Finance Leases: A Hidden Channel of China’s Shadow Banking System

We find that banks use their affiliated leasing firms to provide credit to constrained clients in order to circumvent the government’s targeted monetary tightening policy, which offsets the expected decline in traditional bank loans in overcapacity industries and hampers the effectiveness of the monetary policy. Although this regulatory arbitrage may cause systemic risk at the macro level, bank-affiliated leasing firms exhibit much tighter risk control than other non-bank-affiliated leasing firms at the micro level, indicating that banks use finance leases as a channel to support low-risk clients rather than to make excessive profit.

Shadow banking involves credit intermediation activities outside the traditional banking system. In contrast to the United States and Europe, where shadow banking activities have been under ever-increasing scrutiny since the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, China has witnessed tremendous shadow banking growth since that crisis. This paper investigates an important yet still understudied constituent of China’s shadow banking system: finance leases. Leases can be broadly classified as finance leases or operating leases based on whether the lease transfers substantially all of the risks and rewards associated with the ownership of the leased assets to the lessee. If so, the lease is a finance lease. Otherwise, it is an operating lease. Finance leases usually have longer maturities, with the leased assets being purchased by the lessee at the end of the lease, while the maturities of operating leases are usually much shorter and without transfer of ownership at the end. Finance leases account for more than 90% of the market in China (see Note 1) compared to only 30% in the United States.

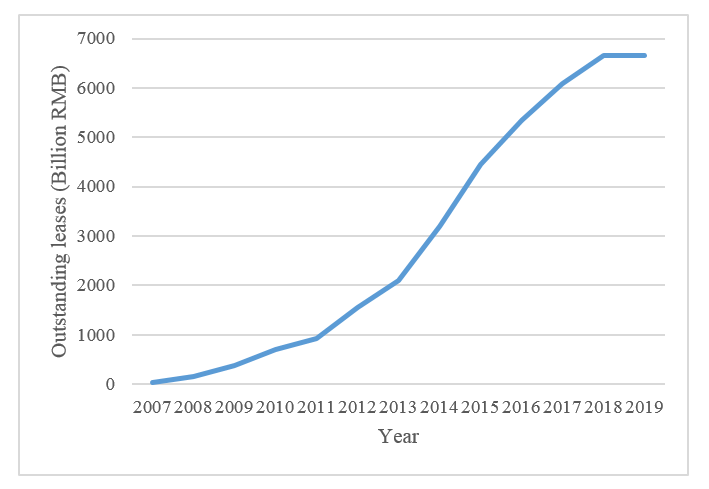

As shown in Figure 1, China’s leasing industry experienced explosive growth from 2007 to 2019. The 6.7 trillion RMB leasing market is of a comparable order of magnitude to another major constituent of China’s shadow banking system, entrusted loans, which stood at 12.4 trillion RMB as of the end of 2018 (Allen et al., 2019). Although entrusted loans have been carefully studied by academics, for example, Chen, Ren and Zha, 2019 and Allen et al., 2019, little is currently known about the leasing market in China.

By exploiting the mandatory disclosure requirements on public firms’ finance leases, we manually collected 1301 finance lease transactions from 16,952 public firms’ annual reports during the period 2007–2019. By analyzing this lease sample, we make four major discoveries.

Figure 1. China’s Outstanding Leases

First, we find that the government’s targeted monetary tightening policy stimulated the growth of finance leases. This finding is consistent with the notion that firms resort to finance leases as a channel for credit when bank loans are not available due to policy restrictions. The targeted monetary tightening policy of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and China’s Bank Regulatory Committee (CBRC) toward firms in “overcapacity industries” (see Note 2) from December 22, 2009, to March 13, 2014 (see Note 3), provided an opportunity for us to explore the cause of the growth of finance leases. In our difference-in-difference analysis, the firms in the “overcapacity industries,” which are subject to the targeted monetary tightening policy, are the treatment group, while firms that are not affected by the policy shock constitute the control group. We find that the average treatment group firm, relative to the average control group firm, experienced an increase in the annual probability of engaging in new finance leases from 1.74% to 2.98%, assuming all other explanatory variables are at their means. Similarly, the policy caused the treatment group firms’ annual finance lease transactions as a share of total assets to increase by 0.17% from the sample average of 0.09%.

