Anatomy of the CNH-CNY Peg: The Crucial Role of Liquidity Policies

Changes in the exchange rate between the offshore yuan (CNH) and onshore yuan (CNY) smooth out movements in the CNY-US dollar exchange rate, but they also strain Chinese capital controls. Authorities must carefully manage this exchange rate to keep the yuan growing internationally. They do so using not only monetary policies, but also especially liquidity policies that affect banks’ ability to create CNH deposits.

China’s two parallel currencies are pegged to parity. The CNY, used on the mainland, and the CNH, used offshore, can be officially exchanged one to one. However, Chinese capital controls are partly enforced by restricting the exchange of CNH for CNY. By controlling how much CNH Chinese nationals can get their hands on, authorities control how much they can save abroad. By controlling how much CNY foreign agents have access to, authorities control which Chinese assets are held abroad.

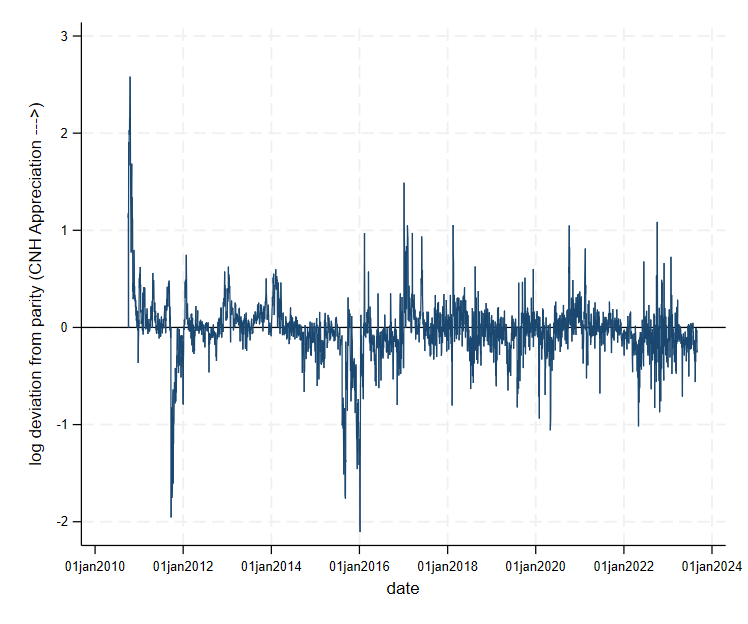

These restrictions in exchanging the two currencies imply that there is a market exchange rate between the two that deviates from one (Figure 1). If that deviation was too high, or too persistent, Chinese firms and banks would try to exchange the currencies through the official vehicles, and reverse that exchange in the market, to make an arbitrage profit. This puts pressure on the exchange restrictions and could ultimately cause the capital controls to fail (Liu, Sheng, and Wang 2020). Therefore, CNH monetary policy is subordinated to a single goal: to keep these deviations from parity small and short-lived.

Figure 1. Exchange rate of CNY-CNH, October 2010–August 2023

Source: Bahaj and Reis (2024a), The Anatomy of a Peg: Lessons from China’s Parallel Currencies.

