The Hidden Cost of Trade Liberalization: Input Tariff Shocks and Worker Health in China

Can intermediate input trade liberalization affect worker health in a developing country like China, and if so, how? Do the impacts differ between skilled and unskilled workers? What are the welfare implications of input tariff reductions once health factors are considered? Professors Haichao Fan of Fudan University, Faqin Lin of China Agricultural University, and Shu Lin of the Chinese University of Hong Kong develop...

Recently, a growing strand of literature has started to examine the health effects of trade shocks (e.g., Hummels et al., 2016; McManus and Schaur, 2016; Pierce and Schott 2016; Bombardini and Li, 2020). While most existing work focuses on import competition or export expansion, less is known about the role of input tariffs. Using input tariffs and the China Health and Nutrition Survey data (CNHS), this study (Fan, Lin, and Lin, 2020) finds that input tariff reductions adversely affect worker health through increased working hours. Moreover, input tariff reductions widen both the income and the health gaps between skilled and unskilled workers. Further welfare analysis indicates that ignoring health outcomes would substantially underestimate the welfare disparity between skilled and unskilled workers.

Four Stylized Facts

We first document four stylized facts regarding input tariffs, workers’ working hours, wages, and health before and after China’s WTO accession:

Fact 1: There were large tariff cuts following China’s WTO accession, and the reductions applied mainly to imports of intermediate goods.Fact 2: There was a large increase in the likelihood of experiencing injury or illness for Chinese manufacturing workers after China joined the WTO.

Fact 3: After trade liberalization, Chinese manufacturing workers’ working hours and wages both increased.

Fact 4: After trade liberalization, unskilled workers experienced larger increases in illness rates and working time but a smaller gain in income.

A Theoretical Model

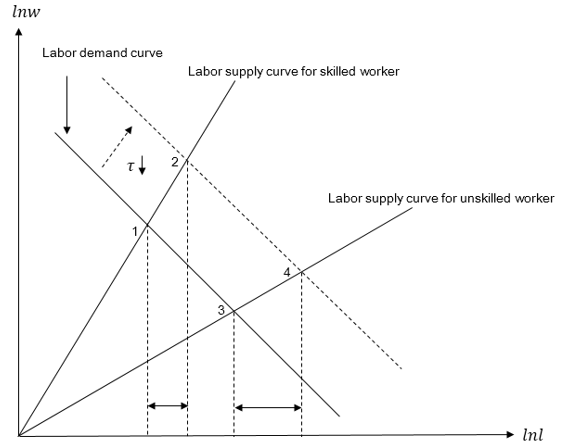

To rationalize these facts and to motivate our empirical exercises, we build an illustrative model linking input tariff reductions to firm behavior, workers’ supply of labor, and their health status. In our model, firms choose the number of workers and each worker’s optimal working time. The optimal working time and the number of employed workers are substitutes and are both decreasing functions of the wage rate. To hire workers, firms need to pay a search cost (e.g., Helpman and Itskhoki 2010; Helpman et al., 2010). The impact of a reduction in input tariffs on firms’ demand of working time can be illustrated intuitively using a simple diagram (Figure 1). A reduction in input tariffs lowers a firm’s marginal costs and increases its profit. The demand curve for working time is accordingly shifted to the right.

Workers in our model choose optimal working time to maximize their utility. The supply curve of working time is an increasing function of the wage rate. Based on existing findings in the labor economics literature (e.g., Juhn et al., 1991, 2002), we assume that the elasticity of labor supply to the wage rate is lower for skilled workers. As a result, in Figure 1, the supply curve of working time for skilled workers is steeper than for unskilled workers. Consequently, a rightward shift of the demand curve following trade liberalization has differential effects on skilled and unskilled workers. While equilibrium working hours and wages increase for both types of workers, the increase in working hours (wages) for unskilled workers is larger (smaller). Existing studies in the medical literature have provided overwhelming evidence on a positive association between working time and the likelihood of experiencing illness or injury (e.g., Sparks and Cooper, 1997; van der Hulst, 2003; Dembe et al., 2005). Rod et al. (2017), Hamermesh et al. (2017), and Berniell and Bietenbeck (2018) provide further causal evidence. Longer working hours, therefore, lead to a higher probability of becoming injured or ill, both the income gap and health gap widen following trade liberalization.Figure 1. Optimal working hours and wage payment

