Black Markets for License Plates in Chinese Megacities

Chinese megacities ration new car sales by capping the number of license plates they issue that permit driving within city limits. Concerns regarding the fairness of this policy have led city governments to use lotteries to allocate either all or a share of the license plates. Lotteries create gains from trade that have stimulated black markets for license plates in such cities as Beijing and Hangzhou. Though black markets are usually considered undesirable, they can correct for distortionary regulations. A recent literature evaluates the trade-offs between equity and efficiency that are inherent to a city′s choice of mechanism to allocate its license plates. In spite of the substantial estimated volume of trade in Beijing’s black market for license plates, most of the gains from trading license plates are lost to transaction costs.

Due to concerns about escalating congestion and pollution, Chinese megacities have adopted schemes to ration license plates, as a means to control the number of cars permitted to drive within the city limits. The choice of allocation mechanism for the license plate quota creates a tension between economic efficiency and fairness. Shanghai’s auction mechanism, in place since 2002, allocates the license plates to those who value them the most. However, the escalation of Shanghai auction prices, which are currently on par with the price of a new car, has led to concerns regarding fairness. Survey evidence shows that citizens disapprove of auctions (Li, 2018).

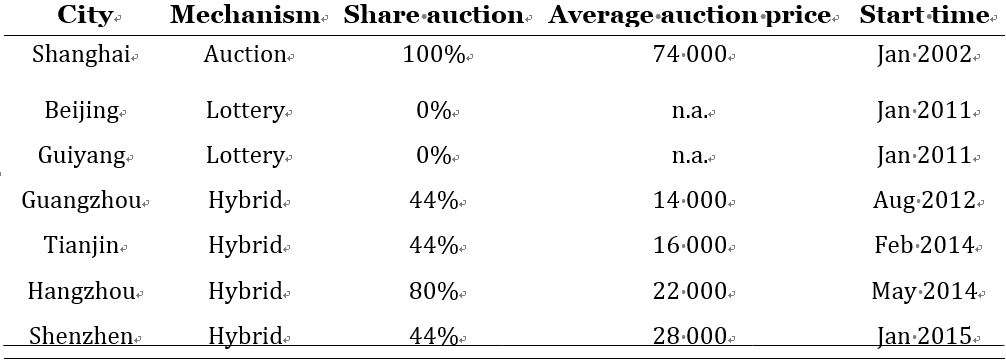

Subsequently, Beijing adopted a lottery mechanism in 2011 to maintain a perception of equity (Huang & Wen, 2019; Li, 2018). Later, the cities of Guangzhou, Tianjin, Hangzhou, and Shenzhen chose hybrid mechanisms that allocate part of the plates by auction, and part by lottery. See Table 1 for an overview.Table 1: Table based on Table 1 in Huang and Wen (2019). All prices in RMB.

These hybrid allocation mechanisms strike a balance between efficiency and equity in places where auctions are politically undesirable. However, lotteries create incentives among lottery winners and rationed car buyers to trade plates. Though license plates are not transferable, Daljord, Pouliot, Hu, and Xiao (2019) documents numerous news reports of the emergence in Beijing of a black market for license plates soon after the introduction of the lottery. Trade takes place on dedicated online sites and through intermediaries, such as car dealerships. Rentals seem to be the most common kind of transaction, but formal license plate ownership can reportedly be acquired through corrupt officials (e.g., New York Times, 2016)(see Note 1). News outlets also report black markets in other cities (see Note 2). Examples abound of rent-seeking behavior online, such as advertisements for license plates sales or rentals and for companies that broker rentals. Figure 1 shows an example from the website of the company atzuche.com, which acts as an intermediary in the black market. In spite of stringent enforcement of the requirement for a license plate to drive within the city limits, there is anecdotal evidence suggesting that there is more lenient enforcement regarding the transfer of license plates.

From

atzuche.com. “Is your idle license plate late expiring soon? A license

plate needs to be attached to an automobile within one year from

acquisition. Otherwise the license plate will expire. If you don’t use

the plate yourself, you can purchase a car model specified by AT and

then rent it to AT. While you manage to retain the plate, you can also

get a stable rental income.” Retrieved December 7, 2019.

