The Quiet Revolution in Women’s Human Capital and the Gender Earnings Gap in the People’s Republic of China

Since the 1980s, girls’ educational attaintment increased more quickly than boys’. As a result, the gender education gap decreased and even reversed in China. How does the gender earnings gap change in the face of increasing female human capital? What are the implications for the Chinese gender earnings gap in the future? This column will shed light on this interesting topic within and across cohorts.

During the past few decades, women’s educational attainment experienced a “quiet revolution” and has caught up with or even exceeded men’s education in many developed countries. At the same time, the gender earnings gap steadily decreased, although it still exists today (Goldin, 2006; Blau and Kahn, 2008, 2017). In China, women have also experienced a quiet revolution in education since the 1980s (Tsui and Rich 2002; Lee 2012), yet their labor market conditions have gradually worsened and the gender earnings gap has become wider (Li et al., 2014; Gustafsson and Li, 2000; Zhang et al., 2008). Why hasn’t the gender earning and education gaps changed in China in the same direction as in developed countries? In this study, we attempt to understand the roles of education and cognitive abilities on the gender earnings gap across birth cohorts in the early 2010s’ China.

We investigate three birth cohorts: 1960–1969, 1970–1979, and 1980–1989. These three cohorts have very distinct characteristics and experiences. For example, the 1960–1969 birth cohort spent most of their childhood experiencing the Cultural Revolution, whereas the 1980–1989 birth cohort was confronted with the introduction of the one-child policy and the expansion of higher education. Because China’s market-oriented reform is through an incremental changes and dual-track transition, the labor markets faced by the older and younger cohorts can be quite different even in the same time point. Therefore, looking into the gender earnings gap across birth cohorts in a particular time can, to some extent, reveal another aspect of the changes in the labor market relative to looking into the gender earnings gap over time.

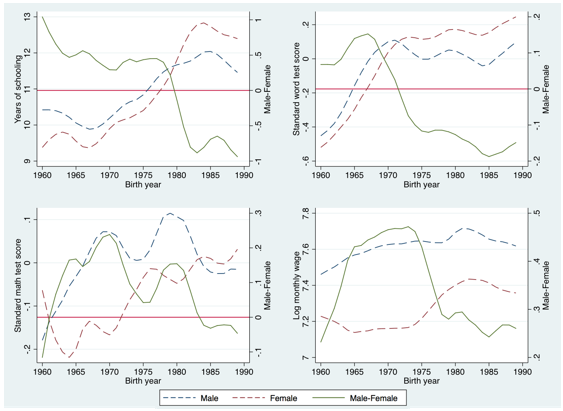

Figure 1: Changes in key variables among birth cohorts

Figure 1 shows the trends of education, cognitive ability (standard scores of word and math tests), and earnings across cohorts. The gender gap in human capital is decreasing and even appears to have a reverse condition. The gender earnings gap also narrows, but the gap still exists. Specifically, as female educational attainment rises, the gender earnings gap decreases; the gender gaps in earnings and math and word test scores have all decreased since the 1970s cohort.

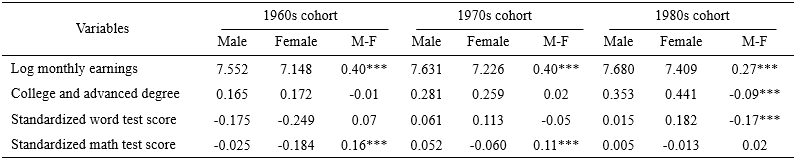

Table 1 Summary statistics

Table 1 presents the gender gaps in earnings, education, and cognitive abilities. The average earning of men is 40 log points higher (equivalent to 49%) than that of women for the 1960s and 1970s birth cohorts. However, compared to older cohorts, women’s earnings in the 1980s birth cohort increased faster than men’s, which leads to a 13 log point reduction (equivalent to 18%) in the gender earnings gap, which accounts for 36.7% of the earnings gap in the previous two cohorts.

As expected, the younger cohorts are more likely to attain higher education than older cohorts due to the continuous expansion of higher education, but women benefit more than men. Chinese women experienced a “quiet revolution” in terms of higher education and now outperform men in this respect, as was the case in the United States during the past few decades (Goldin, 2006; Blau and Kahn, 2017). Also, women have made great progress in measures of cognitive abilities in China. They reversed the gender gap previously found in word test scores and have progressed faster than men in math test scores from a position of disadvantage to one of no difference.

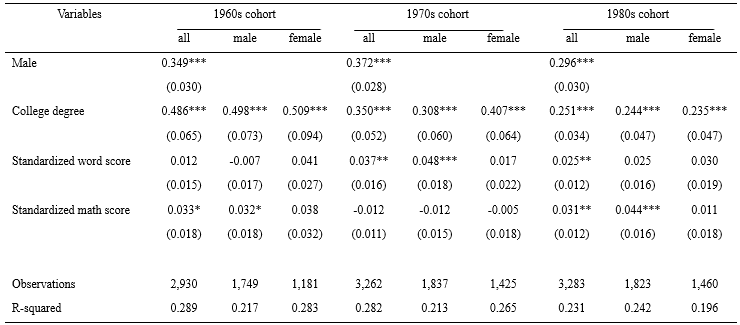

Table 2 reports the effect of human capital on earnings. Compared to those without a college degree, those with a college degree increase their earnings by about 50%, 35%, and 25% on average in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s birth cohorts, respectively. This decreasing return to college degrees may be due to the expansion of higher education and the resulting degree inflation. Different from education, the effects of cognitive abilities have no consistent pattern across cohorts.Table 2: OLS Results of earnings regression

Then, we decompose the gender earnings gap into two parts: one part comprises the gender differential of characteristics such as education, and the other one comprises the gender differential of returns to these characteristics. We call these two parts the “explained” and “unexplained” parts, respectively. Overall, the total gender earnings difference and the explained difference decrease across the cohorts. In the 1980s birth cohort, the explained part is nearly 0. This outcome means that in terms of observed characteristics, there is no difference between women and men. Further, this outcome is largely based on higher educational attainment and better word test scores. However, education and cognitive abilities do not contribute much in the 1960s and 1970s birth cohorts.

