China’s Health Insurance Evolution: Unpacking the Monumental Role of the NCMS

From 2003 to 2008, China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) provided health insurance to 800 million rural residents. We combined mortality data and household survey data to assess the program’s health impact and found that the NCMS significantly reduced overall mortality, saving over a million lives yearly at its peak. It also contributed to a 78% increase in China’s life expectancy during that time. We confirmed these findings with detailed data on individual health outcomes and healthcare utilization.

The global debate about health care insurance, particularly its significance in developing nations, remains relevant. Some emphasize the pivotal role of health care in improving the standard of living, while others delve deep into the intricacies of universal health coverage and its potential pitfalls.

One nation that captures the essence of this debate is China. Traditionally, developed nations have boasted vast insurance programs covering a majority of their populations. For instance, in 2018, among all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, out-of-pocket medical expenses accounted for only 20.1% of medical costs and 1.7% of income. Developing nations presented a starkly different scenario. In low-income countries, roughly 44.1% of medical expenses were borne directly by patients, amounting to 3.45% of income in 2018.

However, against the backdrop of rising medical costs, developing nations are showing a swift change. China, with its New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) launched in 2003, stands out prominently in this transformation.

The legacy of the NCMS

Launched in 2003 as a massive leap toward universal healthcare in China, the NCMS focused on providing comprehensive inpatient coverage to rural families. The scale of this initiative was staggering: within six years of its implementation, over 800 million individuals were covered, making it the largest medical insurance program in modern history.

Yet, despite its mammoth scale, the impact of the NCMS on health outcomes remained relatively uncharted. Notable papers including Lei and Lin (2009), Chen and Jin (2012), Cheng et al. (2015), and Zhou et al. (2017) found relatively weak health impacts of the NCMS. While the health impacts remain uncertain, other studies, such as Bai and Wu (2014), Liu (2016), Sun et al. (2009), and Wagstaff et al. (2009) suggest that the NCMS increases health care utilization and helps households cope with health-related financial shocks.

Disentangling the NCMS effect

In Gruber et al. (2023), we apply a sophisticated empirical framework to deal with the non-random adoption timing and time-varying trends across counties. Our approach leverages variations in agricultural density across counties as a source of variation, in addition to the staggered rollout of the program. It allows for comparisons between counties that adopted the NCMS at the same time but have different levels of agricultural density. We also include a rich set of fixed effects, such as county-fixed effects, province-by-year fixed effects, and an interaction of agricultural share with year fixed effects. We account for time-varying unobservable factors by incorporating county-specific linear trends and NCMS-timing-by-year fixed effects. This comprehensive approach ensures that the evaluation accounts for potential biases and provides a rigorous assessment of the program’s impact on health outcomes.

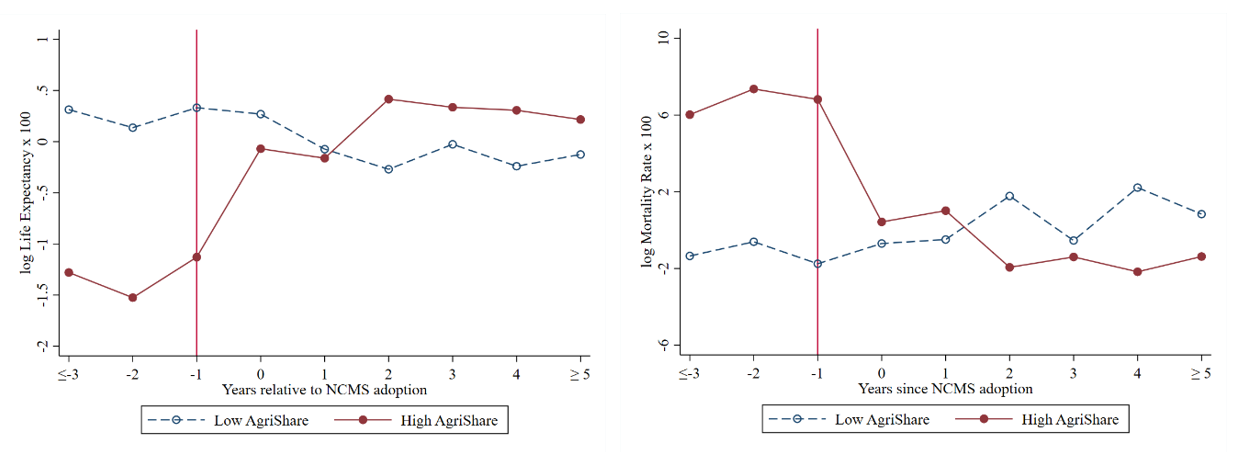

We combine aggregate county-level mortality data from the China Death Surveillance Point (DSP) Dataset with two individual survey datasets—the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey and China Health and Nutrition Survey—to conduct the analysis. In particular, the mortality rates and life expectancy are calculated using the recorded deaths and population counts from the DSP dataset, which includes a representative sample of counties. We found profound effects of the NCMS. Our main results, presented in Figure 1, use an event study to illustrate changes in mortality rates and life expectancy over time for counties above-median and below-median agricultural shares, respectively, after controlling for NCMS adoption time–specific and county-specific time effects. Before NCMS implementation, both groups exhibited similar and relatively stable trends: urban counties initially had an 8% lower mortality rate and a 1.5% longer life expectancy. However, after the implementation of the NCMS, the initial gaps narrowed and eventually reversed: rural counties had a 4% lower mortality rate and a 0.7% higher life expectancy. Such a reversal may suggest that, after the NCMS addresses the primary issue of health care accessibility in rural areas with initially poorer health conditions, these areas begin to outperform urban areas, which face higher health risks, such as increased pollution levels, stress, greater consumption of processed foods, and lifestyle-related chronic diseases.