Given the ease with which governments could foreclose black markets by permitting resale, the costs of prohibitive enforcement seem insufficient to explain the lax enforcement of black-market trade. Black markets may however serve an economic purpose: they can counter inefficiencies by reallocating license plates to the car buyers who value the license plates the most. The combination of a lottery and a black market serves effectively as a hybrid allocation mechanism that can correct some of the most severe misallocations while maintaining a sense of fairness, similar to the auction/lottery hybrids in cities like Tianjin and Guangzhou. By a Coase theorem argument, the black market can realize a fully efficient allocation in the absence of transaction costs: transactions take place until all gains from trade are exhausted. The fact that black markets are illegal, however, creates transaction costs, which include non-pecuniary costs, such as search costs and potential legal liabilities. Daljord et al. (2019) estimates that 7 to 28 percent of the potential gains from trade are lost to transaction costs in the Beijing black market.

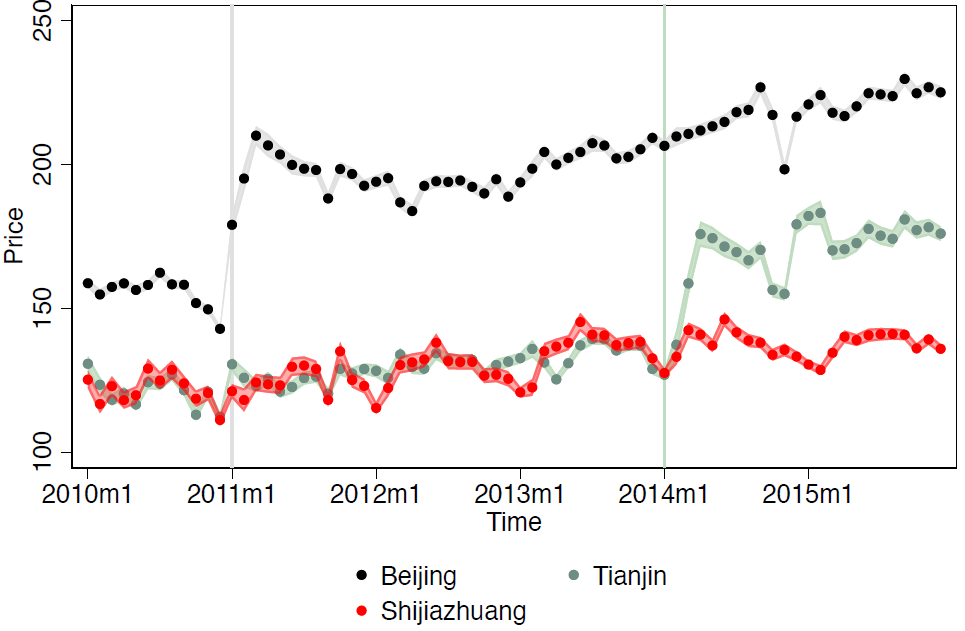

Due to their illegal nature, black market transactions are not directly observed, but can be inferred from from data on connected markets. Figure 2 shows the average prices of new cars in Beijing and the nearby cities of Tianjin and Shijiazhuang. The prices show a conspicuous, post-lottery upward shift in Beijing of about 20 percent, with no similar shift in Tianjin and Shijiazhuang. Following the rationing, the prices in Beijing have caught up with and, as of 2014, even exceed the prices in Shanghai. If the lottery randomly selected car buyers, if there was no change in the pricing of cars, and if preferences were stable, then one would expect the average price to follow the trends. Instead, the upward shift in prices in Beijing is consistent with a black market that reallocates the license plates to wealthier car buyers, who buy more expensive cars (Li, 2018; Xiao, Zhou, & Hu, 2017). Tianjin experienced a similar jump in prices to the one in Beijing, albeit at a later time. As Figure 2, shows, Tianjin’s jump in prices coincides with the introduction of a hybrid auction/lottery rationing mechanism in January 2014, which allocated 44 percent of the license plates by auction and by design selects a wealthier subset of car buyers. The comparable circumstances and magnitude of the jump in prices suggest that Beijing’s black market reallocated a material share of license plates to wealthier car buyers.