Additionally, occupation and industry make a relatively large contribution to the explained part and show a convergent trend of contributions from the older cohort to the younger cohort. In the 1980s cohort, occupation contributes nearly zero, and industry offsets years of schooling. This means that men tend to enter high-paying occupations and industries in the older cohort, but the barriers to high-paying occupations and industries gradually weakened for the younger cohorts.

In the unexplained part, the return to hukou can significantly reduce the gender earnings gap because of its high premium for women in that women have more job opportunities in urban areas compared to rural areas. Marital status makes a relatively large contribution on the increase of the gender earnings gap because the return on marriage especially favors men. A married man earns 32.8% more than an unmarried man on average in the 1960s birth cohort, which is equal to two or three years of college education. After marriage, there might be a division of labor: men tend to focus on work, while women tend to concentrate on family. This specialization within a family makes for a totally different marriage premium between the genders, and it also makes the gender earnings gap larger. The constant effect on earnings structure shows a rising trend, accounting for 31.06%, 65.63%, and 62.12% of the total gender earnings differential in the three respective cohorts. This outcome is totally unexplained, and to a large extent we can view it as discrimination.

Next, we further study the contribution of each factor to the change in the gender earnings gap across birth cohorts. The change in the gender earnings gap can be decomposed into four parts—the “observed X’s effect,” the “observed price effect,” the “gap effect,” and the “unobserved price effect.” The observed X’s effect is driven by the change of gender gap in observed characteristics across cohorts; the observed price effect is driven by the change of prices of these observed characteristics across cohorts. The gap effect is driven by the change of the gender gap in unobserved characteristics across cohorts; the unobserved price effect is driven by the change of unobserved price across cohorts. The sum of the last two parts is often viewed as discrimination.

In this decomposition, we first exclude the age effect within cohorts to focus on the change across cohorts. We find that the gender earnings gap increases by 12% from the 1960s cohort to the 1970s cohort and decreases by 21% from the 1970s cohort to the 1980s cohort. Overall, from the 1960s cohort to 1980s cohort, the gender earnings gap narrows by approximately 9%. Except for the unobserved price effect, all other effects contribute to reducing the earnings gap.

From the 1960s cohort to 1980s cohort, the education variable plays the most important role in the observed X’s effect, explaining 24.57% of the reduction of the gender earnings gap. Women gained ground in college education across the cohorts, and the high level of human capital they accumulated helped them to obtain higher wages. As women show an increase in their share of college degrees and the return on education is high for women, encouraging women to increase human capital investment is an effective way to narrow the gender earnings gap. Nevertheless, the effect is limited, as the return on education decreases with the rise in the share of college degrees.

The gap effect accounts for 52.51% of the reduction of the gender earnings differential. The gap effect represents discrimination and unobserved skills. The discrimination may result from the different treatment of the genders in the same position, for example, men being more valued than women, men being given more promotions and opportunities to accumulate working skills, or other factors that widen the gender earnings gap. Cognitive abilities may not be a good measure here and may result in the high amount of unobserved skills in the gap effect. For example, given the development of technology, computer skills may help individuals obtain jobs or higher pay. Meanwhile, computer skills are cognitive instead of manual and may improve women’s performance in the labor market.

Since the return to education decreases as the younger cohort obtains more education, we expect that women’s progress in education relative to men should slow down, and if that happens, improving women’s human capital might not be a primary or powerful driver for narrowing the gender earnings gap. Specifically, the gap effect makes the greatest contribution to the change in the gender earnings gap, which is attributed to the unobserved skills and/or discrimination. The explanation of the gap effect is somewhat monotonous, and more research should be done to investigate the content of the gap effect.

(Zhengyang Li, Research Institute of Economics and Management, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics; Guochang Zhao, Research Institute of Economics and Management, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.)

References

Blau, F. D. & Kahn, L. M. (2008). Women’s work and earnings. In: S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume, The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd ed. (pp. 762–772). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender earnings gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3): 789–865.

Goldin, C. (2006). The quiet revolution that transformed women's employment, education, and family. American Economic Review, 96(2), 1–21.

Gustafsson, B., & Li, S. (2000). Economic transformation and the gender earnings gap in urban China. Journal of Population Economics, 13(2), 305–329.

Lee, M. H. (2012). The one-child policy and gender equality in education in China: Evidence from household data. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(1), 41–52.

Li, S., Song, J.,& Liu, X. (2014). The evolution of the gender earnings gap of the staff of China’s cities and towns (In Chinese). Management World (Guan Li Shi Jie), 03, 53–66.

Tsui, M., & Rich, L. (2002). The only child and educational opportunity for girls in urban China. Gender & Society, 16(1), 74–92.

Zhang, J., Han, J., Liu, P. W., & Zhao, Y. (2008). Trends in the gender earnings differential in urban China, 1988–2004. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 61(2), 22–243.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email