Bonds of Love: Patriotism and the Rise of Modern Banks

This study illuminates the role of patriotism in banking development within the context of state formation, exploring the hypothesis that the initial trust vested in modern banks was a synergistic extension of the public’s patriotic sentiment. The cessation of Western financial support in World War I (1914) prompted China to rely on its domestic government bond market. Despite the new Republican government’s unproven creditworthiness, patriotic civilians subscribed to government bonds, which nurtured the rise of nascent official banks that underwrote these bonds. This trust in official banks gradually extended to private banks, fostering the development of the modern banking system. Our findings highlight that patriotism could be an alternative source of trust in government and financial institutions, particularly during challenging times.

Amid ongoing debates concerning the resilience of financial institutions, trust emerges as a critical factor for their stability and growth (Guiso et al. 2004). Understanding the origins of financial trust is therefore essential. While government endorsement typically bolsters financial trust—for instance, government backing is a common approach to mitigating financial instability such as bank runs—trust in government is not inherently stable. During challenging periods such as wars and revolutions, both government and bank credibility deteriorate. In Sun et al. (2024), we investigate the role of patriotism as a remedy for public trust (Depetris-Chauvin, Durante, and Campante 2020). Acting as a safeguard of last resort, patriotic sentiment ensures continued support for the government from the populace, and the reinforcement of government integrity, in turn, solidifies financial and economic stability.