Empirical Strategy

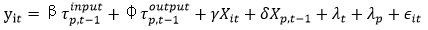

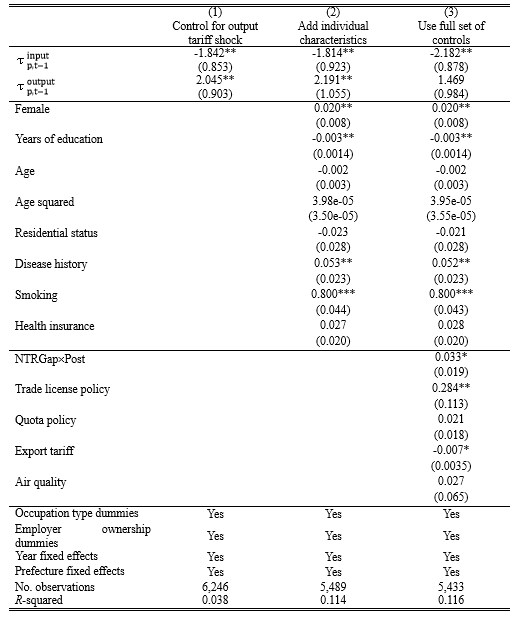

We then put the predictions of our theoretical model to a test. Following the literature (e.g., Amiti and Konings 2007; Topalova, 2010), we construct a prefecture-level input tariff shock measure using the Chinese provincial-level input-output table and the prefecture-level initial industry composition of labor. Employing the CHNS database, we estimate the following specification.

, where i and t represent the individual and year, respectively.

, where i and t represent the individual and year, respectively.  measures the health condition of individual i in year t. Our main measure of workers’ health status is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if an individual has experienced illness or injury in the past four weeks and 0 otherwise. We also consider two alternative measures for robustness. First, since the CHNS survey provides information about whether a worker has felt uncomfortable or exhausted in the past four weeks, we will use this binary variable as an alternative. Second, we also utilize workers’ subjective evaluations of the severity of illness or injury as another alternative. The self-evaluated score ranges from 1 (the least severe) to 3 (the most severe). In addition, we will also examine the effects on different types of illness using a set of binary indicators.

measures the health condition of individual i in year t. Our main measure of workers’ health status is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if an individual has experienced illness or injury in the past four weeks and 0 otherwise. We also consider two alternative measures for robustness. First, since the CHNS survey provides information about whether a worker has felt uncomfortable or exhausted in the past four weeks, we will use this binary variable as an alternative. Second, we also utilize workers’ subjective evaluations of the severity of illness or injury as another alternative. The self-evaluated score ranges from 1 (the least severe) to 3 (the most severe). In addition, we will also examine the effects on different types of illness using a set of binary indicators.

, the one-year lagged input tariff shock measure, is our variable of interest. We expect the estimated coefficient on this key variable to be negative and significant, which would indicate an adverse effect of input tariff reductions on worker health. We also include output tariffs in the regression and we expect the output tariff shock to have an ambiguous effect on worker health. On the one hand, the declines in output tariffs may lead to better worker health outcomes due to reduced working hours. On the other hand, there can also be some negative effects on worker health associated with unemployment (or underemployment), ranging from stress related to job loss to being unable to afford proper health care.