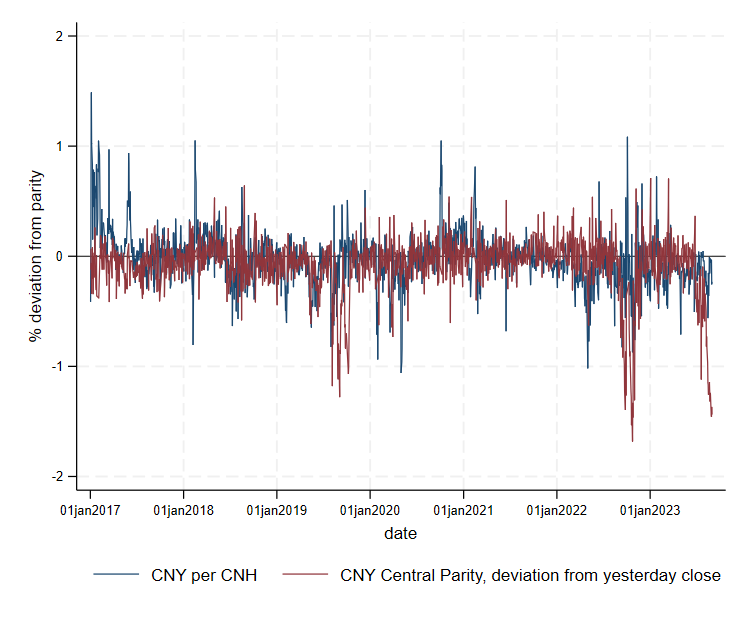

At the same time, allowing the CNY-CNH exchange rate to deviate from one temporarily can be (and has been) used as an escape valve for fluctuations of the yuan relative to the US dollar (USD) and other foreign currencies. Whenever the yuan is depreciating, by letting the CNH depreciate relative to the CNY, authorities can reduce the respective depreciation of the CNY relative to the USD. Because the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has an explicit policy of smoothing fluctuations in the yuan exchange rate using a managed trading band (Jermann, Wei, and Yue 2017), employing CNH monetary policy to assist in that goal is a powerful automatic mechanism for foreign exchange intervention. In fact, in the data, there is a strong negative correlation between the CNY-CNH exchange rate and the deviation of the CNY-USD exchange rate from the center of the PBoC’s trading band (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Log deviation between the CNY-USD central parity rate today and the CNY-USD exchange rate yesterday together with the log CNY-CNH exchange rate today.

Source: Bahaj and Reis (2024a), The Anatomy of a Peg: Lessons from China’s Parallel Currencies.

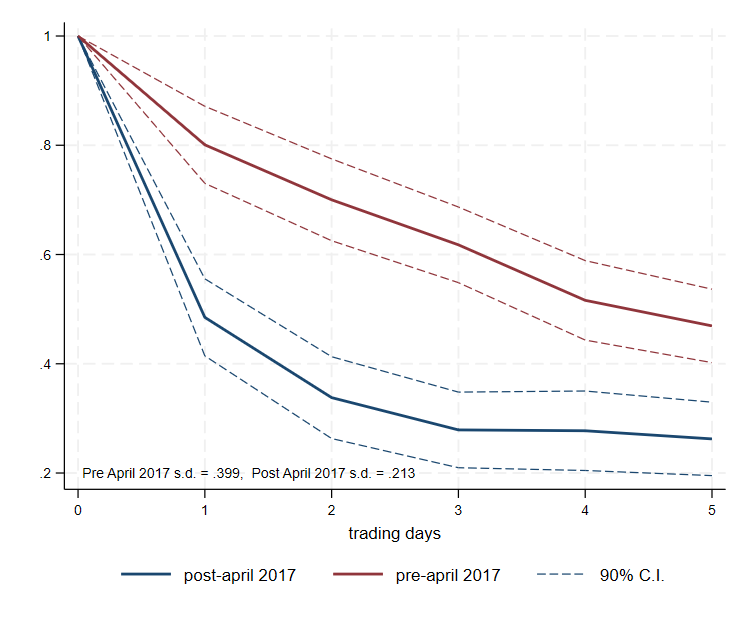

Figure 3 shows the success of this strategy, especially since April 2017, when the key features of the monetary and liquidity framework for CNH were put in place. Since then, the daily standard deviation of the CNY-CNH exchange rate has been 21bp, and the half-life of deviations from parity is less than one day.

How have the authorities achieved such success? After all, pegs between currencies usually fail, and parallel currencies appear in textbooks usually only as examples of how they are doomed to fail.

In Bahaj and Reis (2024a) we provide an anatomy of this peg. We exploit the peculiarities of the CNH-CNY framework as a rare opportunity to identify both shocks to the demand for CNH money as well as shocks to its supply (Bahaj and Reis 2024b discuss the money supply shocks).

