Input-Trade Liberalization, Female Skill Intensity, and Fertility in China

The interplay between trade liberalization and demographic behavior illuminates the challenges of reconciling career and family. This paper examines how gender-specific trade liberalization influences fertility, leveraging a Bartik-style shift-share instrumental variable strategy that incorporates female skill intensity into input tariff exposure. We find that input-trade liberalization significantly reduces fertility, particularly among highly educated women, private sector employees, and first-time mothers—groups experiencing the steepest career-family trade-offs. Mechanism analysis shows that enhanced labor market prospects raise the opportunity cost of childbearing, delaying or reducing family formation. These findings underscore the socioeconomic implications of trade policy for demographic trends.

Recent debates on declining fertility rates and aging populations have taken center stage in policy and academic circles worldwide. Beyond the usual focus on cultural shifts and family planning policies, a growing body of research points to the economic restructuring accompanying globalization as an important and often overlooked driver of demographic change (Autor et al. 2019, Keller and Utar 2022).

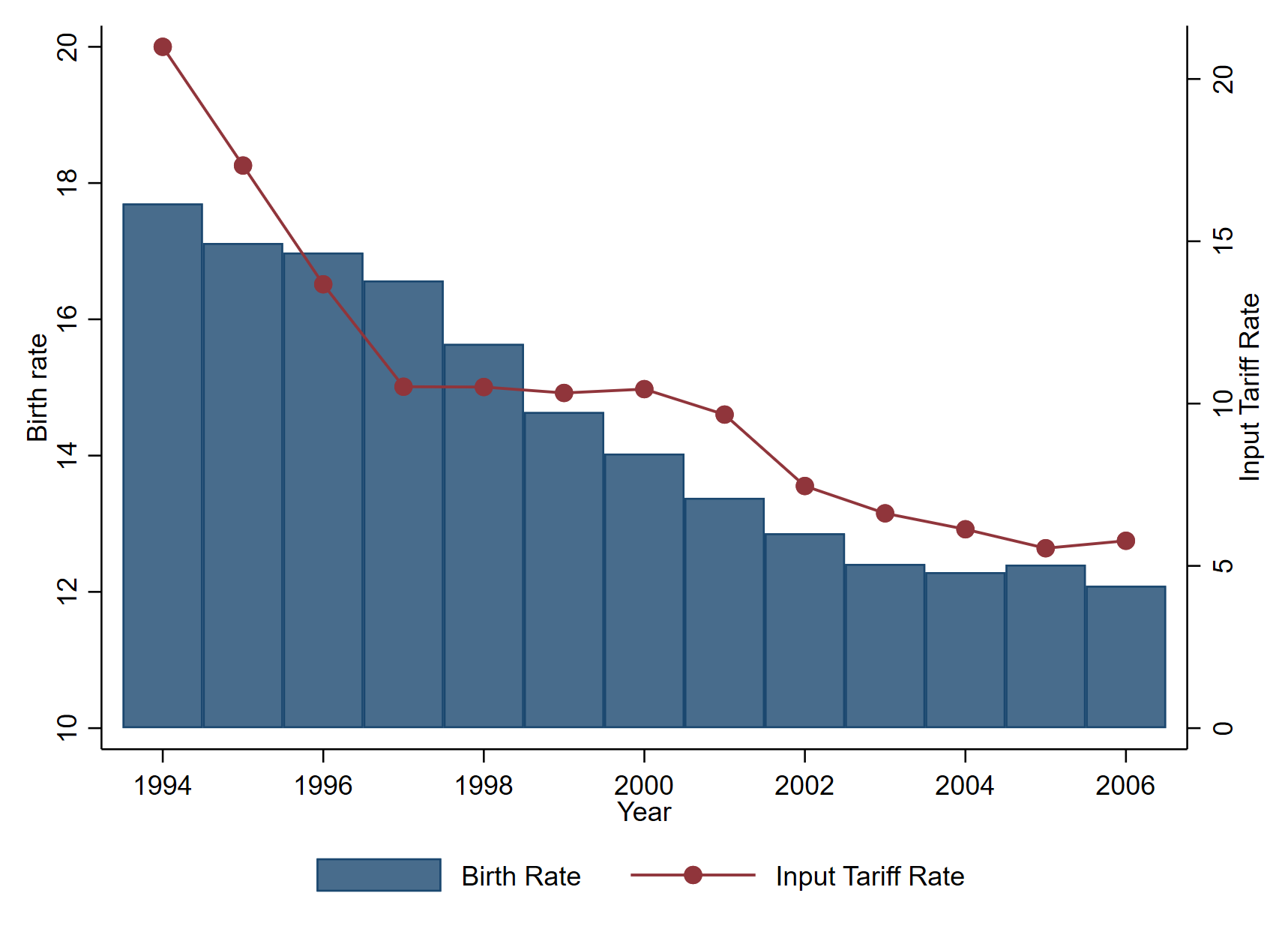

China’s economic transformation since the late 1970s has been marked by significant trade liberalization, particularly in the reduction of input tariffs. As China opened its markets, firms gained access to cheaper and higher-quality intermediate goods, which boosted productivity, especially in industries reliant on specialized labor, as highlighted by Yu (2015). This shift was particularly pronounced between 1992 and 2005, as shown in Figure 1. The impact on wages and productivity was particularly evident in sectors that demanded highly skilled labor, driving wage premiums for skilled workers (Han et al. 2012, Chen et al. 2017, Kondo et al. 2024).

While trade liberalization has been shown to have gendered effects on the labor market, especially in terms of wages and employment, the implications for women’s fertility choices remain understudied (Juhn et al. 2013, 2014; Wang et al. 2024). Input-trade liberalization, unlike other forms of trade liberalization, directly influences firms’ production processes and their demand for specialized labor. If the industries affected by tariff reductions rely more on female skills, the demand for female labor increases, especially for highly educated women. Consequently, the intensity of female skills in the sectors impacted by trade liberalization becomes a critical factor in shaping gendered labor market outcomes.

