different management intensity affects healthcare utilization (within a village-pair). The key explanatory variable, rank (the higher the better), captures the management intensity of disease d in township k for patient i. We find that patients residing in a village within a township with more intensive primary care management, compared to neighbors with less intensive management, had more primary care visits, fewer specialist visits, fewer hospital admissions, and lower inpatient spending in 2015 (see Table 1). For example, a greater primary care management intensity (proxied by the difference between the most- and least-intensely managed townships in our data) reduces the probability of hospitalization by 13 percent (a 0.018 percentage point lower likelihood of a hospital admission, from a base hospitalization rate of 0.14) for residents suffering from hypertension. These results suggest that primary care chronic-disease management reduces avoidable hospital admissions for ambulatory-care sensitive conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, indicating better health outcomes in terms of chronic disease control.

No such effects are evident in 2011, shortly after the launch of the program (2009). This suggests that the chronic disease management component of the EBPHS policy started to show its effectiveness a few years after its launch and baseline differences probably do not explain different program effects across villages.

We re-run our main analysis (Table 1) with controls on the number of physicians at baseline and find that our results are stable to this robustness check. We also find that reputational incentives from the rankings of primary care management of each township perhaps promote management intensity.

Exploring the mechanism for reduced specialist and hospital utilization, we find that patients with more intensive primary care management exhibit better drug adherence as measured by medication-in-possession (e.g., the number of days in which the patient had a filled anti-hypertensive prescription in 2015). As shown in Columns 8 and 9 of Table 1, comparing the townships that are ranked first and last, the difference in the number of days in possession of an anti-hypertensive drug is about 25 days, which is 29 percent of the average. For anti-diabetic medication, the difference is 14 percent of the average anti-diabetic drug possession days. These empirical results suggest that a higher-intensity management by village doctors may significantly increase medication adherence among patients. This finding is important, given substantial evidence that drug adherence is crucial for preventing complications from chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes and narrowing disparities in health outcomes (Conn et al., 2016; Simeonova, 2013; Wong et al., 2014; Yue et al., 2014).

Note 1: See page 89 in the chapter, “Strengthening Health Workforce for People-centered Integrated Care,” in the World Bank and Government of China report: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/24720/HealthReformInChina.pdf.

Note 2: The policy may have enhanced other aspects of population health such as screenings, risk factor surveillance, and health education. However, since we only have data for those with hypertension and diabetes, those other aspects fall outside the scope of our data and analysis. Certainly, as noted above, China has ambitious plans for enhancing the strength of primary care to attract residents to first-contact care in communities rather than hospitals, as well as goals for enhancing healthy life expectancy as part of the Healthy China 2030 plan and the national demonstration areas for the NCD management program. Future research aims to assess the impact of those broader initiatives for controlling NCDs.

(Yiwei Chen, Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Hui Ding, Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Min Yu, Zhejiang Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Hangzhou, China; Jieming Zhong, Department of NCD Control and Prevention, Zhejiang CDC, Hangzhou, China; Ruying Hu, Department of NCD Control and Prevention, Zhejiang CDC, Hangzhou, China; Xiangyu Chen, Department of NCD Control and Prevention, Zhejiang CDC, Hangzhou, China; Chunmei Wang, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Tongxiang, China; Kaixu Xie, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Tongxiang, China; Karen Eggleston, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.)

References

Bloom, D. E., E. Cafiero, E. Jané-Llopis, S. Abrahams-Gessel, L. R. Bloom, S. Fathima, and D. O’Farrell, “The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases.” Working Paper No. 8712. Program on the Global Demography of Aging, 2012. URL: https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1288/2013/10/PGDA_WP_87.pdfBragg, F., M. V. Holmes, A. Iona, Y. Guo, H. Du, Y. Chen, Z. Bian, L. Yang, W. Herrington, D. Bennett, and I. Turnbull, “Association Between Diabetes and Cause-specific Mortality in Rural and Urban Areas of China,” Jama, 317:3 (January 2017): 280-289. URL: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2598266