Other policies may have affected car sales. The Beijing subway system has expanded rapidly over two decades, from 39 stations in 2002 to more than 300 in 2014. In particular, a number of new lines opened in December 2010, when the rationing went into effect, and which expanded the network from 228 to 336 km (Xie, 2016). Public transportation appeals disproportionately to lower-income households, which may subsequently select out of the car market, leading to a shift in the composition of demand that is unrelated to the rationing. Since the subway expansion in 2010 coincided with the rationing, it is hard to directly test this alternative account in the data. There were however three other major subway expansions: in December 2012 (70 km), May 2013 (57 km), and December 2014 (62 km). Figure 2 shows no similar jumps in the Beijing prices during any of these expansions, which suggests the effect of the expansion in December 2010 was also modest.

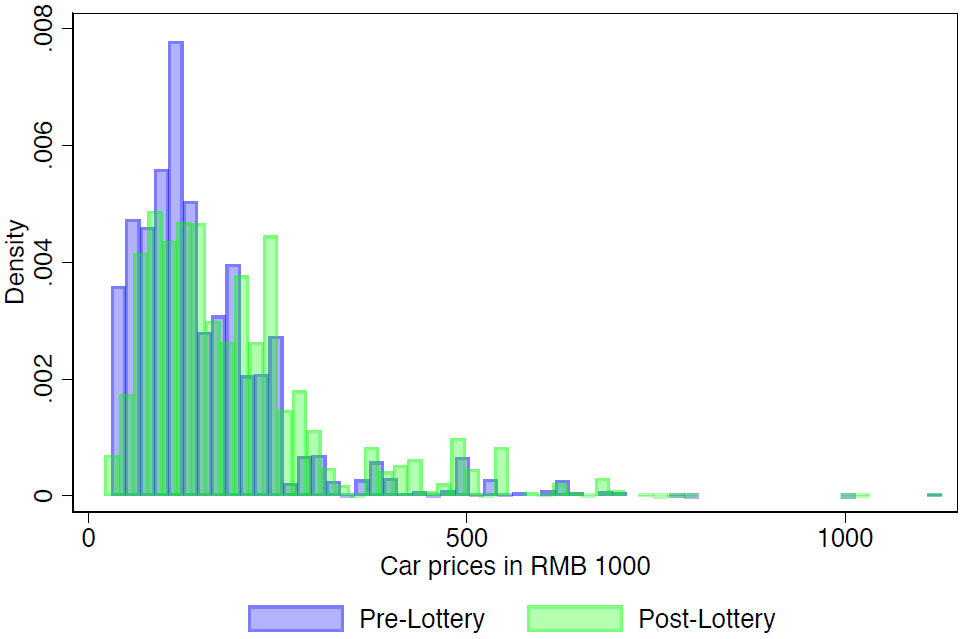

The price shift could also reflect a supply-side price response to the market contraction. However, a national policy of resale price maintenance precluded Chinese dealerships from adjusting their prices in response to the market contraction (Li, 2018). A comparison of same-model prices before and after the lottery confirms no change.While the difference-in-differences analysis of the average car prices suggests the existence of a black market, it does not directly indicate the volume of trade. Daljord et al. (2019) devises an empirical strategy to reveal information about the volume of trade from the shift in the distribution of car sales and the lottery allocation of license plates. Figure 3 provides the sales distributions one year before the rationing and two years after. The data show a clear shift toward sales of more expensive car models, which is consistent with a reallocation of license plates, but this shift is inconsistent with what we would expect from a lottery that randomly selects car buyers.

A simple and intuitive means to estimate black-market trade determines the smallest amount mass that must shift from the pre-lottery distribution to give the post-lottery distribution. This estimator detects trade when a license plate buyer purchases a different car than the license plate seller would have purchased, had the latter not sold her license. However, a transaction goes undetected if it is between a license plate buyer who purchases the same car as the license plate seller would have purchased, had she not sold the license plate. The estimator therefore generates a lower bound on the black market trade.