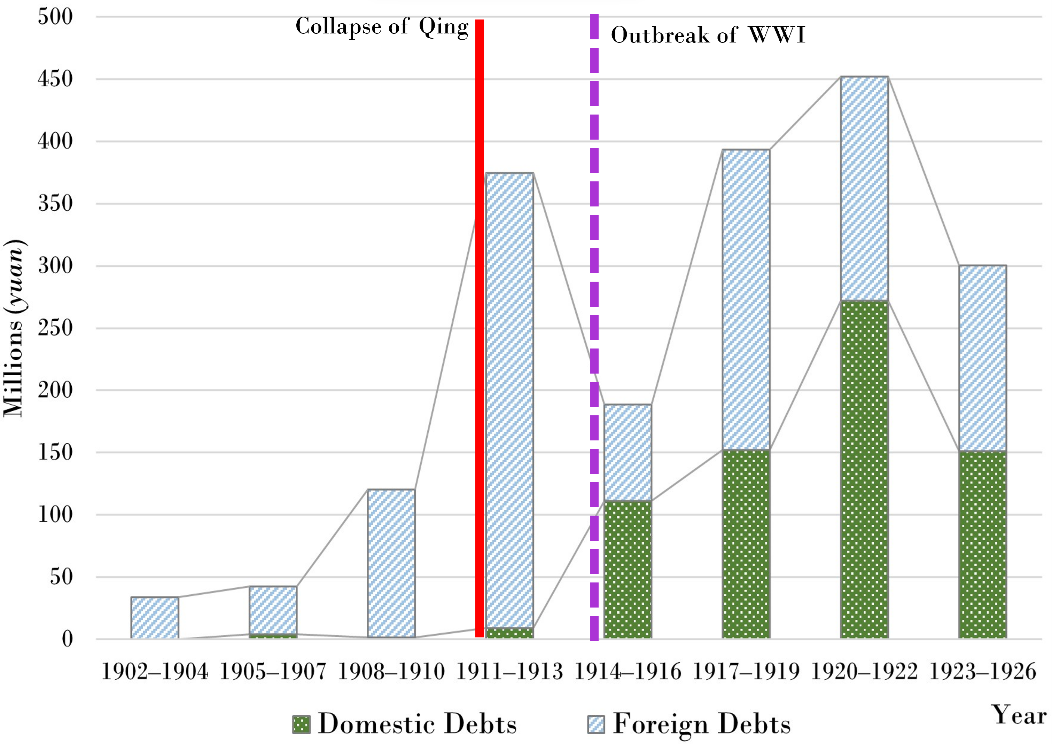

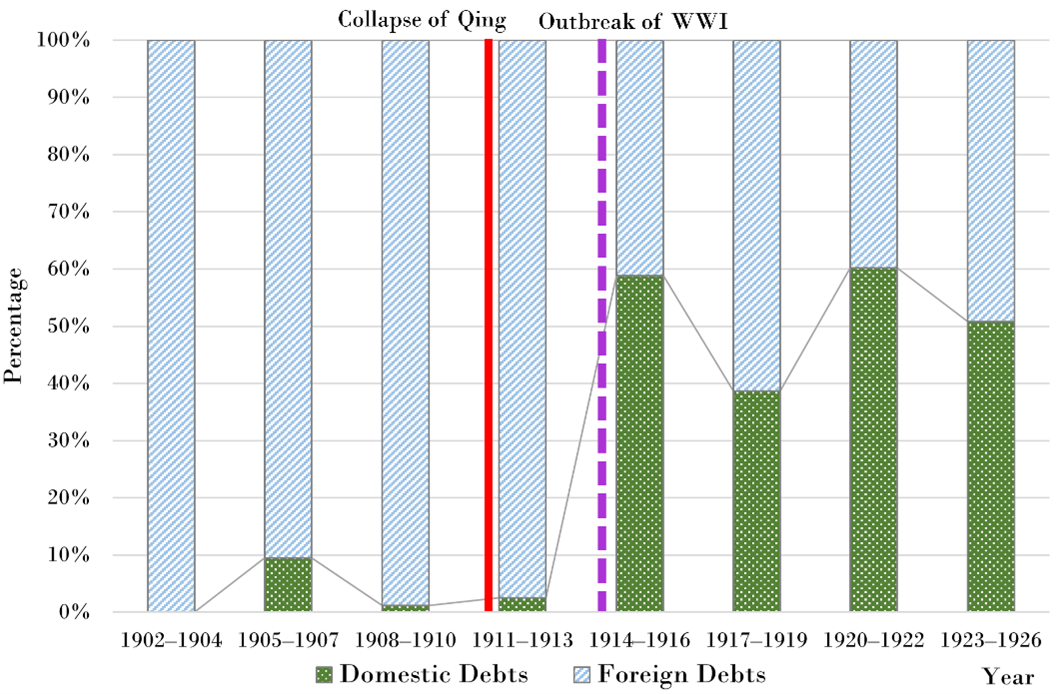

This paper leverages early 20th-century China to explore the hypothesis that the initial trust vested in modern banks was a synergistic extension of the public’s patriotic sentiment. Following its defeat in the Opium War in the 1840s, China underwent a forced opening to foreign powers, which introduced political instability. The Qing dynasty fell in 1911, leading to the transition into the Republican era (1912−1949). Both Qing and early Republican administrations faced significant capital shortages. Until the mid-1910s, Western nations and foreign banks had been the primary financiers of the Chinese government. However, with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Western countries, particularly those in European, withdrew a significant portion of their financial support. This external shift compelled the Republican government to seek capital from the domestic market by issuing government bonds. As depicted in Figure 1, foreign debts abruptly decreased in 1914, while domestic government debts significantly increased in both value and proportion thereafter.

Panel A. The collected amount of domestic and foreign debts

Panel B. The percentage share of domestic and foreign debts

Figure 1: Domestic and foreign debts (1902–1926)

Notes: The figures depict the collected amount (in million yuan) and percentage share of domestic and foreign debts in China from 1902 to 1926. Domestic debts refer to Chinese government bonds issued by the central government and 18 provincial governments. Foreign debts refer to debts borrowed by Chinese governments from foreign banks and foreign governments.

Rich historical anecdotes support the view that the rise of the domestic government bond market largely fueled the early growth of the Chinese modern banking system (Wu 1935). Modern banks, particularly official banks, significantly profited from underwriting and trading government bonds. They were also allowed to issue banknotes by using government bonds as collateral.

