Good Finance, Bad Finance, and Resource Misallocation: Evidence from China

Using city-level data from China, we find that the overall size of finance does not affect the extent of resource misallocation. However, when finance is decomposed into different parts, we find that local government-driven finance backed by revenues from land sales exacerbates the misallocation problem, while the remaining part of finance, which is more likely market-driven, significantly improves allocative efficiency. Further evidence shows that local government-driven finance lowers allocative efficiency by facilitating the allocation of resources to the low-productivity state sector, but nonlocal government-driven finance reduces the extent of such distortions.

Resource misallocation has long been an important issue in economic studies, and the lack of finance has been singled out as one potential source causing allocative inefficiency across countries, regions, industries, and firms. In the literature of financial economics, a prevailing measure of financial development is the quantity of financial assets to GDP. However, economists and policymakers are interested not only in the amount of savings transferred to borrowers, but also in the efficiency with which the financial resources are used. Nowadays, the rapid growth of scale in the global financial system has brought about more finance, but not necessarily better finance since not all aspects of financial development support improved allocative efficiency in the real economy. Therefore, disentangling the sources of financial assets that improve allocative efficiency from those failing to do so is important to fully understand the virtues of finance.

China has a unique institutional background for the investigation of how different aspects of financial development affect resource misallocation. Following the transition from a planned economy to a market-oriented one, the central government used political tournaments based on economic performance to motivate local governments to promote local economic growth. Under such an institutional arrangement, GDP growth is a key performance indicator (e.g., Qian and Xu 1993; Maskin, Qian, and Xu 2000; Li and Zhou 2005). While local governments have strong incentives to grow their local economies through investments, they face inadequate fiscal revenues, especially after the tax-sharing reform in 1994, and so must look for off-budget sources of capital. In 1998, the amended Land Administration Law created huge windfalls for local governments (Chen and Kung 2016), allowing governments at or above the county level to keep revenues from land sales under their jurisdictions. To raise funds, local governments can transfer the use rights of existing urban land to firms, or they can first convert collectively owned rural land into new urban land by compensating rural collectives in exchange for their land ownership and then transfer the converted land to its users at a higher price. As the de jure controllers of urban land, local governments have strong incentives to liquidate the land in their jurisdictions within the quotas set by the State Council. Shortly after 1998, revenues from land sales become a major off-budget source of revenues for local governments.

Land sales not only ease budget constraints for local governments, but also exert significant impacts on the finance sector. Specifically, land sales increase the extent to which the finance sector is biased toward the state sector. Since the financial system in China is dominated by the banking sector, firms possessing land as collateral can more easily access financial resources. Due either to pressure in performance-based political tournaments or to corruption (Cai, Henderson, and Zhang 2013), local governments might allocate excessive land resources to firms with political connections, such as local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and other local state-owned enterprises. Thus, while driving up the overall size of financial assets, land sales by local governments increase the inequality between the state and non-state sectors.

In a recent paper (Deng and Liu 2024), we hypothesize that in the Chinese institutional context, local government-driven finance (LGDF) lowers the allocative efficiency of resources for two reasons. First, this part of finance is largely used to resolve local governments’ fiscal inadequacy, which is need-based rather than efficiency-driven. Second, this part of finance is indicative of how economically active a local government is. As Liu and Siu (2011) document, the return on invested capital (ROIC) for state-sector investment is lower on average than that for non-state-sector investments. After the part of finance driven by local governments is excluded from the financial system, what is left is likely market-driven and may help facilitate the allocation of resources to high-productivity firms. The part of finance orthogonal to local government-driven finance, which we term nonlocal government-driven finance (NLGDF), is expected to improve the efficiency of resource allocation. In our paper, we do not consider the spillover effect of local government-driven finance on the supply of public goods such as sound infrastructure. However, we exclude public utilities from our empirical analyses and keep only manufacturing firms in our sample, which should mitigate the concern about the spillover effect.

Empirically, we use a regression-based approach to estimate LGDF at the city level. As most debts related to local governments are backed by revenues from land sales as collateral, we estimate LGDF to be a function of the revenues from land sales. We regress Finance (the city-level ratio of the outstanding value of financial assets to local GDP) against Land Sales (the city-level ratio of the accumulative revenues from land sales to local GDP) through a linear model, finding that when revenues from land sales increase by one RMB, the value of financial assets increases by RMB1.884 on average. We also regress Finance against Land Sales and its squared term, cubic term, and quartic term, but the results do not support a significant nonlinear relationship between land sales and finance. We therefore set LGDF to be proportional to the revenues from land sales, that is, LGDF =1.884 × Land Sales. In addition, NLGDF = Finance – LGDF. Then, we construct a city-level measure of resource misallocation by extending the model in Hsieh and Klenow (2009). In the presence of distortions, capital and labor cannot be used efficiently, so the resulting aggregate output is lower than the efficient aggregate output, which is defined as the potential maximum output given firms’ production technologies and the total amount of resources available. We define Misallocation for each city each year as one minus the ratio of the actual aggregate output to the efficient aggregate output.

