Production Networks and Firm Value: Evidence from the US-China Trade War

This paper discusses the effects on the financial markets of the several rounds of tariff hikes during the 2018–19 US-China trade war. It illustrates that US firms that are more dependent on exports to and imports from China have lower stock prices around the announcement date, while the expectation of weakened Chinese import competition due to US tariffs plays an economically minimal role. Firms with indirect exposure to US-China trade through domestic supply chains also experience more negative stock returns, with the magnitude of the effects sometimes even greater than the direct trade exposure. The differential responses are not due to firms’ short-term overreactions, and are observed two months after the initial announcement in March 2018.

After almost two years of “trade war” tensions between the US and China, President Trump signed an initial trade deal with China on January 15, 2020, bringing the first chapter of a protracted and economically damaging fight with China, one of the world’s largest economies to a close (see Note 1). In this paper, we examine the implications of the trade war on the US and Chinese financial markets.

The economic implications of the US government’s move toward trade protectionism are ambiguous. The rationale for raising tariffs and transferring profits from a trade partner to home is based on the conventional mindset that global trade mostly involves the exchange of finished goods, rather than intermediate inputs. However, studies have shown that global trade in the twenty-first century has increasingly involved production sharing by firms located in different countries (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2006; Baldwin 2011; Johnson and Noguera 2012). From this perspective, firms from different nations are connected as buyers and suppliers along the global value chains. In this study, we use the 2018–19 US-China trade war announcements for an event study of firms’ global production networks.

In order to evaluate the financial implications of policy shocks for global production networks, we use the announcements of tariff increases on a wide range of goods by the US and Chinese governments in 2018–19 as events, starting with the presidential memorandum issued by the Trump administration on March 22, 2018, to study the impact of trade policy shocks on firms’ stock market performance. We document that firms’ stock market responses to the announcements are determined by the degree of their direct exposure to US-China trade, particularly their indirect exposure through global value chains. In particular, US firms that are more dependent on production networks from China have lower stock returns and higher default risk around the announcement dates. Two reverse experiments in 2019 further validate how the complex structure of global trade shapes stock market reactions to policy shocks.

A notable feature of globalization in the past few decades has been the unprecedented reorganization of economic activities across regions, firms, and workers. This reorganization has been driven by the establishment of numerous complex global value chains, which have enhanced the connectivity between firms and, hence, nations. Although the resulting increase in the interdependence of firms and nations has allowed for greater sharing of economic benefits (Acemoglu et al. 2016b), it has also amplified the propagation of shocks across complex production networks and thus increased macroeconomic uncertainty (Acemoglu et al. 2016a; Barrot and Sauvagnat 2017; Carvalho et al. 2017; Ozdagli and Weber 2017; Pasten, Schoenle, and Weber 2019).

Methodology

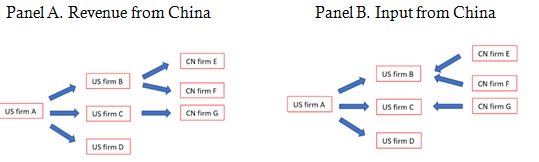

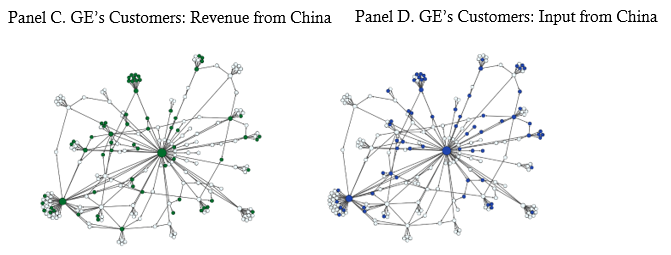

We use a novel dataset that reports firms’ intertwining input-output relationships, together with various datasets on companies’ financial outcomes and international trade, to assess a US (Chinese) firm’s direct exposure to imports from and exports to China (the US), as well as US firms’ indirect exposure to trade with China through their engagement in global value chains. In particular, we construct several measures of the indirect exposure to trade with China, using firm-level production networks and trade data. In constructing the measures, we follow Acemoglu et al. (2016a), who analyze how shocks are amplified and propagated through industry input-output links including buyer and supplier linkages.Figure 1. Firm Production Networks: Customer Side

As illustrated in Panel B of Figure 1, US firm A has three US customers, among which firms B and C have Chinese firms as their suppliers. The tariff hikes increase the cost of the Chinese inputs for B and C, potentially leading to a decline in their total production and the demand for goods produced by firm A. In contrast, if the intermediate goods produced by Chinese firms E and F can be sufficiently substituted by goods produced by US. firm A, then the tariff hike may also increase the demand for the goods produced by firm A and boost its sales. The same product network of GE is plotted in Panel D of Figure 1, where the blue nodes indicate GE customers that have outsourced input from China.

Evidence from the Financial Market

We estimate the effects of the trade-war announcements on firms’ stock values, through both direct and indirect exposure to US-China trade. In the three-day window surrounding March 22, 2018, US publicly listed companies that export more to (or import more from) China experienced lower stock returns. Specifically, in that three-day period, after controlling for standard firm-level characteristics and industry fixed effects, we find that a 10% increase in a firm’s share of sales to China is associated with a 0.5% lower average cumulative abnormal stock return (CAR), while firms that directly source inputs from China have a 0.6% lower average cumulative abnormal stock return than those that do not. These results imply that US tariffs were perceived to substantially raise the prices of imported inputs from China, and thus US companies’ production costs.When expanding the event window to over 20, 40, 60, and 80 days, respectively, we still find these negative financial market responses. We also uncover significantly positive market responses for the exposed firms to the progress made during rounds of the US-China trade talks in 2019. On the Chinese side, the effects of the March 22 memorandum on the stock market were also substantial. Chinese firms listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen that are more dependent on sales in the US demonstrated lower stock returns in that three-day window, but those that import US intermediate inputs did not experience lower stock returns.

