FDI and Firm Productivity in Host Countries: The Role of Financial Constraints

Using the Chinese firm-level data, we find that FDI firms may have even lower cutoff productivity than local firms, although FDI firms are still, on average, more productive than their local counterparts. In addition, these findings are more pronounced in financially more vulnerable sectors. We argue that easy access to international financial markets by FDI firms has played an important role in driving our empirical findings. We show in a two-country model that policies that do not properly recognize FDI firms’ financial advantages can be counterproductive.

Many emerging markets provide tax and other incentives to attract foreign direct investment (FDI); the policy is motivated by the belief that FDI can benefit host countries’ economic growth by introducing advanced technology and/or managerial skills from multinational companies (MNCs). Previous empirical studies document convincing evidence of technology transfers from FDI firms to local firms through technology diffusion, labor turnover, and other channels, (e.g., Javorcik 2004, Yasar and Paul 2007, Keller and Yeaple 2009, Alfaro and Chen 2013, and others). In this case, policies to attract FDI may improve host countries’ technology improvement and social welfare.

MNCs are usually also less financially constrained than local firms in emerging markets. Recent studies have examined this financial advantage and how it drives FDI flows and alleviates financial constraints in host countries (e.g., Wang and Wang 2015; Manova, Wei, and Zhang 2015; Desbordes and Wei 2017; Bilir, Chor, and Manova 2019; and Alquist et al. 2019, among others). In a recent paper, we show that FDI firms’ financial advantage has profound effects on the firm productivity in host countries and the effectiveness of FDI policies.

Using Chinese firm-level data between 2000 and 2007, we compare the productivity of FDI and local firms in China and document two interesting findings. As in other emerging markets, FDI firms in China are on average more productive than local firms in our data. However, if we rank FDI firms based on their productivity and do the same for local firms, we find that the FDI firms at the bottom of the ranking are even less productive than their counterparts among local firms. That is, FDI firms have lower cutoff productivity than local firms in our Chinese firm-level data. In addition, this finding is more pronounced in financially more vulnerable sectors.

We employ five measures for financial vulnerability at the sector level, following Manova, Wei, and Zhang (2015). These five measures are not highly correlated, indicating that they capture conceptionally different dimensions of financial vulnerability. Following Manova Wei, and Zhang (2015), we calculate the first principal component (FPC) of the five indicators and use it as our preferred proxy for the sector’s financial vulnerability. The underlying five measures are calculated from the data on all publicly traded U.S.-based firms to ensure that the financial vulnerability measures are not endogenously determined by China’s level of financial development. Indeed, these measures are intended to capture features inherent in the manufacturing process, which remain the same across countries and are beyond the control of individual firms.

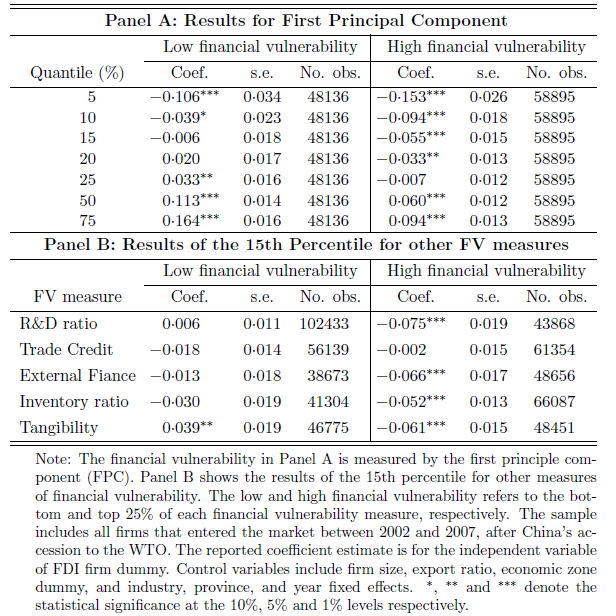

For firms in the low and high financial vulnerability sectors (bottom 25% and top 25% under our financial vulnerability measures), we regress firm productivity on an FDI dummy and other control variables. Table 1 reports the coefficient estimates of the FDI dummy in our quantile regressions. A negative coefficient estimate indicates that FDI firms have lower productivity than local firms after controlling for other factors that may affect firm productivity. Panel A presents the results for FPC and Panel B displays the results for other financial vulnerability measures. In the high financial vulnerability sector (top 25% of FPC), we find that the coefficient estimate of the FDI dummy is significantly negative (at the 5% or 1% significance level) for firms at the bottom 20% of productivity (e.g., quantiles of 20%, 15%, 10%, and 5%), indicating that FDI firms in these quantiles have even lower productivity than local firms. In contrast, the evidence for the low financial vulnerability sector (bottom 25% of FPC) is much weaker.