A specific example is instructive. Suppose cars sell either at a price of 1 or a price of 2. Pre-lottery, 80 thousand cars sell: 60 thousand at the price of 1, and 20 thousand at price 2. The population sales distribution is . Post-lottery, the quota is set at 40 thousand cars. In that instance, 10 thousand sell at the price of 1, and 30 thousand at the price of 2, such that the population sales distribution is

. Post-lottery, the quota is set at 40 thousand cars. In that instance, 10 thousand sell at the price of 1, and 30 thousand at the price of 2, such that the population sales distribution is  . In this case, at least 20 thousand license plates must be traded to rationalize the shift in the sales distribution.

. In this case, at least 20 thousand license plates must be traded to rationalize the shift in the sales distribution.To avoid confounding the black-market effects with shifts in the sales distribution that are unrelated to the rationing, Daljord et al. (2019) derives an estimator (similar to difference-in-differences) that uses the shift in the sales distributions in Tianjin, where there was no rationing during the same period, to estimate what a shift in the Beijing sales distribution would have been if not for the black market. This intuition is formalized as an optimal transport problem (Galichon, 2016) and gives a fully non-parametric estimator. The lower-bound estimate of the volume of trade is 11 percent of the quota.

A simple equilibrium model of the black market generates informative bounds on the corresponding gains from trade and transaction costs. The model takes recent estimates from Li (2018) of willingness to pay for Beijing license plates as inputs to derive black-market demand and supply for license plates. It infers transaction costs as a tax on black-market transactions that rationalizes the estimated volume of trade. The market model uses the estimated bounds on the volume of trade, along with the transaction prices reported in the news, to bound the gains from trade and transaction costs. The analysis concludes that, under plausible assumptions, between 61 and 82 percent of the net gains from trade in the Beijing black market are lost to transaction costs. Huang and Wen (2019) finds that the auction/lottery hybrid used in Guangzhou realized 83 percent of the potential gains from trade. The upper bound to the corresponding estimate for the Beijing lottery is 28 percent, which reflects a substantially different trade-off between equity and efficiency.

The lottery likely attracts speculators, that is, rent-seeking agents who enter the lottery without the intention to purchase a car. Daljord et al (2019) treats this case as an extension. Speculators have two effects in the model. The first is to crowd car buyers out of winning the lottery and therefore shift the demand curve out. The second is to flatten the supply curve since, by definition, the license plate has no value to a speculator, except to trade. If speculators fully crowd out the lottery winners, the lower bound to the net gains from trade decreases by RMB 200 million, or about 15 percent relative to a case that assumes no speculators.

The evidence points to a sizable black market for Beijing license plates with strong pecuniary incentives to trade: the average annual salary in Beijing, which was about RMB 60 thousand in the period studied, is in the lower range of the estimated transaction prices. In light of the incentives to trade, the volume of black-market trade seems modest and suggests that enforcement is effective in maintaining equity—at the cost of efficiency.

Note 1: The former head of the Beijing Traffic Management Bureau News was sentenced to life in prison in 2015 for selling license plates.

Note 2: See e.g. from Shenzhen, Hangzhou, and Guangzhou.

(Oystein Daljord, Chicago Booth School of Business, University of Chicago; Mandy Hu, CUHK, Department of Marketing; Guillaume Pouliot, Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago; Junji Xiao, Department of Economics, UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney.)

References

Daljord, O., G. Pouliot, M. Hu, and J. Xiao (2019). The black market for Beijing license plates. Working paper, Becker Friedman Institute.

Galichon, A. (2016). Optimal transport methods in Economics: Princeton University Press, New York.

Huang, Y., and Q. Wen (2019). Auction lottery hybrid mechanisms: Structural model and empirical analysis. International Economic Review 60(1), 355–385.

Li, S. (2018). Better lucky than rich? Welfare analysis of automobile license allocations in Beijing and Shanghai. The Review of Economic Studies 85(4), 2389– 2428.

New York Times (2016). Want to drive in Beijing? Good luck in the license plate lottery. July 28th

Xiao, J., X. Zhou, and W.-M. Hu (2017). Welfare analysis of the vehicle quota system in China. International Economic Review 58(2), 617–650.

Xie, L. (2016). Automobile usage and urban rail transit expansion: evidence from a natural experiment in Beijing, China. Environment and Development Economics 21 (5), 557–580.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email