Firms’ indirect exposure to US-China trade also matters. Our event-study regressions show that the coefficients on the average revenue from China across a firm’s customers and suppliers are both statistically and economically significant, after their direct exposure measures are included in the regression. Specifically, we find that a 10% increase in indirect sales exposure through buyers is associated with 1.1% lower CAR over the three days surrounding March 22. Our regression results also show that a 10% increase in indirect sales exposure to suppliers is associated with 0.9% lower CAR. The effects remain significant when the indirect measures based on buyers and suppliers are jointly estimated in the regression and when industry fixed effects are included. The estimated coefficients in the regression model suggest the overall indirect exposure to sales in China has a larger impact than direct exposure.

Conclusion

In this paper, we examine the effects on the financial markets of the Trump administration’s announcement of a trade war against China on March 22, 2018. We find that US firms that are more dependent on exports to and imports from China have lower stock prices in the short window around the time of the announcement. We further examine whether firms’ indirect exposure to trade with China through their domestic supply chains may also affect their responses to various tariff announcements. As predicted by our theoretical model, we find more negative responses by firms that have greater indirect exposure to exports to and imports from China through their domestic supply chains, even after controlling for the firms’ direct output and input exposure in baseline regressions.In addition, we find that despite not directly importing inputs from China, US firms that have indirect exposure to Chinese inputs through their domestic supply chains tend to experience more negative stock returns. These results suggest that the perceived increases in the input and production costs of the upstream and downstream firms are passed to the firms they are connected with through their domestic trade links. The stock price decline tends to be greater for firms that have domestic suppliers or buyers that derive a large share of their revenue from China. This suggests that even if a firm is not directly exposed to US-China trade, its stock returns will be more negatively affected if its downstream buyers or upstream suppliers are perceived to sell less to China as a result of the expected retaliatory tariffs.

To conclude, firms’ indirect exposure to US-China trade through domestic supply chains is associated with negative stock return responses that are comparable to those associated with direct exposure. These responses indicate that the complex structure of global trade plays a crucial role in the financial markets. Our findings show that the winners and losers in the bilateral US-China trade relationship are determined by their position (upstream or downstream) and the extent of their participation in the global value chains shared by the two countries.

Note 1: Ana Swanson and Alan Rappeport, “Trump Signs China Trade Deal, Putting Economic Conflict on Pause,” New York Times, January 16, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/15/business/economy/china-trade-deal.html.

(Yi Huang is Associate Professor of International Economics and Pictet Chair in Finance and Development at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva; Chen Lin is chair of Finance at the Faculty of Business and Economics of The University of Hong Kong; Sibo Liu is Assistant Professor of Lingnan University; Heiwai Tang is Professor of Economics and Associate Director of the Institute for China and Global Development at the University of Hong Kong.)

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Vasco M. Carvalho, Asuman Ozdaglar, and Alireza Tahbaz-Salehi. 2012. “The Network Origins of Aggregate Fluctuations.” Econometrica, 80(5), 1977–2016. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA9623.

Acemoglu, Daron, Ufuk Akcigit, and William Revill Kerr. 2016a. “Networks and the Macroeconomy: An Empirical Exploration.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 30(1): 276–335. https://doi.org/10.1086/685961.

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, Amir Kermani, James Kwak, and Todd Mitton. 2016b. “The Value of Connections in Turbulent Times: Evidence from the United States. ”Journal of Financial Economics, 121(2), 368–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.10.001.

Baldwin, Richard. 2011. “Trade and Industrialisation after Globalisation’s 2nd Unbundling: How Building and Joining a Supply Chain Are Different and Why It Matters.” NBER Working Paper No.17716. https://www.nber.org/papers/w17716.

Barrot, Jean-Noel, and Julien Sauvagnat. 2016. “Input Specificity and the Propagation of Idiosyncratic Shocks in Production Networks.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(3), 1543–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw018.

Carvalho, Vasco M., Makoto Nirei, Yukiko U. Saito, and Alireza Tahbaz-Salehi. 2017. “Supply Chain Disruptions: Evidence from the Great East Japan Earthquake.” Northwestern University Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2893221.

Grossman, Gene M., and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. 2006. “The Rise of Offshoring: It’s Not Wine for Cloth Anymore.” Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 59–102. https://www.princeton.edu/~erossi/RO.pdf.

Huang, Yi, Chen Lin, Sibo Liu, and Heiwai Tang. 2018. “Trade Linkages and Firm Value: Evidence from the 2018 US-China ‘Trade War.’” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3227972.

Johnson, RobertC., and Guillermo Noguera. 2012. “Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value Added.” Journal of International Economics, 86(2), 224–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.10.003.

Ozdagli, Ali, and Michael Weber. 2017. “Monetary Policy through Production Networks: Evidence from the Stock Market.” NBER Working Paper No.23424. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23424.

Pasten, Ernesto, Raphael Schoenle, and Michael Weber. 2019. “The Propagation of Monetary Policy Shocks in a Heterogeneous Production Economy.” Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2019.10.001.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email