As firms in female-skill-intensive sectors benefit from reduced female-skill-oriented input costs, they expand their demand for skilled female workers, driving wage premiums and improving career prospects. However, these economic changes also bring about a growing opportunity cost of childbearing for highly educated women, as career opportunities in these sectors become more lucrative. This shift is central to understanding the relationship between trade liberalization and fertility trends in China. By incorporating female skill intensity into regional tariff measures, this paper offers a novel approach to studying the gendered impacts of trade, shedding light on how shifts in the labor market may contribute to China’s declining fertility rates, particularly among highly educated women.

Figure 1: Trends in Fertility Rates and Input Tariffs

Theoretical Underpinnings: Linking Input-Trade Liberalization to Fertility

Becker’s (1960) quantity-quality trade-off model provides a foundational framework for understanding fertility decisions, illustrating how households balance the number of children with the level of investment per child. This framework remains highly relevant in explaining broad fertility patterns, particularly in contexts where resource constraints shape household choices. Goldin’s (2021, 2024) career-family trade-off framework offers a complementary perspective, highlighting how expanding career opportunities and rising wages influence fertility decisions. As wages increase and career prospects improve, the opportunity cost of childbearing rises, prompting women to delay or reduce fertility in favor of professional advancement. This effect is especially pronounced in industries benefiting from input-trade liberalization, where firm expansion drives demand for skilled female labor, further reinforcing career incentives. The key hypothesis emerges from this framework:

Hypothesis: Input-trade liberalization disproportionately reduces fertility among highly educated women, with female skill intensity mediating this effect.

Input-trade liberalization raises wages and career opportunities for highly educated workers, particularly in skill-intensive industries. As firms benefit from lower input costs, they expand, offering higher wages and better career trajectories for highly skilled employees. Highly educated women face a sharp rise in the opportunity cost of childbearing. The higher financial and professional rewards of remaining in the workforce intensify the trade-off between career and family, leading these women to postpone or reduce fertility.

The fertility effect of trade liberalization hinges on industry-specific female skill intensity. When tariff reductions target female-skill-intensive industries, demand for female labor surges, amplifying career incentives and raising childbearing costs. In contrast, trade shocks in male-skill-intensive industries do not generate the same pressures, resulting in negligible or ambiguous effects on female fertility. Female skill intensity thus determines the extent to which trade liberalization influences fertility choices.

