How Does Salient Academic Rank Affect Student Performance? Insights from a Chinese Middle School Study

A current debate in education policy revolves around the impact of academic ranking systems on student motivation and mental health. As educators and policymakers grapple with how to foster a competitive yet supportive learning environment, the question of how academic performance is perceived by students and parents remains crucial. Have you ever wondered how your academic performance would be affected when your academic rank becomes salient to you and your parents? A fascinating study conducted in Chinese middle schools explores this question, revealing interesting insights into the effects and mechanisms of achievement rank when it is made salient to students and their parents.

Recent studies in the Netherlands, England, and the US show that students who rank higher in the classroom end up with improved educational outcomes later in life (Denning, Murphy, and Weinhardt 2023; Elsner and Isphording 2017; Elsner, Isphording, and Zölitz 2021; Murphy and Weinhardt 2020). However, most studies imply or assume that students are aware of their rankings. This raises a pertinent question: if students are unaware of their rankings, how can they respond to them? To address this important question, we leverage the context of Chinese middle schools in our recent paper (Megalokonomou and Zhang 2024), in which achievement ranks are clearly communicated to both students and parents.

Salience of rank

In recent years, several papers have examined rank effects. However, salience is a major issue for rank literature. Most studies assume that students have some understanding of their achievement rank, although they are rarely aware of this information (Goulas and Megalokonomou 2021, Devereux and Delaney 2022). However, in Chinese middle schools, it is common for students to be informed about their relative standing in the class due to its competitive nature. Students gauge their class ranks usually from their direct communication with their subject teachers, or from interactions among their classmates. Also, parents are often informed about their child’s class rank during regular parent-teacher meetings/conferences after midterm or final semester exams, or during home visitations by the teacher.

To study this important question, we utilized the China Education Panel Survey (CEPS) dataset from 2013 to 2015. This dataset offers a representative sample of seventh-grade middle school students, encompassing detailed demographic information about the students and their parents, baseline test scores, and insights into the beliefs and behaviors of students, parents, and teachers. The CEPS dataset also includes follow-up test scores for the same students in eighth grade, allowing us to connect their baseline performance with subsequent achievements.

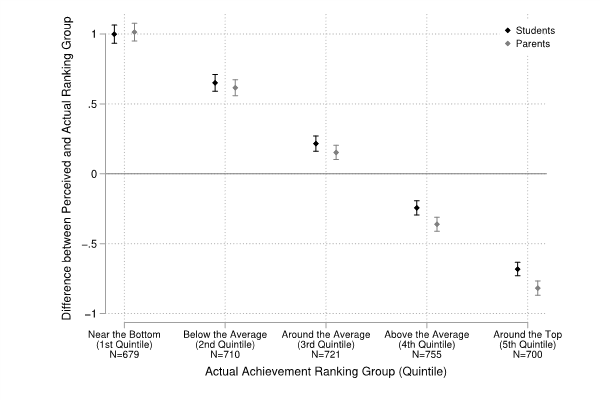

To address the concern about salience, we use this rich data and find that there is a strong correlation between perceived and actual rankings: 0.727 for students and 0.711 for parents. Figure 1 shows that the difference between perceptions of rank and students’ objective ranking group by students and parents. Achievement ranks are grouped into five quintiles, so that achievement ranks and perception of ranks are translated into the same scale from 1 (near the bottom) to 5 (near the top) for comparison purposes. The horizontal line indicates when the perceived equals the actual ranking group. Figure 1 suggests that students (and parents) tend to overestimate their achievement rank when they rank below the average and underestimate their ranks when they rank above the average. However, the overall extent of underestimation/overestimation is relatively modest, i.e., less than 1 ranking group (9 rank positions). The bottom line is that we find a strong positive correlation between objective and perceived achievement ranks, as assessed by both students and parents, which aligns with our expectations in this institutional setting.

Figure 1: Differences between perceptions of rank and rank by students and parents

Method and findings

We leverage the random assignment of students and teachers to classrooms in the sampled middle schools in China to study whether students with similar baseline test scores who find themselves obtaining different achievement ranks obtain different outcomes. Our main outcome is test scores in eighth grade. Students with the same baseline test scores end up obtaining different achievement ranks due to varying test score peers’ distributions in their randomly assigned classes.

