Capital Regulations, Bank Risk-Taking, and Monetary Policy in China

China implemented Basel III in 2013 and tightened bank capital regulations. Empirical evidence shows that the new regulations significantly reduced bank risk-taking following monetary policy easing. To meet the tightened capital requirements, banks respond to a balance-sheet expansion by raising the share of lending to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that are perceived as low-risk borrowers under government guarantees. We estimate that a one standard deviation positive shock to M2 growth raises the probability of SOE lending by up to 27%. Raising the share of SOE lending, however, reduces aggregate productivity, creating a trade-off between financial stability and allocative efficiency.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, central banks around the world have aggressively eased monetary policy to support their economies and the functioning of financial markets. These policy measures are arguably necessary to mitigate the recessionary effects of the pandemic in the short run. Over time, however, persistently low interest rates associated with monetary policy easing can fuel asset price booms, potentially leading to excessive leverage and risk-taking by financial institutions (for example, Bernanke 2020). Does monetary policy easing encourage risk-taking? If so, would tightening capital regulations help alleviate concerns about financial stability in periods with expansionary monetary policy?

In a recent paper (Li, et al. 2020), we examine how monetary policy shocks affect bank risk-taking using loan-level and firm-level data from China. We present robust evidence that, after China’s 2013 implementation of Basel III, which tightened bank capital regulations, banks responded to expansionary monetary policy shocks by raising the share of lending to low-risk firms and, in particular, to SOEs that receive high credit ratings under government guarantees. We argue that increases in the share of SOE lending lead to capital misallocation and reduce aggregate productivity, because SOEs are on average less productive than private firms. Thus, the tightened capital regulations introduced a monetary policy trade-off between financial stability and aggregative allocative efficiency.

Tightening Regulations Shifts Bank Lending to Low-Risk Borrowers

In China, bank lending is the primary source of financing for firms. Thus, changes in banking regulations can have important implications for the macro economy, and in particular, for the transmission of monetary policy.

In June 2012, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC)—China’s banking regulator—announced the implementation of the Basel III capital regulations for all 511 commercial banks in China, effective January 1, 2013. The new capital regulations raised the minimum capital adequacy ratio (CAR) to 10.5% (from 8%), and for systemically important banks, the minimum CAR was raised to 11.5%. The new capital regulations also introduced the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach to calculating risk-weighted assets for corporate loans based on the credit risks of loans.

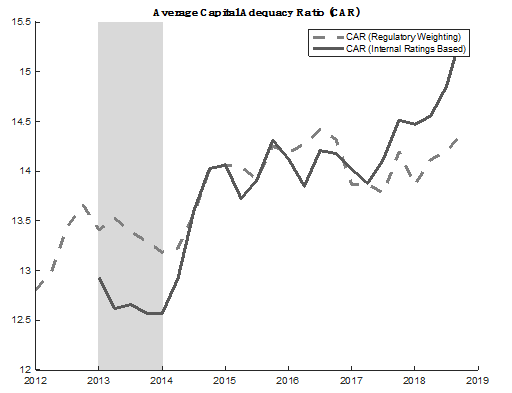

Figure 1 presents the average effective CAR for China’s Big Five banks, where the CAR is calculated using both the old definition (that is, the pre-Basel III definition, the dashed line) and the new definition (that is, the Basel III definition, the solid line). The gap between the two lines in 2013–2014 (in the shaded area) shows that the new regulations have tightened bank capital requirements: based on the new definition, the average effective CAR of the Big Five banks (the solid line) is lower than it was under pre-Basel III regulations (the dashed line).

Figure 1. Average Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) for China’s Big Five Banks

This figure presents the average effective CAR for China’s Big Five banks, including Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China, and Bank of Communications. The dashed line shows the CAR calculated using the pre-Basel III regulatory weighting (RW) approach. The solid line shows the CAR calculated based on the post-Basel III internal ratings-based (IRB) approach. Both CARs are the averages across the five banks.

Source: WIND and Li, et al. (2020).

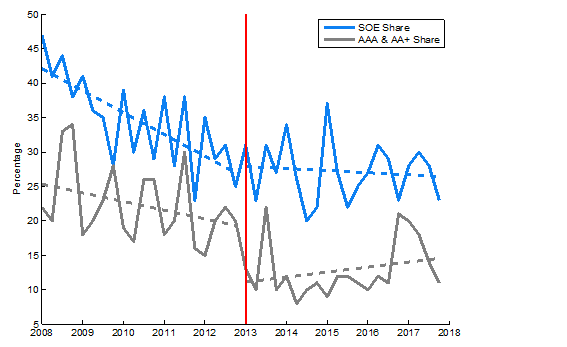

The tightened capital regulations induced a shift in bank lending toward low-risk borrowers, as shown in Figure 2. The figure shows that the share of high-quality loans (that is, those rated AA+ or AAA) has declined steadily from 2008 to 2012, partly reflecting the expansion of bank lending triggered by China’s large-scale fiscal stimulus package implemented during the global financial crisis. Since the implementation of Basel III in 2013, however, the share of high-quality loans has steadily increased. The figure also shows a similar pattern for the share of SOE loans, consistent with the evidence that SOE loans are positively correlated with high credit ratings.