Empirical Evidence: Measuring Female-Specific Trade Shocks and Their Effects

This paper addresses three key challenges in studying trade liberalization's impact on fertility. First, China’s one-child policy complicates analysis, but focusing on highly educated women—who prioritize childrearing quality over quantity, have lower fertility intentions, and are less constrained by family planning policy—ensures more accurate results. Second, input-trade liberalization’s gender-neutral nature makes it difficult to isolate its effects on women, so the study incorporates female skill intensity to better capture the gendered impacts of trade shocks. Finally, disentangling trade’s causal effects from confounding factors is challenging, but we use a Bartik-style shift-share instrumental variable strategy with panel data to isolate exogenous variations in trade exposure and ensure valid causal inference.

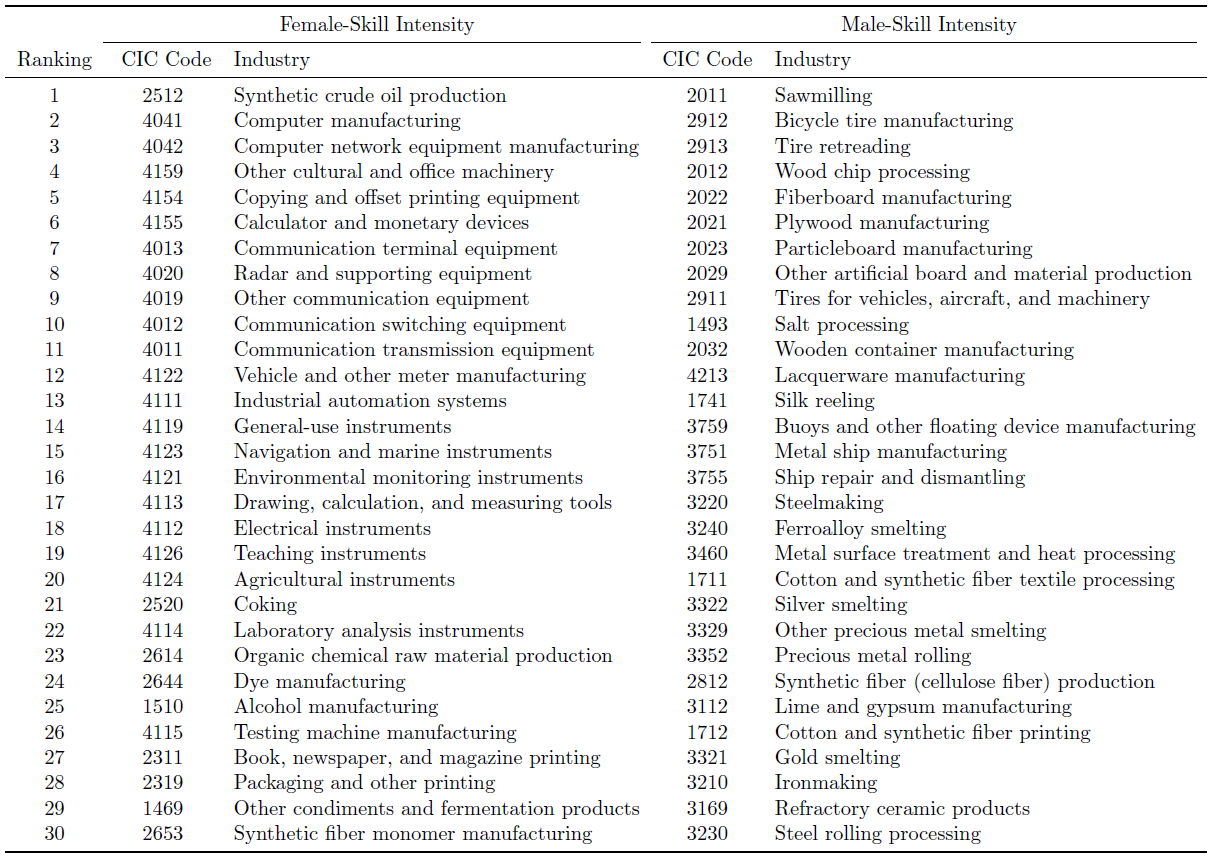

To measure female skill intensity, we adapt Li (2021) by using the O*NET database’s skill scores for occupations, focusing on skills like communication, negotiation, and coordination. These scores are weighted by employment shares and condensed using principal component analysis. The resulting scores are mapped to China’s four-digit industry classification to align with industrial and tariff data. As shown in Table 1, female skill intensity is highest in tech and service-oriented industries such as synthetic crude oil production, computer manufacturing, cultural, and office and teaching machinery, where communication, coordination, and negotiation are paramount, while male-skill intensity is concentrated in labor-intensive sectors like sawmilling, wood chip processing, and tire manufacturing.