Chen, Y., H. Ding, M. Yu, J. Zhong, R. Hu, X. Chen, C. Wang, K. Xie, and K. Eggleston, “The Effects of Primary Care Chronic-Disease Management in Rural China,” National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2019. URL: https://siepr.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/wp1050.pdf

Conn, V. S., T. M. Ruppar, M. E. Rn, and P. S. Cooper, “Patient-centered Outcomes of Medication Adherence Interventions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Value in Health 19:2 (2016): 277-85. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2015.12.001. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4812829/

Currie, J., W. Lin, and J. Meng, “Addressing Antibiotic Abuse in China: An Experimental Audit Study,” Journal of Development Economics 1 (September 2014): 39-51. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4776334/pdf/nihms761400.pdf

Lu, J., Y. Lu, X. Wang, X. Li, G. C. Linderman, C. Wu, and M. Su, “Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in China: Data from 1.7 million Adults in a Population-based Screening Study,” China PEACE Million Persons Project, Lancet 390 (2017): 2549-2558. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29102084

He, J., Gu, D., Chen, J., Wu, X., Kelly, T. N., Huang, J., and Klag, M. J., “Premature Deaths Attributable to Blood Pressure in China: A Prospective Cohort Study,” Lancet 374:9703 (2009): 1765–1772. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19811816

Hu, S., “Review and Expectation of New Healthcare Reform in China: Strategies, Role of Government, Market, and Incentives,” Soft Science of Health 33:9 (2009): 3-6.

Meng, Q., A. Mills, L. Wang, and Q. Han, “What Can We Learn from China’s Health System Reform?”, BMJ 365 (June 19, 2019): 12349. URL: https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l2349.long

Ministry of Health, “Chinese Health Statistical Yearbook 2011,” Peking Union Medical College Press, 2012.

Simeonova, Emilia, “Doctors, Patients, and the Racial Mortality Gap,” Journal of Health Economics 32:5 (2013): 895-908. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.07.002. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23933996

Wong, Martin C.S., Jing Liu, Shenglai Zhou, Shiwei Li, Xuefen Su, Harry H. X. Wang, Roger Y. N. Chung, Benjamin H. K. Yip, Samuel Y. S. Wong, and Joseph T. F. Lau, “The Association between Multimorbidity and Poor Adherence with Cardiovascular Medications,” International Journal of Cardiology 177:2 (2014): 477-82. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.103. URL: https://www.internationaljournalofcardiology.com/article/S0167-5273(14)01823-3/abstract

Yang, Gonghuan, Lingzhi Kong, Wenhua Zhao, Xia Wan, Yi Zhai, Lincoln C. Chen, and Jeffrey P. Koplan, “Emergence of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases in China,” Lancet 372 (2008): 1697–1705. URL: https://issuu.com/world.bank.publications/docs/9781464812637

Yuan, B., D. Balabanova, J. Gao, S. Tang, and Y. Guo, “Strengthening Public Health Services to Achieve Universal Health Coverage in China,” BMJ 365 (June 21, 2019): 12358. URL: https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l2358.long

Yue, Zhao, Wang Bin, Qi Weilin, and Yang Aifang, “Effect of Medication Adherence on Blood Pressure Control and Risk Factors for Antihypertensive Medication Adherence,” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 21:1 (2014): 166-72. doi:10.1111/jep.12268. URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jep.12268

Zhang, L., G. Cheng, S. Song, et al., “Efficiency Performance of China’s Health Care Delivery System,” International Journal of Health Planning Management 32 (2017): 254-263. doi:10.1002/hpm.2425 pmid:28589685. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28589685

Zhao, Y., E. M. Crimmins, P. Hu, Y. Shen, J. P. Smith, J. Strauss, J., and Y. Zhang, “Prevalence, Diagnosis, and Management of Diabetes Mellitus among Older Chinese: Results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study,” International Journal of Public Health 61:3 (2006): 347-356. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4880519/

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email