Panel B reports the results of the 15th percentile for the other five measures of financial vulnerability that underlie the FPC. In four of these five measures, the coefficient estimate of the FDI dummy is significantly negative in the high financial vulnerability sector, but not in the low financial vulnerability sector. At the 15th percentile, the productivity of FDI firms is about 6% lower than that of local firms in the sectors of high financial vulnerability under various measures of financial vulnerability.

Table 1: Results of Quantile Regressions

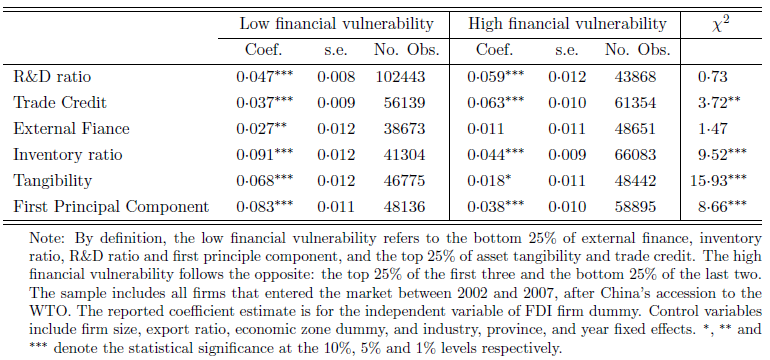

FDI firms are still on average more productive than local firms in our data, as shown in the OLS regression results of Table 2. The coefficient estimate of the FDI dummy is positive for both low and high financial vulnerability sectors, although the productivity advantage of FDI firms is weaker in the high financial vulnerability sector.

Table 2: Results of OLS Regressions

Standard FDI models in the literature cannot replicate our empirical findings. Melitz-type models with heterogeneous firms (e.g., Helpman, Melitz, and Yeaple 2004) are usually employed to study FDI firms in the literature. In these models, FDI firms face higher fixed production costs than local firms, reflecting the fact that FDI firms operate in a foreign country and have various disadvantages relative to their local counterparts. The higher fixed production costs prevent FDI firms of low productivity from entering the market. Therefore, FDI firms in such models have both higher cutoff and average productivity than local firms and their productivity advantage is unchanged with sectoral financial vulnerability.

We argue that the financial advantage of FDI firms may have played an important role in our empirical findings. FDI firms usually pay lower financial costs than local firms because of their easy access to international capital markets. Wang and Wang (2015) and Alquist et al. (2019) show empirically that this financial advantage of FDI firms is an important factor in driving foreign mergers and acquisitions in emerging markets. Motivated by these empirical findings, we modify the standard model to incorporate financial frictions for local firms, to capture the fact that FDI firms are usually less financially constrained than local firms in emerging markets. As a result, local firms must pay higher financial costs than FDI firms, while they face lower fixed production costs than FDI firms. Although high fixed production costs allow only very productive FDI firms to enter the market and compete with local firms, the financial advantages of MNCs work in the opposite direction. In this case, the relative cutoff productivity of FDI firms to local firms will depend on which of the above effects dominates.

We show in the model that if FDI firms’ financial advantage is large enough, they could have lower cutoff productivity than local firms. FDI firms may still have higher average productivity than local firms because MNCs have a fatter tail in their productivity distribution, as documented in previous studies. FDI firms’ financial advantages are expected to be stronger in financially more vulnerable sectors. For instance, in the sectors that are more dependent on external finance, FDI firms’ financial advantage is more likely to dominate their disadvantage of fixed production costs. In these sectors, FDI firms are more likely to have lower cutoff productivity than local firms.

To further explore the policy implications of our findings, we construct a two-country model to study the effects of FDI tax policies and financial market reform on aggregate productivity and welfare in the host country when FDI firms have financial advantages over local ones. In our model, FDI firms are on average more productive than local firms in the host country, but have lower cutoff productivity than the local firms due to financial frictions in the host country. We show that the host country's welfare is determined by the aggregate productivity of FDI and local firms, the product varieties available to the households, and the transfers from the government to households in the host country.