Table 1: China’s Industries with the Top 30 Highest Female/Male Skill Intensity

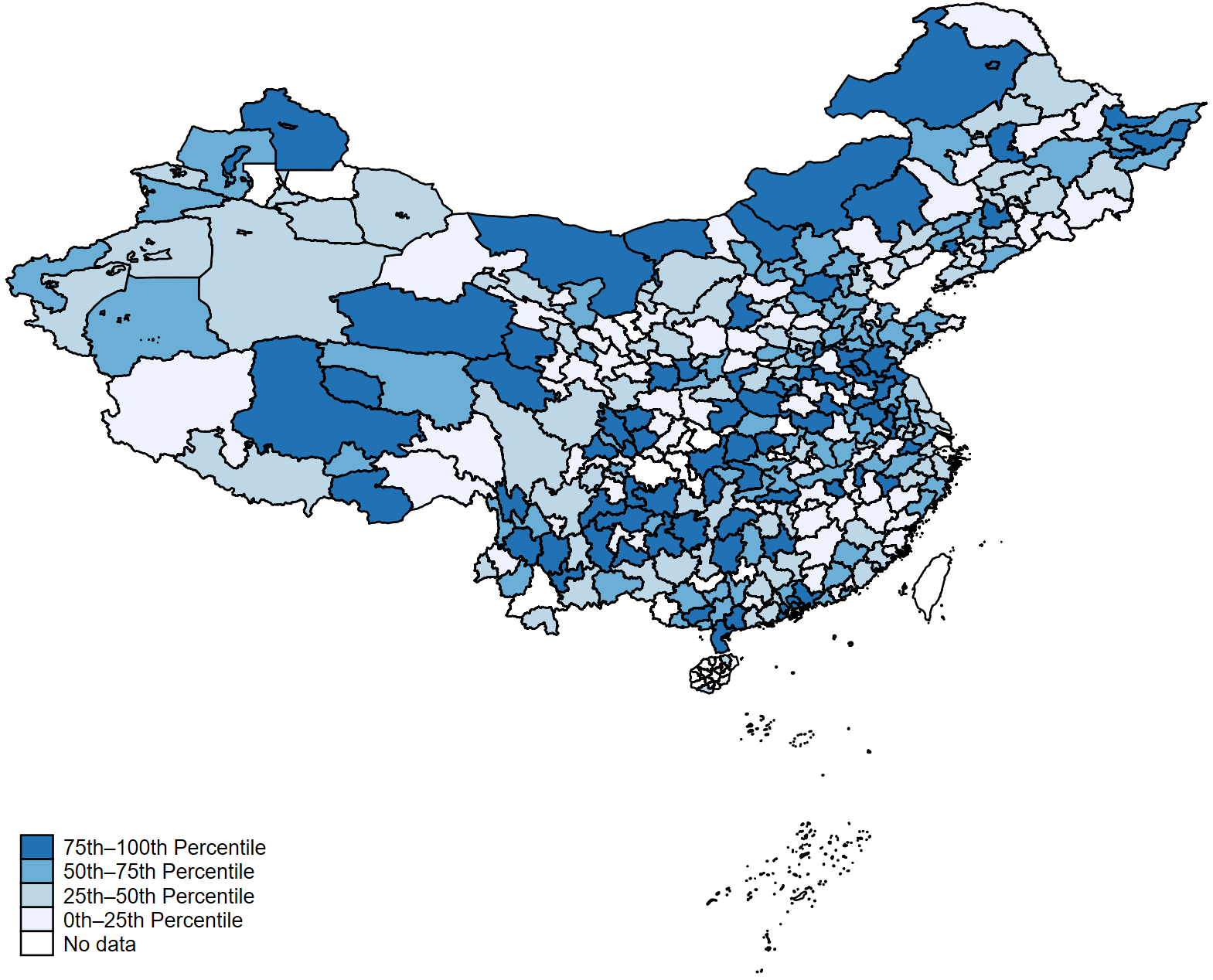

Once we establish each industry’s female skill intensity, we combine this measure with industry-specific input tariff data and local employment composition. In essence, for each city, we weight the input tariffs by both the pre-reform tradable employment shares and the corresponding female skill intensities. This process yields a city-level metric that reflects not only the magnitude of input tariffs, but also their likely impact on sectors reliant on female-associated skills. Figure 2 illustrates the reduction in female-skill-oriented input tariffs from 1992 to 2005, revealing significant differences compared to traditional input tariff reductions that do not account for female skill intensity.