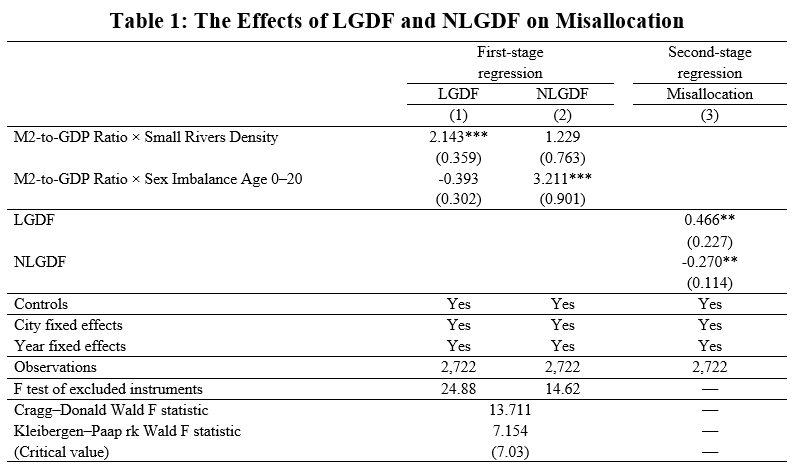

To identify the causal effects of LGDF and NLGDF on resource misallocation, we use the instrumental variable (IV) approach. We instrument LGDF using the interaction of M2-to-GDP Ratio (the ratio of money supply to GDP at the national level) and Small Rivers Density (the total length of small rivers divided by city area). Constructed on exogenous geographic conditions, Small Rivers Density predicts the intensity of political tournaments because cities with a higher density of small rivers tend to have more administrative units and hence more local officials as political competitors of each other. Besides, we instrument NLGDF using the interaction of M2-to-GDP Ratio and Sex Imbalance Age 0–20 (the male-to-female ratio under age 20). In China, the sex imbalance after the enforcement of the one-child policy can be largely due to the long tradition of son preference, which should be exogenous to resource misallocation. As documented by Wei and Zhang (2011), families with sons have stronger savings motives because of the desire to improve their relative standing in the marriage market. Thus, cities with a higher male-to-female ratio in the premarital age cohort should have more competitive savings, which can translate into more financial assets unrelated to the behaviors of local governments. When constructing the IVs for LGDF and NLGDF, we interact M2-to-GDP Ratio with Small Rivers Density and Sex Imbalance Age 0–20 to ensure that the effects of Small Rivers Density and Sex Imbalance Age 0–20 on resource misallocation are driven through the channels related to finance (i.e., monetary policies).

The IV estimation shows that local government-driven finance and nonlocal government-driven finance exert significant but opposite effects on resource misallocation (see Table 1). If LGDF in a city is increased by one standard deviation (0.131), the extent of resource misallocation increases by 0.061, representing a 10.7% increase from the mean level (0.569). On the contrary, if NLGDF in a city is increased by one standard deviation (0.585), the extent of resource misallocation decreases by 0.158, representing a 27.8% decrease from the mean level. Furthermore, we find that local government-driven finance lowers allocative efficiency by facilitating the allocation of resources to the low-productivity state sector. Nonlocal government-driven finance, however, reduces the extent of such distortions.

Recently, a number of studies investigate the pitfalls of the modern financial system such as high leverage, expensive financial intermediation, and too-big-to-fail institutions. A fast-growing (both in size and sophistication) yet ill-functioning financial system may restrict credit mobility, distort credit allocation, and lead to socially unproductive uses of resources. We suggest that a socially productive approach to developing finance is to allocate credit to firms with the best entrepreneurial ideas and abilities, but not to those having more political connections and/or clout. Our study also provides policy implications on government debts. Nowadays, governments in many countries are relying on excessive credit supply to cope with the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Policymakers should be aware that although government-driven finance can improve financial depth in the short run, it may exert negative impacts on allocative efficiency and bring about long-term economic loss.

Notes: The sample coves 312 unique cities during 1999–2007. Robust standard errors clustered at the city level are reported in parentheses under estimated coefficients. ***, **, and * represent significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

(Jiapin Deng,Lingnan College, Sun Yat-sen University;

Qiao Liu,Guanghua School of Management, Peking University)

References

Cai, Hongbin, J. Vernon Henderson, and Qinghua Zhang. 2013. “China’s Land Market Auctions: Evidence of Corruption?” Rand Journal of Economics 44 (3): 488–521. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43186429.

Chen, Ting, and James Kai-sing Kung. 2016. “Do Land Revenue Windfalls Create a Political Resource Curse? Evidence from China.” Journal of Development Economics 123: 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.08.005.

Deng, Jiapin, and Qiao Liu. 2024. “Good Finance, Bad Finance, and Resource Misallocation: Evidence from China.” Journal of Banking and Finance 159: 107078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2023.107078.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Peter J. Klenow. 2009. “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (4): 1403–48. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1403.

Li, Hongbin, and Li-An Zhou. 2005. “Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China.” Journal of Public Economics 89 (9–10): 1743–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009.

Liu, Qiao, and Alan Siu. 2011. “Institutions and Corporate Investment: Evidence from Investment-Implied Return on Capital in China.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46 (6): 1831–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109011000494.

Maskin, Eric, Yingyi Qian, and Chenggang Xu. 2000. “Incentives, Information, and Organizational Form.” Review of Economic Studies 67 (2): 359–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-937X.00135.

Qian, Yingyi, and Chenggang Xu. 1993. “Why China’s Economic Reforms Differ: The M-Form Hierarchy and Entry/Expansion of the Non-State Sector.” Economics of Transition and Institutional Change 1 (2): 135–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.1993.tb00077.x.

Wei, Shang-Jin, and Xiaobo Zhang. 2011. “The Competitive Saving Motive: Evidence from Rising Sex Ratios and Savings Rates in China.” Journal of Political Economy 119 (3): 511–64. https://doi.org/10.1086/660887.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email