Amid the uncertainties of the time, what motivated the Chinese populace to subscribe to government bonds? Patriotic sentiment played a crucial role. Within the framework of social contract theory, the modern state is a mutual agreement between the civilians and the government, where the state provides protection and rights in exchange for civilians’ patriotic loyalty in the forms of financial contribution, such as tax compliance and government bonds subscription, and voluntary commitments, such as military service (Rousseau 1762, Besley 2020). Patriotic sentiment implies such a tacit agreement—a social contract—with the state, reflecting civilians’ willingness to support the government.

Inspired by social contract theory, we use the regional number of late Qing (1902–1911) unrest (minbian) involving resistance to tax as an ex ante measure of patriotism. The anti-tax unrest indicates a profound awareness of the contractual relationship between Chinese civilians and the Qing court, demonstrating a deep-seated belief in the rights of civilians to hold their government accountable. Regions showing stronger resistance to the Qing regime are indicative of a stronger desire to “tear up” the old social contract. We postulate that this shift also signifies readiness to engage in a new social contract, embracing the promise of patriotic participation in the state-building during the Republican era. Empirically, we find that anti-tax unrest in the late Qing were associated with increased civic engagement in the Republican era, as evidence by increased military participation in Baoding Military Academy, and increased establishment of associations promoting political ideologies and social welfare.

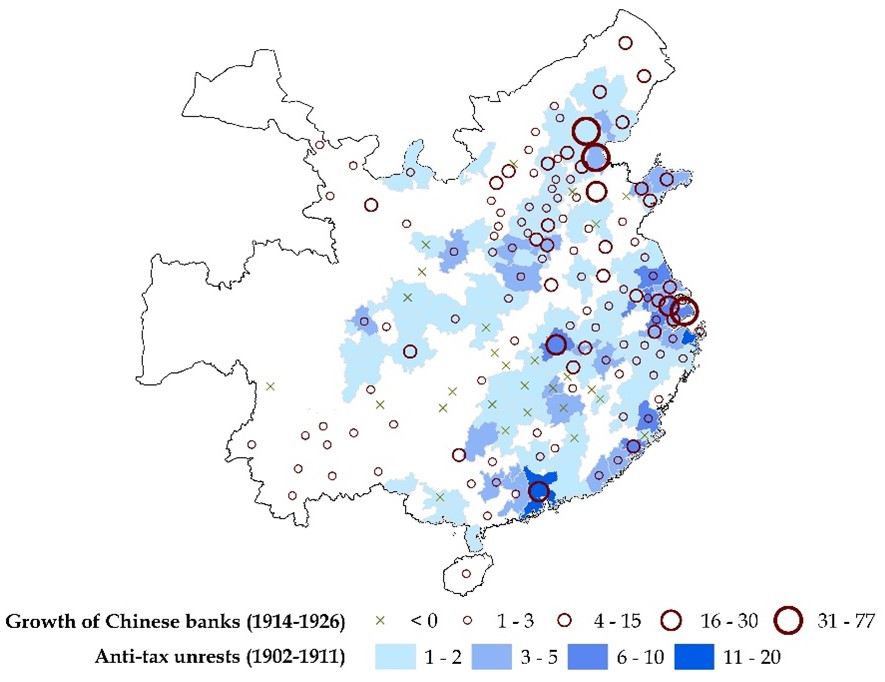

Based on a difference-in-differences (DiD) identification strategy, we find that regions with more frequent anti-tax unrest prior to 1912 collected significantly more money through issuing government bonds after the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The populace’s bond subscription was unlikely to be driven by investment incentives, as results remained largely unchanged after controlling for the local loan rate, a proxy for alternative investment returns. Consistently, more banks were established in these regions. Figure 2 depicts the overlap between anti-tax unrest and the growth of modern banks in China between 1915 and 1926.