Figure 3. Daily auto-correlogram of the log CNY-CNH exchange rate between October 2010 and March 2017 in red, and between April 2017 and May 2023 in blue.

Source: Bahaj and Reis (2024a), The Anatomy of a Peg: Lessons from China’s Parallel Currencies.

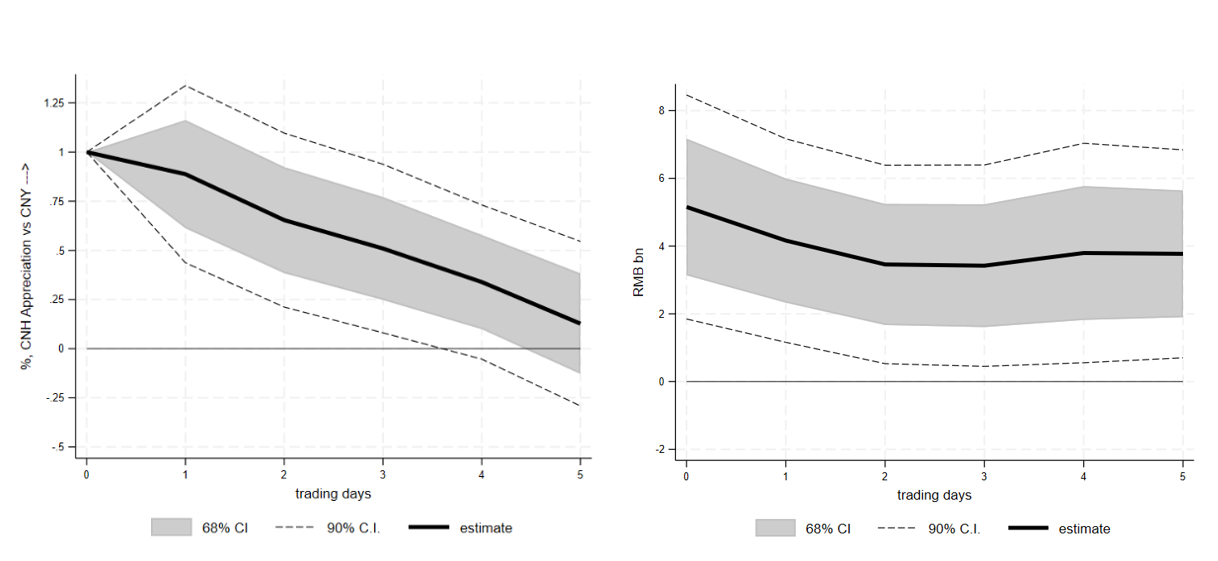

We estimate that five days after a money demand shock that appreciated the exchange rate by 100 basis points, this exchange rate had depreciated by 83bp re-establishing the peg (Figure 4, left panel). Of these, 53bp come from either the initial transitory shock to money demand dissipating, or by the movement of the exchange rate of the yuan with foreign currencies, like the US dollar. The remaining 30bp are brought about by purposeful policy.

We first estimate the monetary policy rule in response to fluctuations in the exchange rate. When the CNH appreciates by 100bp, we find that the supply of money rises by ¥5bn (Figure 4, right panel). In turn, using exogenous changes in the supply of money that followed changes in the operational procedures of the PBoC, we estimate that an increase in the supply of money by 1bn depreciates the exchange rate by 1bp. Combining the two estimates, monetary policy explains 5bp of the 30bp movement that re-established the peg.

Where do the other five-sixths come from? Liquidity policies. The CNH supply of reserves is not ample, or abundant, like in the US or the Euro Area. Rather, CNH reserves are kept scarce. This means there is a significant marginal benefit to extra liquidity. Banks trade for this liquidity in interbank markets, charging each other an interbank rate that is well above the interest on CNH reserves (which is zero). Often, they find themselves at the discount window-like CNH lending facilities operated by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA).