Figure 2: Female-Skill-Oriented Input Tariff Reductions

After constructing the city-level exposure to female-skill-oriented input tariffs, we apply a Bartik-style shift-share instrumental variable strategy, leveraging regional and industry-level variation in trade shock intensity over the panel period, building on the frameworks of Bartik (1991), Kovak (2013), and Goldsmith-Pinkham et al. (2020). To summarize, our empirical analysis reveals several key findings that robustly support the above hypothesis:

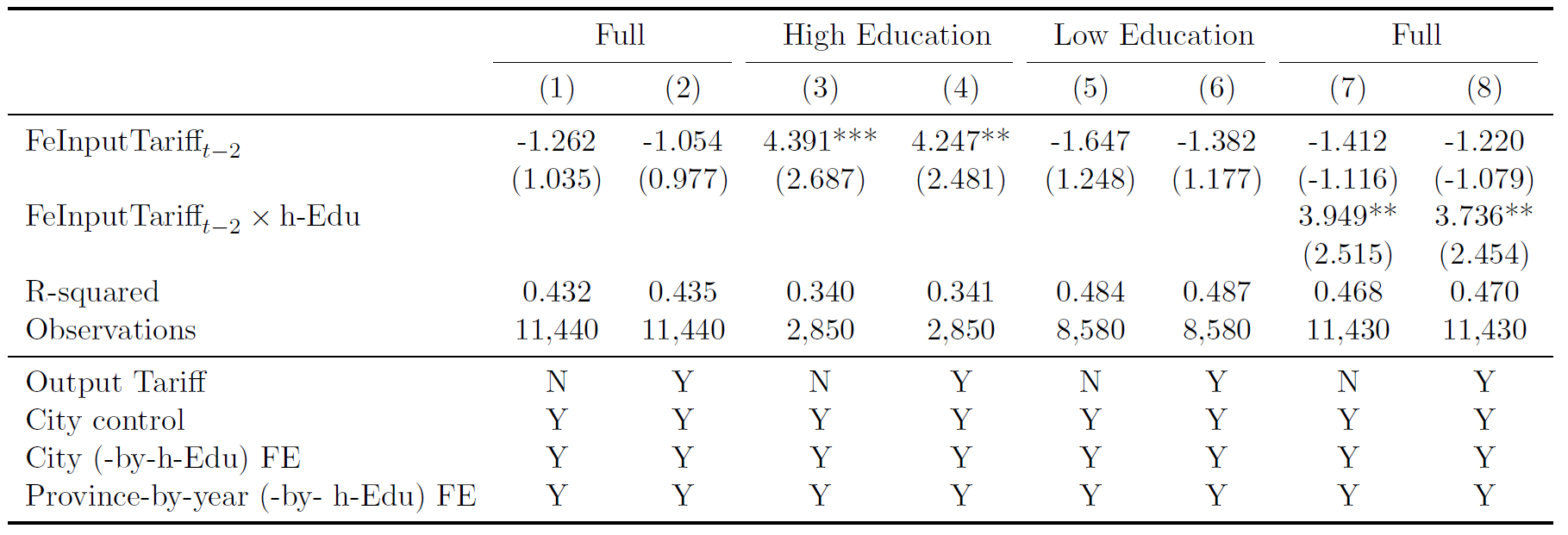

• As shown in Table 2, a one-percentage-point reduction in female-skill-oriented input tariffs is associated with roughly 4.25 fewer births per 1,000 women annually, particularly among the highly educated. These results remain robust across various model specifications, including alternative outcome variables, lag structures, and additional controls.

• Fertility effects are most pronounced among women aged 26–30, first-time mothers, and those employed in the private sector—groups that face acute career-family trade-offs.

• Placebo tests using control groups (such as agricultural workers and male employment) confirm that the observed fertility declines are driven by gender-specific labor market adjustments rather than broader economic trends.

• Further mechanism analyses indicate that enhanced employment opportunities and delays in early marriage are the primary channels through which these trade shocks influence fertility.