Figure 2. Distribution of anti-tax unrest and growth modern banks (1915–1926)

Notes: The figure depicts the distribution of anti-tax unrest and the growth of modern banks. Anti-tax unrest refers to the total incidents of unrest involving tax resistance that occurred between 1902 and 1911 in each prefecture. Growth of modern banks refers to the difference in the number of banks between 1926 and 1915. The data are at the prefectural level. There are298 prefectures in the maps that cover China proper and exclude frontier regions that were administered outside the prefecture-county system for most or all of the Qing dynasty in 1911.

Despite the DiD identification strategy, one might argue that the endogeneity concerns still exist. It might be the case that regions with better economic foundations might expose their populations more to modern ideologies, leading to an increased awareness of civic rights and the subsequent flourishing of modern banks after the 1914 financial demand shock. To address this concern, we employ an instrumental variable (IV) approach using the occurrence of massacres during the founding period of the Qing Dynasty (1644−1661) as an instrument for anti-tax unrest in the late Qing (1902−1911). The brutal massacres were initiated by the Qing army to conquer China inland, significantly reducing the population from its peak during the Ming Dynasty (1368−1644). These historical events deeply impacted the collective memory, likely fostering long-standing dissatisfaction and mistrust of the government. Crucially, the exclusive condition is arguably satisfied because the early Qing massacres were exogenously determined by the marching routes of the Qing Army’s entry into inland China. Furthermore, these brutal events naturally led to the destruction of local economic conditions, which would not have been favorable to the development of banking. We posit that regions that experienced these massacres should show a higher propensity for anti-tax unrest, particularly when the central government’s control weakened. The results of the Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) analyses support our hypothesis, demonstrating a robust relationship between anti-tax unrest and banking development.

To further rule out alternative explanations, we conducted several robustness and falsification tests. First, we included additional controls such as the number of industrial firms to account for industrial development, import and export duties, and the number of treaty ports to account for trade effects, civil examination quotas to account for human capital foundations, and the number of telegraph and railway stations to account for communication infrastructure, as well as wars and natural disasters. The results remained robust. Second, we constructed placebo treatment variables and found that alternative interpretations of anti-tax unrest—including tax levels, xenophobia and nationalism, and general social disorder—were not driving banking development.

In the last empirical tests, we shed light on the dissemination of trust from the government to banks by examining the distinct dynamics in the development of official and private banks. Historical records suggest that government bonds were mainly underwritten by official banks initially. During this early stage, the rise of official banks was a by-product of public state building efforts. As these official banks matured and demonstrated their reliability and effectiveness, public trust extended to similar institutions established by the private sector. Our empirical analyses show that while the influence of anti-tax unrest on official banks was pronounced immediately after 1914, its impact on private banks became salient only after 1920. This implies a time-lagged spillover effect from official to private banks.

Finally, we present various anecdotes that support the broader applicability of our findings, suggesting that our main conclusion can be generalized to other countries. In nations such as Great Britain, the United States, and Japan, the establishment of the first modern banks often occurred under governmental auspices, particularly during times of financial shortfall driven by revolutions or wars. It was pervasive for governments and banks to appeal to patriotism while raising money from the populace.

In conclusion, this study highlights the crucial role of patriotism as a source of trust in government, which complements trust in the establishment and expansion of modern financial institutions. It provides new perspectives on the dynamic interaction among civilians, government, and banking development.

References

Besley, Timothy. 2020. “State Capacity, Reciprocity, and the Social Contract.” Econometrica 88 (4): 1307–35. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA16863.

Depetris-Chauvin, Emilio, Ruben Durante, and Filipe Campante. 2020. “Building Nations through Shared Experiences: Evidence from African Football.” American Economic Review 110 (5): 1572–1602. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180805.

Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales. 2004. “The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development.” American Economic Review 94 (3): 526–56. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041464498.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1762. The Social Contract. Paris.

Sun, Yuchen, Wanda Wang, and Yuchen Xu. 2024. “Bonds of Love: Patriotism and the Rise of Modern Banks.” UNSW Business School Research Paper. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4720595.

Wu, C. 1935. Zhongguo de Yinhang (Banks in China). Shanghai: Shangwu Yinshuguan.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email