Our findings indicate that being assigned a higher rank significantly improves students’ subsequent academic performance. For instance, a 1-standard-deviation increase in achievement rank boosts a student’s test score by 0.16 standard deviations—considerably higher than the increases observed in the UK (0.084 standard deviations) and the Netherlands (0.071 standard deviations). Our effects support the hypothesis that a more salient rank yields larger estimated rank effects. This probably explains why our estimated size is on the upper bound with regard to the existing literature.

This effect is particularly more pronounced among male students and those who are acutely aware of their ranking position within the class, highlighting the importance of rank salience in the competitive Chinese education system. This may be due to the fact that males on average have higher perception of rank and are more responsive to rank than females (Murphy and Weinhardt 2020, Bertoni and Nisticò 2023).

We then examine whether rank effects are nonlinear with respect to baseline performance. Figure 2 plots the rank effect estimates and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals, with the vertical line representing the median of the class (the reference group). The pattern shows a general increase in scholastic gains with achievement rank. In other words, rank effects demonstrate a nonlinear pattern: students who rank near the bottom of the class perform significantly worse relative to those ranking around the median of the class, while students who rank close to the top gain slightly more. Although scholastic gains are approximately monotonically increasing in rank, the effects exhibit a nonlinear trend with marginal diminishing returns.

Figure 2: Nonlinear rank effects (relative to the median)

Mechanisms at play

Most studies in the literature have focused on the channels of teachers’ investment, effort provision, social learning, and students’ learning confidence in response to ordinal rank (Murphy and Weinhardt 2020, Elsner and Isphording 2017, Goulas and Megalokonomou 2021, Dobrescu et al. 2021). Our study reveals that the positive impact of higher rank is not merely a product of enhanced self-perception or confidence in learning, but instead it comes from two main channels:

First, students with higher ranks exhibit greater self-awareness of their relative performance as well as increased confidence in mastering core subjects, and they dedicate more hours to independent study. This demonstrates the proactive role that awareness of academic standing can play. However, this channel has received attention in the literature before.

Second, our research highlights the critical influence of parental involvement, an area often overlooked in previous literature. In our setting, this is an interesting potential channel, because ranks are now salient to students’ parents; this feature is unique in this setting and has not been utilized before. Our survey data indicates that the academic gains associated with higher ranks are also shaped by parents' understanding of their child’s relative standing, the imposition of stricter study requirements, and elevated expectations regarding their child’s educational and career prospects.

Using a mediation analysis, we find that both channels—students’ internal motivations and self-awareness, as well as parental engagement—contribute equally to the effects of salient rank, accounting for a notable 46.80% increase in test scores. Interestingly, we found no evidence that rank impacts teachers’ investment or attention, emphasizing the unique interplay between students, parents, and their perceptions.

Our results offer valuable insights into how peer comparisons can influence student learning and future academic performance.

References

Bertoni, Marco, and Roberto Nisticò. 2023. “Ordinal Rank and the Structure of Ability Peer Effects.” Journal of Public Economics 217: 104797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2022.104797.

Denning, Jeffrey T., Richard Murphy, and Felix Weinhardt. 2023. “Class Rank and Long-Run Outcomes.” Review of Economics and Statistics 105 (6): 1426–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01125.

Devereux, Paul J., and Judith Delaney. 2022. “Rank Effects in Education.” VoxEU, 11 May. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/rank-effects-education.

Dobrescu, Loretti, Marco Faravelli, Rigissa Megalokonomou, and Alberto Motta. 2021. “Relative Performance Feedback in Education: Evidence from a Randomised Controlled Trial.” Economic Journal 131 (640), 3145–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueab043.

Elsner, Benjamin, and Ingo E. Isphording. 2017. “A Big Fish in a Small Pond: Ability Rank and Human Capital Investment.” Journal of Labor Economics 35 (3): 787–828. https://doi.org/10.1086/690714.

Elsner, Benjamin, Ingo E. Isphording, and Ulf Zölitz. 2021. “Achievement Rank Affects Performance and Major Choices in College.” Economic Journal 131 (640): 3182–3206. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueab034.

Goulas, Sofoklis, and Rigissa Megalokonomou. 2021. “Knowing Who You Actually Are: The Effect of Feedback on Short-and Longer-Term Outcomes.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 183: 589–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.01.013.

Megalokonomou, Rigissa, and Yi Zhang. 2024. “How Good Am I? Effects and Mechanisms Behind Salient Rank.” European Economic Review 170: 104870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2024.104870.

Murphy, Richard, and Felix Weinhardt. 2020. “Top of the Class: The Importance of Ordinal Rank.” Review of Economic Studies 87 (6): 2777–2826. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdaa020.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email