, the one-year lagged input tariff shock measure, is our variable of interest. We expect the estimated coefficient on this key variable to be negative and significant, which would indicate an adverse effect of input tariff reductions on worker health. We also include output tariffs in the regression and we expect the output tariff shock to have an ambiguous effect on worker health. On the one hand, the declines in output tariffs may lead to better worker health outcomes due to reduced working hours. On the other hand, there can also be some negative effects on worker health associated with unemployment (or underemployment), ranging from stress related to job loss to being unable to afford proper health care.

is a comprehensive set of individual-level controls, including gender, years of education, age, age squared, disease history, smoking, possession of health insurance, occupation type dummies, and employer ownership dummies. We also control for a set of prefecture-level covariates,

is a comprehensive set of individual-level controls, including gender, years of education, age, age squared, disease history, smoking, possession of health insurance, occupation type dummies, and employer ownership dummies. We also control for a set of prefecture-level covariates,  , in our benchmark specification. Following Facchini et al. (2019), we include in

, in our benchmark specification. Following Facchini et al. (2019), we include in  a set of prefecture-level measures of other policy changes, including the elimination of trade uncertainty (Handley and Limao, 2017; Erten and Leight, 2019; Facchini et al., 2019) and export licenses (Bai et al., 2017), changes in quotas due to the expiration of global MFA, and changes in tariffs on China’s exports abroad. In addition, we also include in

a set of prefecture-level measures of other policy changes, including the elimination of trade uncertainty (Handley and Limao, 2017; Erten and Leight, 2019; Facchini et al., 2019) and export licenses (Bai et al., 2017), changes in quotas due to the expiration of global MFA, and changes in tariffs on China’s exports abroad. In addition, we also include in  a prefecture-level measure of air quality to capture the effect of air pollution on health.

a prefecture-level measure of air quality to capture the effect of air pollution on health.  is the year fixed effects, which captures yearly shocks common to all individuals. We also include prefecture fixed effects,

is the year fixed effects, which captures yearly shocks common to all individuals. We also include prefecture fixed effects,  , to control for all time-invariant differences across prefectures in our regressions.

, to control for all time-invariant differences across prefectures in our regressions.  is the error term.

is the error term.

What Do We Find?

We find that manufacturing workers in Chinese prefectures that had a larger exposure to input tariff reduction shocks experienced a significantly higher likelihood of suffering from illness or injury. This finding is not affected by controlling for other trade shocks and pollution variables. It is also robust to using only the two waves of the survey data closest to China’s WTO accession. In a comprehensive set of tests, we also rule out the possibility that our results are driven by pre-existing trends. Additional evidence from the placebo tests lends further support to our hypotheses.

Table 1. Benchmark results

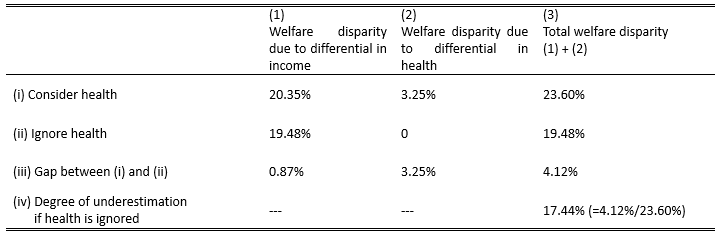

We then move one step forward to examine the differential effects of input tariff liberalization on workers with different skill levels. We show that input trade reductions not only widen the income gap between skilled and unskilled workers but also have a significantly larger adverse effect on health conditions of the unskilled. To shed light on the underlying channel, we also investigate the effects of input tariff reductions on daily working hours. Consistent with our theoretical model, we find that input tariff reductions also have a significantly larger effect on working hours for the unskilled.

Finally, we conduct a welfare analysis based on our model and the empirical results. We find that taking the health effect into consideration is quantitatively important for correctly calculating the welfare disparity between skilled and unskilled workers. The welfare disparity becomes significantly larger if health factors are accounted for. For instance, consider workers with more than a compulsory-level education and those with less than a compulsory-level education: ignoring the differential effects on health would result in an underestimation of welfare disparity by 17.44%.

Table 2. Welfare disparity between skilled and unskilled workers (for a one standard deviation reduction in input tariff shock)

An important takeaway from our study is that, while workers consider disutility due to longer working hours in their labor supply decisions, they fail to realize the additional “hidden” health costs. This is consistent with findings documented by recent studies in the labor economics literature (e.g., Blattman et al., 2018). We show that, once adjusted for the health costs, the wealth disparity between skilled and unskilled caused by trade liberation can be even larger. The policy implication of our results is certainly not anti-liberalization, as globalization can has large beneficial effects not examined in our study on individual workers. Rather, our results highlight the important roles for information and government regulations on labor protection measures, such as work safety requirements and maximum daily working hours, which are weak in China and developing countries in general. Improvement in information and labor protection measures can help alleviate the adverse health effects.