Figure 4. Response of the CNH-CNY exchange rate (left panel) and of the money supply (right panel) to a shock to the demand for CNH money

Source: Bahaj and Reis (2024a), The Anatomy of a Peg: Lessons from China’s Parallel Currencies.

When the demand for CNH money rises and its exchange rate appreciates, we see the impact on the marginal benefit of liquidity. The interbank interest rate rises and banks bid less for CNH bills as liquidity is more valuable. Drawings from the discount window go up.

The other side of the coin of this response of liquidity variables to the exchange rate is that liquidity policies that shift the marginal benefit of liquidity for banks can themselves affect the exchange rate. For one, the PBoC or the HKMA can loosen reserve requirements in CNH. Alternatively, the HKMA can lower the costs of its lending facilities or make it easier to access them. Both lower the marginal benefit of liquidity and depreciate the exchange rate toward parity after a money demand shock.

We have direct evidence that these channels work. When the HKMA in 2016 changed the charges of its lending facilities to a premium over an average of the last three days’ overnight interbank rates, it created a correlation between the interbank rate three days prior and the CNY-CNH exchange rate today that did not exist beforehand. Or when, in 2022, the HKMA cut the premium it charged, over the next ten trading days the CNH depreciated on average by 2bp relative to the CNY.

There are more extreme examples of these liquidity policies in the data. In 2015–16, the depreciation of the yuan relative to the US dollar led to a persistent gap between CNH and CNY (the escape valve). The authorities responded in part by tightening the flows that banks could make between their CNY and CNH reserves and CNH deposits fell by 20 log points relative to CNY deposits. Three-month CNH interbank rates spiked by more than 700 basis points above CNY rates. Parity between the parallel currencies was re-established. At the same time, by making CNH so scarce to raise its marginal benefit, authorities put a large dent in the internationalization of the yuan, which entered a period of stagnation, halting the rapid growth of the years before.

In August 2023 the yuan was depreciating again, and the escape valve again meant a deviation from parity. But now, authorities responded with a deft and surgical liquidity policy. The PBoC increased the supply of CNH bills, therefore absorbing CNH money. State banks changed their holdings of CNH reserves, acting as a helicopter vacuum of liquidity. The HKMA liquidity facility allowed the interbank rate to rise more moderately by only 200 bp relative to CNY. All combined, the peg held, the pressure eased, and the side effects on the role of the yuan were moderate, if any.

To conclude, an anatomy of the CNH-CNY peg confirms the classic monetary lesson: to keep a peg a central bank must be ready to increase the money supply when the exchange rate appreciates. At the same time, this experience shows that liquidity policies, like the regulation of reserves, the ability to shift liquidity, and the availability of lending facilities, are just as important, or more so.

Since 2017, Chinese authorities have set up an institutional framework to jointly manage both, which we describe in Bahaj and Reis (2024a). So far, they have succeeded. As the yuan is currently under pressure to devalue again (and the escape valve is showing with CNH trading below CNY), the system is under test once more. Our research points to the menu of policies that authorities can use and what their effects will be. If they succeed, this work tentatively suggests that the international use of the yuan can keep rising.

References

Bahaj, Saleem, and Ricardo Reis. 2024a. “The Anatomy of a Peg: Lessons from China’s Parallel Currencies.” Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. 18749. https://cepr.org/publications/dp18749.

Bahaj, Saleem, and Ricardo Reis. 2024b. “Interest Rates and Exchange Rates When the Money Supply Goes Up.” VoxEU, May 20, 2024. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/interest-rates-and-exchange-rates-when-money-supply-goes.

Jermann, Urban J., Bin Wei, and Vivian Zhanwei Yue. 2017. “The Two-Pillar Policy for the RMB from December 2015 to May 2017.” VoxChina, August 16, 2017. https://voxchina.org/show-3-34.html.

Liu, Renliang, Liugang Sheng, and Jian Wang. 2020. “Faking Trade for Capital Control Evasion: Evidence from Dual Exchange Rate Arbitrage in China.” VoxChina, November 25, 2020. https://voxchina.org/show-3-206.html.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email