Second, we find evidence that banks use their affiliated leasing firms as a channel to conduct regulatory arbitrage. The leasing firms can be divided into bank-affiliated and non-bank-affiliated depending on whether a leasing firm’s controlling shareholder is a bank. Anecdotal evidence suggests that banks often support their affiliated leasing firms by introducing clients, exporting risk management expertise, and providing implicit guarantees. Our hypothesis is that when the policy restrictions force banks to reject high-quality loan applicants from overcapacity industries, they attempt to circumvent the policy by extending credit through their subsidiary leasing firms. From firms’ perspectives, leasing contracts with bank-affiliated leasing firms are more favorable due to the more attractive terms, for example, lower leasing rates, larger leasing amounts, and longer maturities. In the same difference-in-difference analysis framework as before, we indeed find that bank-affiliated finance leases increased significantly for firms in the treatment group compared to firms in the control group. In contrast, there is no similar significant result for leases from non-bank-affiliated leasing firms.

In addition, we find that banks use finance leases to retain their existing loan clients affected by the policy shock. We define a lease to be a bank-customer lease if the lessee received loans or credit lines from the lessor’s parent bank within five years prior to the leasing transaction. In the same difference-in-difference analysis framework as before, we indeed find that after the targeted tightening policy was launched, bank-customer leases increased significantly for treatment group firms as compared to control group firms.

Third, we advance an analysis of banks’ risk taking through finance leases. Although banks’ regulatory arbitrage through finance leases dampens the effectiveness of the targeted monetary policy, which may pose systemic risk to the economy at the macro level, it is not clear whether banks conduct regulatory arbitrage to increase their exposure to credit risk at the micro level. Different from the conventional view (Adrian and Ashcraft, 2016), which states that banks use regulatory arbitrage to conceal high-risk investments, we hypothesize that banks employ regulatory arbitrage to support low-risk clients (in the restricted industries). When a bank engages in regulatory arbitrage, the concern about alerting regulators with defaults would make the bank particularly cautious in engaging high-risk clients.

We find several pieces of evidence in support of this hypothesis. First, bank-affiliated leases charge lower leasing rates than non-bank-affiliated leases. The average adjusted rates for bank-affiliated and non-bank-affiliated leases are −0.1% and 1.0%. Meanwhile, the realized credit risk of bank-affiliated leases is lower than that of non-bank-affiliated leases. These results indicate that the bank-affiliated leasing firms are not taking excessive risk for high profit. In addition, we find that the leasing rate of bank-affiliated leases are more efficient in terms of reflecting the credit risk of the lessee than those of non-bank-affiliated leases. This result shows that bank-affiliated leasing firms can recognize credit risk and pricing risk efficiently. Finally, the bond issuance yield of bank-affiliated financial leasing firms is, on average, 70–80 bps lower than that of non-bank-affiliated firms after controlling for bond and issuer characteristics, implying the existence of implicit guarantees from parent banks. Since banks still bear the credit risk of their affiliated leasing firms, it would be natural for banks to send only low-risk clients to the affiliated leasing firms.

Fourth, we explore the economic implications of finance leases for lessees. Finance leases provide alternative low-cost financing to firms, which tend to create value for firms. Meanwhile, they may also reflect difficulties of securing loans from banks. We find that although the announcement return of a finance lease is insignificant for non-bank-affiliated leases, it is positive and significant for bank-affiliated leases. This result is consistent with the notion that the capital market regards a bank-affiliated lease as an endorsement from the bank even without a direct bank loan.

Note 1: About 84% of the finance leases are sale-and-leaseback (SLB) transactions in China. In an SLB, the owner of the asset contracts to sell the asset and to lease it back from the buyer (the lessor). The SLBs are very similar to collateralized loans.

Note 2: See the joint Policy Note No. 386 (2009) of the People’s Bank of China and the CBRC. The overcapacity industries are designated by the State Council and include steel, electrolytic aluminum, coal, ships, cement, flat glass, fertilizer, polysilicon, wind power equipment, soybean crushing and large forgings.

Note 3: The authorities made major policy adjustments by delisting some industries from the overcapacity list on March 13, 2014.

(Jinfan Zhang is an Associate Professor at the School of Economics and Management, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen; Ting Yang is a Lecturer at the School of Economics and Management, North China University of Technology; Yanping Shi is a Professor at the School of International Trade and Economics, University of International Business and Economics.)

References

Adrian T., Ashcraft A.B. (2016). Shadow banking: A review of the literature. In: Jones G. (eds) Banking Crises. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137553799_29

Allen, F., Qian, Y., Tu, G. and Yu, F. (2019). Entrusted loans: A close look at China’s shadow banking system, Journal of Financial Economics 133, 18–41.

Chang, Jeffery (Jinfan), Ting Yang, Yanping Shi (2020). Finance leases: A hidden channel of China’s shadow banking system, Working paper.

Chen, K., Ren, J. and Zha, T. (2018). The nexus of monetary policy and shadow banking in China, American Economic Review 108, 3891–3936.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email