Figure 2. The Share of High-Quality Loans (Rated AA+ or AAA) and SOE Loans

This figure shows the share of SOE loans (blue solid line) and the share of AAA and AA+ loans (the gray solid line) in the value of total loans. The dashed lines show linear fitted trends before and after 2013.

Source: Li, et al. (2020)

Tightening CAR Reduces Bank Risk-Taking Following Monetary Policy Expansion

To study how regulatory policy changes can affect the response of bank risk-taking to monetary policy shocks, we use confidential loan-level data from one of the Big Five commercial banks in China. To construct firm-level controls for empirical estimation, we merge the loan-level data with the firm-level data from China’s Annual Survey of Industrial Firms (ASIF) obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) of China. The ASIF sample contains about 4 million firm-year observations for the period from 1998 to 2013. We merge the two data sources by matching firm names and then use the merged data, with about 400,000 unique firm-loan pairs for the period from 2008 to 2017, to estimate the empirical impact of tightening capital regulations on the relation between bank risk-taking and monetary policy shocks. We measure monetary policy shocks by the exogenous component of the M2 growth rate estimated using the method developed by Chen et al. (2018).

We find that, after the tightening of capital regulations in 2013, a monetary policy expansion induces bank branches with high-risk exposures in the past to increase the share of lending to SOE firms, which are perceived as ex ante low-risk borrowers. The estimated declines in bank risk-taking following a monetary policy expansion are both statistically significant and economically important. Our baseline estimation suggests that a one standard deviation positive shock to M2 growth raises the probability of SOE lending by 6.8% after the new regulations were put in place in 2013.

When we further control for the level of capitalization in the regression, we estimate that the same monetary policy shock raises the probability of SOE lending by up to 27%. This finding suggests that the declines in bank risk-taking following monetary policy expansion in the post-2013 periods were primarily driven by changes in risk weighting, not changes in capitalization. A bank can meet tightened capital requirements by reducing the level of risk-weighted assets, and under the new risk-weighting approach (that is, the IRB approach), an effective way to reduce the level of risk-weighted assets is to increase the share of loans to de jure low-risk borrowers such as SOEs.

During the post-2013 period, China has implemented other structural reforms such as interest-rate liberalization (started in 2013 and deepened in 2015), deleveraging (in late 2015), and anti-corruption campaigns (started in late 2012). These policy changes might also affect bank risk-taking. We have examined the effects of these potential confounding factors. Our evidence suggests that, after controlling for those other factors, changes in capital regulations remain an important driving force of the observed changes in bank risk-taking behaviors.

Tradeoffs Between Financial Stability and Aggregate Productivity

Our empirical findings show that tightening capital regulations can effectively reduce bank risk-taking, both on average and conditional on monetary policy shocks. This evidence should alleviate financial-stability concerns associated with expansionary monetary policy. However, banks reduce risk-taking by raising the share of lending to SOEs, which have lower productivity on average than private firms (Hsieh and Klenow 2009). Thus, an increase in the share of lending to SOEs would reduce aggregate productivity.

Indeed, using provincial-level data, we find evidence that a positive monetary policy shock significantly reduces total factor productivity (TFP) after 2013, but not before. SOE loans receive high credit ratings and are perceived as low-risk loans under government guarantees. However, ex post, SOE loans are more likely to be non-performing or overdue than average. Thus, tightening capital regulations leads to a trade-off between financial stability and aggregate productivity.

Conclusion

The tightening of capital regulations under Basel III implemented in 2013 in China has significantly changed bank risk-taking behavior and its response to monetary policy shocks. Banks reduced risk-taking by increasing the share of lending to SOEs, both on average and conditional on monetary policy expansions. After 2013, a one standard deviation increase in the exogenous component of M2 growth raises the probability of SOE lending by up to 27%. Since SOEs have lower average productivity than private firms, increasing lending to SOEs reduces aggregate productivity. Our evidence suggests that tightening capital regulations can lead to a trade-off between financial stability and aggregate productivity.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Federal Reserve System.

(Xiaoming Li, Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance, China; Zheng Liu, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco; Yuchao Peng, Central University of Finance and Economics, China; Zhiwei Xu, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China.)

References

Bernanke, Ben S. 2020. “The New Tools of Monetary Policy.” American Economic Association Presidential Address.

Chen, Kaiji, Jue Ren, and Tao Zha. 2018. “The Nexus of Monetary Policy and Shadow Banking in China.” American Economic Review 108 (12), 3891–3936. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20170133.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Peter J. Klenow. 2009. “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (4), 1403–1448. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1403.

Li, Xiaoming, Zheng Liu, Yuchao Peng, and Zhiwei Xu. 2020. “Bank Risk-Taking and Monetary Policy Transmission: Evidence from China,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2020-27. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2020-27.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email