Table 2: Effects of Female-Skill-Oriented Input Tariff on Fertility

Conclusion

Trade liberalization is not merely an economic phenomenon, but a catalyst for profound demographic change. Linking gender-specific trade shocks to household decision making, our paper provides novel evidence of the impact of input-trade liberalization on fertility outcomes in China. Through the integration of data on tariffs, occupational skill composition, labor markets, and demographics, the study reveals that reductions in female-skill-oriented input tariffs enhance employment opportunities for highly educated women. As a result, the increased opportunities in female-intensive sectors raise the opportunity costs of childbearing, intensifying career-family trade-offs and leading to reduced fertility among highly educated women (Goldin 2021, 2024).

The empirical results demonstrate that trade liberalization’s fertility effects are concentrated among groups most affected by labor market changes, such as highly educated women and private sector employees. These findings are consistent across a range of robustness checks, including alternative outcome variables, lag structures, and additional controls. A set of placebo tests further validate the causal interpretation of the results. Potential economic mechanisms include enhanced female labor market opportunities and delays in early marriage, through which female-specific input-trade liberalization impacts fertility. In addition, women in their prime childbearing years and those at the margins of childbearing decisions exhibit the strongest responses, while individuals with strong family preferences or limited trade-induced labor market exposure are less affected.

This study contributes to the literature on trade and gender by offering new insights into the demographic effects of trade liberalization, with a particular focus on female-specific input tariffs. The findings emphasize the need for gender-specific considerations in trade policy design. Policies designed to mitigate career-family conflicts—such as expanding childcare access, offering flexible work arrangements, and providing targeted support for women in trade-exposed sectors—directly address the challenges identified in this study.

References

Autor, David, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson. 2019. “When Work Disappears: Manufacturing Decline and the Falling Marriage Market Value of Young Men.” American Economic Review: Insights 1 (2): 161–78. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20180010.

Bartik, Timothy J. 1991. Who Benefits from State and Local Economic Development Policies? W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Becker, Gary S. 1960. “An Economic Analysis of Fertility.” In Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chen, Bo, Miaojie Yu, and Zhihao Yu. 2017. “Measured Skill Premia and Input Trade Liberalization: Evidence from Chinese Firms.” Journal of International Economics 109: 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.08.005.

Goldin, Claudia. 2021. Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity. Princeton University Press.

Goldin, Claudia. 2024. “Babies and the Macroeconomy.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 33311. https://www.nber.org/papers/w33311.

Goldsmith-Pinkham, Paul, Isaac Sorkin, and Henry Swift. 2020. “Bartik Instruments: What, When, Why, and How.” American Economic Review 110 (8): 2586–2624. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181047.

Han, Jun, Runjuan Liu, and Junsen Zhang. 2012. “Globalization and Wage Inequality: Evidence from Urban China.” Journal of International Economics 87 (2): 288–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.12.006.

Juhn, Chinhui, Gergely Ujhelyi, and Carolina Villegas-Sanchez. 2013. “Trade Liberalization and Gender Inequality.” American Economic Review 103 (3): 269–73. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.269.

Juhn, Chinhui, Gergely Ujhelyi, and Carolina Villegas-Sanchez. 2014. “Men, Women, and Machines: How Trade Impacts Gender Inequality.” Journal of Development Economics 106: 179–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.09.009.

Keller, Wolfgang, and Hale Utar. 2022. “Globalization, Gender, and the Family.” Review of Economic Studies 89 (6): 3381–3409. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdac012.

Kondo, Illenin O., Yao Amber Li, and Wei Qian. 2024. “Trade Liberalization and Labor Monopsony: Evidence from Chinese Firms.” Journal of International Economics 152: 104006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2024.104006.

Kovak, Brian K. 2013. “Regional Effects of Trade Reform: What Is the Correct Measure of Liberalization?” American Economic Review 103 (5): 1960–76. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.5.1960.

Li, Jie. 2021. “Women Hold Up Half the Sky? Trade Specialization Patterns and Work-Related Gender Norms.” Journal of International Economics 128: 103407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2020.103407.

Wang, Feicheng, Krisztina Kis-Katos, and Minghai Zhou. 2024. “Import Competition and the Gender Employment Gap in China.” Journal of Human Resources 60 (1): 1830–64. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.1220-11399R3.

Yu, Miaojie. 2015. “Processing Trade, Tariff Reductions, and Firm Productivity: Evidence from Chinese Firms.” Economic Journal 125 (585): 943–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12127.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email