We first calibrate the tax rates to match the FDI tax policies in China, under which FDI firms pay lower corporate and value added taxes than local firms. Then, we remove the tax benefits of FDI firms while the total government revenues (and transfers to the household) are kept constant. In our benchmark model, the average productivity of local firms and FDI firms in the host country displays a humped shape: it first increases when we raise the tax rate of FDI firms as the cutoff productivity of FDI firms rises with the tax rate. This finding suggests that tax benefits offered to FDI firms actually reduce average firm productivity in the host country because such policies attract FDI firms that have even lower productivity than local firms, which is exactly the opposite of the purpose of such policies. Of course, average productivity and welfare decrease when the host country taxes FDI firms too heavily because high-productivity FDI firms may exit the host country if the tax rate is too high.

If we interpret taxes broadly as barriers to FDI, our findings highlight the trade-off in determining restrictions/subsidies for FDI firms in countries with underdeveloped financial markets. On the one hand, emerging markets should remove barriers and even provide additional incentives for high-productivity FDI firms to enter. On the other hand, low-productivity firms may take advantage of the universal subsidies offered to FDI firms, which decreases the aggregate productivity and welfare of host countries. This is particularly problematic when FDI firms have lower cutoff productivity than local firms because of their financial advantages. Faced with this problem, many emerging markets, including China, have adopted policies to ensure that FDI firms introduce advanced technology and management skills to their countries. For instance, China employed performance requirements to control for the quality of FDI firms and some tax exemptions were provided only to FDI firms that met certain performance requirements before China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 (see Note 1).

We also find that financial market improvement may have to be combined with tax reforms to increase the host country’s welfare. The improvement of financial market efficiency reduces the disadvantages of local firms relative to FDI firms. As a result, local firms with lower productivity can enter the market when the host country’s financial market becomes more efficient. It reduces average productivity in the host country, but increases its product varieties. The overall welfare effect depends on which effect dominates. We show that distortionary taxes imposed to finance FDI subsidies in the host country can repress the increase in product varieties, such that its welfare decreases when financial market efficiency improves.

Note 1: China had to abandon the policy of performance requirements after 2001 to meet WTO regulations.

(Wontae Han is a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Management and Economics at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen; Jian Wang is an Associate Professor of Economics at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen; Xiao Wang is a Professor in the School of Management and an Assistant Dean of International Institute of Finance at the University of Science and Technology of China.)

References

Alfaro, Laura, and Maggie X. Chen. 2013. “Market Reallocation and Knowledge Spillover: The Gains from Multinational Production.” Working Papers 2013–17, George Washington University, Institute for International Economic Policy. https://www2.gwu.edu/~iiep/assets/docs/papers/ChenIIEPWP201317.pdf.

Alquist, Ron, Nicolas Berman, Rahul Mukherjee, and Linda Tesar. 2019. “Financial Constraints, Institutions, and Foreign Ownership.” Journal of International Economics 118: 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2019.01.008.

Bilir, L. Kamran, Davin Chor, and Kalina Manova. 2019. “Host-Country Financial Development and Multinational Activity.” European Economic Review 115: 192–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.02.008.

Desbordes, Rodolphe, and Shang-Jin Wei. 2017. “Foreign Direct Investment and External Financing Conditions: Evidence from Normal and Crisis Times.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 119 (4): 1129–1166. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12192.

Helpman, Elhanan, Marc J. Melitz, and Stephen R. Yeaple. 2004. “Export Versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms.” American Economic Review 94 (1), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282804322970814.

Keller, Wolfgang, and Stephen R. Yeaple. 2009. “Multinational Enterprises, International Trade, and Productivity Growth: Firm-Level Evidence from the United States.” Review of Economics and Statistics 91 (4): 821–31. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.399741.

Manova, Kalina, Shang-Jin Wei, and Zhiwei Zhang. 2015. “Firm Exports and Multinational Activity Under Credit Constraints.” Review of Economics and Statistics 97 (3): 574–88. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1534905.

Smarzynska Javorcik, Beata. 2004. “Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers through Backward Linkages.” American Economic Review 94 (3): 605–27. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041464605.

Wang, Jian, and Xiao Wang. 2015. “Benefits of Foreign Ownership: Evidence from Foreign Direct Investment in China.” Journal of International Economics 97 (2): 325–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.07.006.

Yasar, Mahmut, and Catherine J. Morrison Paul. 2007. “International Linkages and Productivity at the Plant Level: Foreign Direct Investment, Exports, Imports, and Licensing.” Journal of International Economics 71 (2): 373–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2006.03.004.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email