References

Amiti, Mary, and Jozef Konings. 2007. “Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs, and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia.” American Economic Review, 97: 1611–1638.

Bai, Xue, Kala Krishna, and Hong Ma. “How you export matters: Export mode, learning and productivity in China.” Journal of International Economics, 2017, 104: 122–137.Berniell, Ines, Bietenbeck, Jan, 2018. “The Effect of Working Hours on Health,” Working Paper.

Blattman, Christopher, Dercon, Stefan, 2018. “The impacts of industrial and entrepreneurial work on income and health: experimental evidence from Ethiopia”. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 10(3), 1–38.

Bombardini, Matilde, and Bingjing Li. 2020. “Trade, pollution and mortality in China.” Journal of International Economics, 125.

Dembe, Allard E., Erickson, Jeffery B., Delbos, Rachel, Banks, Steven M., 2005. “The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: new evidence from the United States.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(9), 588–597.

Erten, Bilge and Jessica Leight. 2019. “Exporting out of agriculture: The impact of WTO accession on structural transformation in China.” Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Facchini, Giovanni, Maggie Liu, Anna Maria Mayda, and Minghai Zhou. 2019. “China’s “Great Migration”: The impact of the reduction in trade policy uncertainty.” Journal of International Economics, 120: 126–144.

Fan, Haichao., Faqin Lin, and Shu Lin. 2020. “The hidden cost of trade liberalization: Input tariff shocks and worker health in China.” Journal of International Economics, forthcoming.

Hamermesh, Daniel S., Kawaguchi, Daiji, Lee, Jungmin, 2017. “Does labor legislation benefit workers? Well-being after an hours reduction.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 44, 1–12.Handley, Kyle and Nuno Limao. “Policy uncertainty, trade and welfare: Theory and evidence for China and the U.S.” American Economic Review, 2017, 107(9), 2731–2783.

Helpman, Elhanan, and Oleg Itskhoki. 2010. “Labor market rigidities, trade and unemployment.” Review of Economic Studies, 77: 1100–1137.

Helpman, Elhanan, Oleg Itskhoki, and Stephen Redding. 2010. “Inequality and unemployment in a global economy.” Econometrica, 78(4): 1239–1283.

Hummels, David, Jakob Munch, and Chong Xiang. 2016. “No pain, no gain: The effects of exports on effort, injury, and illness.” NBER Working Paper No. 22365.

Juhn, Chinhui, Kevin M. Murphy, and Robert H. Topel. 1991. “Why has the natural rate of unemployment increased over time?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, No. 2: 75–142.

Juhn, Chinhui, Kevin M. Murphy, and Robert H. Topel. 2002. “Current unemployment, historically contemplated.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, No. 1: 79–136.

McManus, T. Clay, and Georg Schaur. 2016. “The effects of import competition on worker health.” Journal of International Economics, 102: 160–172.

Oster, Emily. 2012. “Routes of infection: Exports and HIV incidence in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(5): 1025–1058.

Pierce, Justin R., and Peter K. Schott. 2016. “Trade liberalization and mortality: Evidence from U.S. counties.” NBER Working Paper No. 22849.

Rod, Naja Hulvej, Kjeldgard, Linnea, Akerstedt, Torbjorn, Ferrie, Jane, Salo, Paula, Vahtera, Jussi, Alexanderson, Kristina, 2017. “Sleep apnea, disability pension and cause-specific mortality: A nationwide register linkage study.”American Journal of Epidemiology. 186(6), 709–718.

Sparks, Kate, Cooper, Cary, 1997. “The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 70(4), 391–408.

Topalova, Petia. 2010. “Factor immobility and regional impacts of trade liberalization: Evidence on poverty from India.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(4): 1–41.

van der Hulst, Monique, 2003. “Long workhours and health.” Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 29(3), 171–188.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email