(a) Age-adjusted mortality rates (b) Life expectancy at birth

Figure 1. Mortality rate and life expectancy around NCMS adoption: subsamples by agricultural share.

Notes: The figures plot the average value of the residuals from regressing mortality rate (a) and life expectancy (b) on NCMS-timing-by-year FE and county-specific linear trend. The regressions are weighted by county population. Counties in the sample are split by the median value of the share of the population with an agricultural Hukou. Observations more than three years (five years) before (after) the NCMS are binned into groups. The data is from the China Death Surveillance Point Dataset. The sample period is from 2004 to 2010.

A striking discovery was the estimated saving of over one million lives annually since 2008, a number surpassing the combined population of seven US states. Meanwhile, the cost per life saved was around 66,000 RMB (approx. 9,800 USD)—significantly lower than other metrics assessing the value of life.

These impressive results go beyond just numbers. We further find a broader improvement in the health care landscape, where the program has spurred measurable improvements in daily living activities, cognitive deficiencies, and self-assessed health statuses.

Deconstructing the mechanisms

Beyond the statistics, it is vital to understand the mechanisms driving these results. Two crucial mechanisms emerged from the study. Firstly, the reduced out-of-pocket expenses, particularly at the higher end of the expenditure distribution, alleviated personal worries about potential health care costs. This economic relief not only boosts health care usage, but also improves mental health and frees up resources for other essential consumptions, contributing to better health outcomes. Secondly, we found that increased health care provisions directly led to reduced mortality rates and extended life expectancies, explaining about 10% of the total health effects found.

A forward leap or a mere stepping stone?

While the NCMS reflects China’s commitment to health care reform, the broader question remains: how does this fit into the international narrative of health insurance?

China’s experience underscores the significance of well-structured insurance programs in enhancing health care outcomes. The NCMS, specifically with its inpatient focus, plays a pivotal role in China’s health care narrative. Given the country’s unique healthcare infrastructure, where hospitals play a central role in even mild and chronic care management, the widespread impact of the NCMS becomes even more pronounced.

However, while the NCMS may be shining beacon, it is essential to contextualize it within the broader health care discourse. Many developing nations still grapple with the basics of health care access, let alone universal insurance. Thus, while China’s story inspires, replicating it demands a nuanced understanding of local challenges and dynamics.

In conclusion, as nations strive for health care reform, the Chinese model serves as both an inspiration and a lesson. While the benefits of expansive insurance schemes like the NCMS are evident, the journey to universal health coverage is complex, demanding a harmonious blend of policy, infrastructure, and societal commitment.

References

Bai, Chong-en, and Binzhen Wu. 2014. “Health Insurance and Consumption: Evidence from China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme.” Journal of Comparative Economics 42 (2): 450–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2013.07.005.

Chen, Yuyu, and Ginger Zhe Jin. 2012. “Does Health Insurance Coverage Lead to Better Health and Educational Outcomes? Evidence from Rural China.” Journal of Health Economics 31 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.11.001.

Cheng, Lingguo, Hong Liu, Ye Zhang, Ke Shen, and Yi Zeng. 2015. “The Impact of Health Insurance on Health Outcomes and Spending of the Elderly: Evidence from China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme.” Health Economics 24 (6): 672–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3053.

Gruber, Jonathan, Mengyun Lin, and Junjian Yi. 2023. “The Largest Insurance Program in History: Saving One Million Lives per Year in China.” Journal of Public Economics 226: 104999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104999.

Lei, Xiaoyan, and Wanchuan Lin. 2009. “The New Cooperative Medical Scheme in Rural China: Does More Coverage Mean More Service and Better Health?” Health Economics 18 (S2): S25–S46. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1501.

Liu, Kai. 2016. “Insuring against Health Shocks: Health Insurance and Household Choices.” Journal of Health Economics 46: 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.002.

Sun, Xiaoyun, Sukhan Jackson, Gordon Carmichael, and Adrian C. Sleigh. 2009. “Catastrophic Medical Payment and Financial Protection in Rural China: Evidence from the New Cooperative Medical Scheme in Shandong Province.” Health Economics 18 (1): 103–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1346.

Wagstaff, Adam, Magnus Lindelow, Gao Jun, Xu Ling, and Qian Juncheng. 2009. “Extending Health Insurance to the Rural Population: An Impact Evaluation of China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme.” Journal of Health Economics 28 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.10.007.

Zhou, Maigeng, Shiwei Liu, M. Kate Bundorf, Karen Eggleston, and Sen Zhou. 2017. “Mortality in Rural China Declined as Health Insurance Coverage Increased, but No Evidence the Two Are Linked.” Health Affairs 36 (9): 1672–78. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0135.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email