China Needs Tighter Macro-Prudential Regulations to Loosen Capital Controls

In a recent NBER working paper (authored by Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi, Andrea Ferrero, and Alessandro Rebucci) on the origins and the transmission of shocks to the international supply of credit, we provide indirect evidence that limits on the loan-to-value ratio (LTV) and the share of foreign exchange liabilities (FXL) could be effective in taming the global financial cycle.

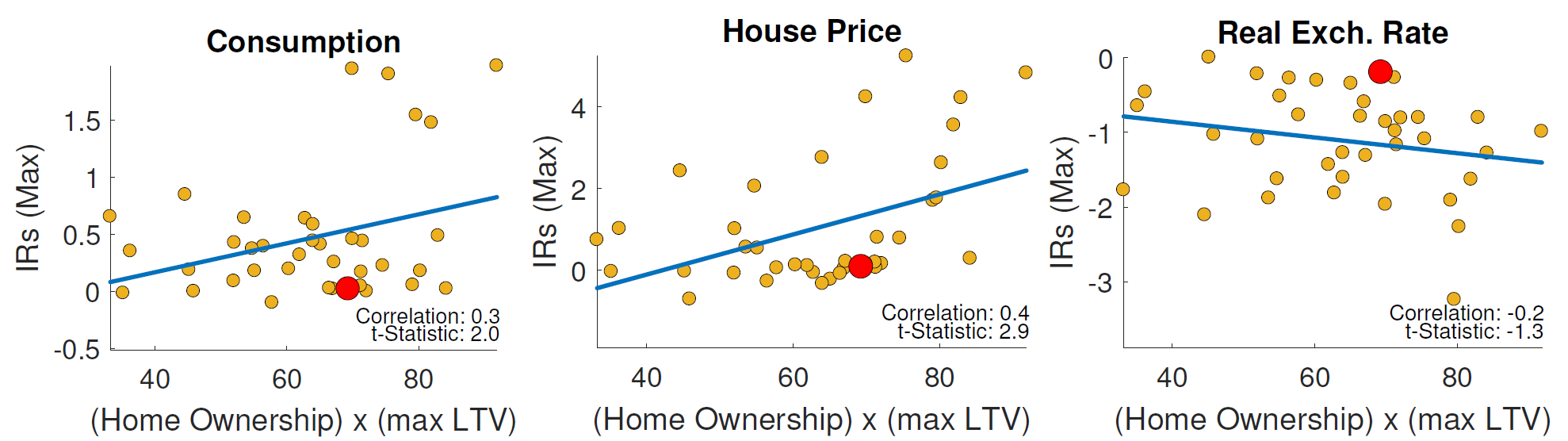

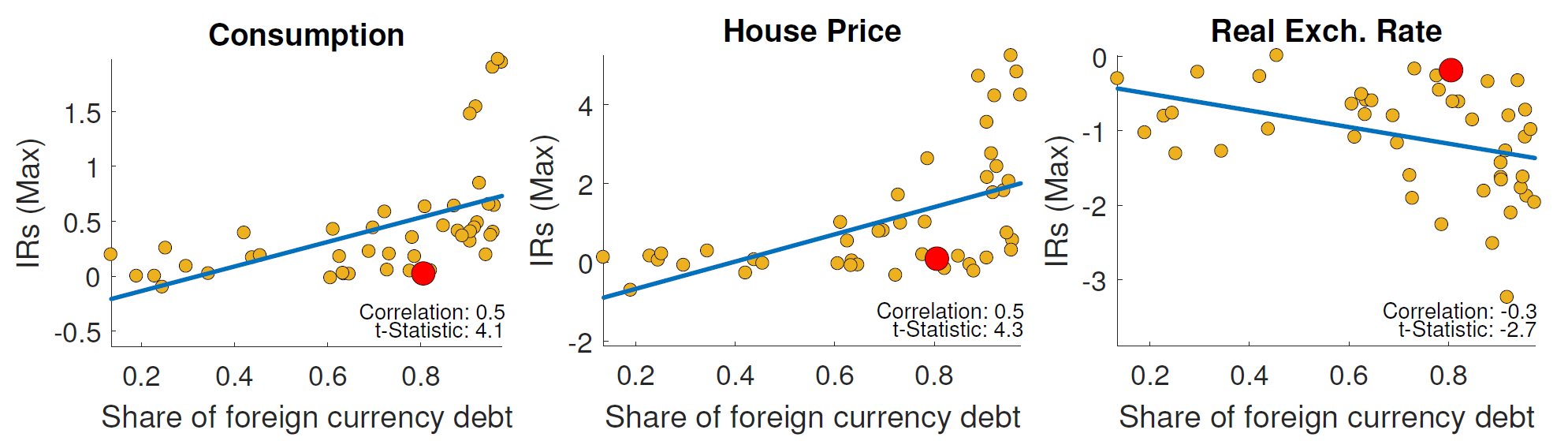

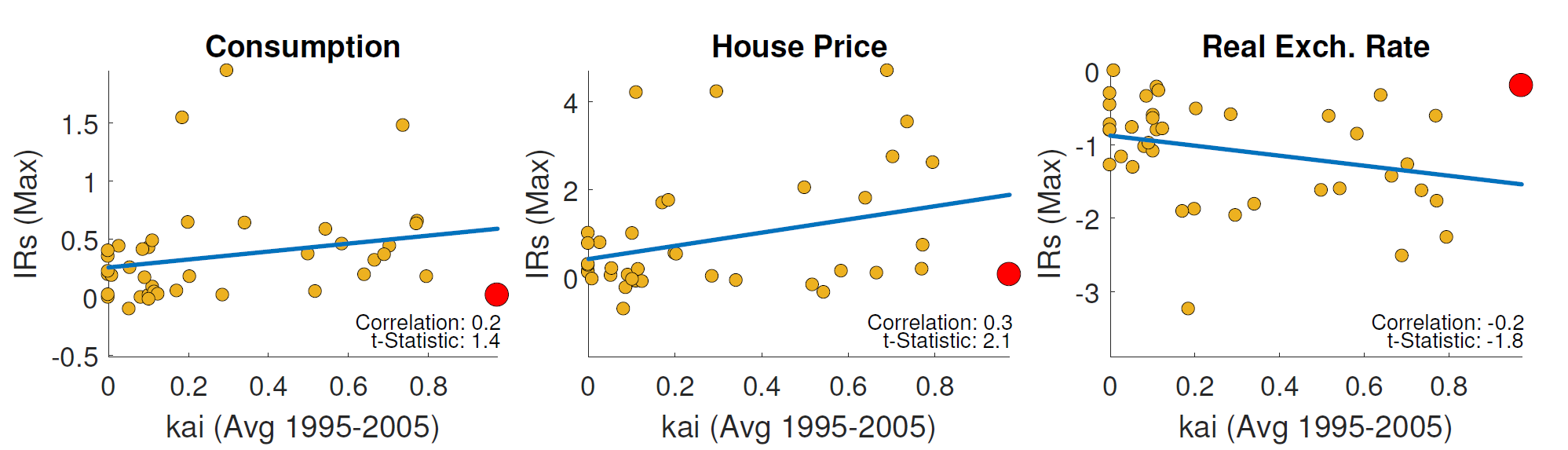

Figure 1 shows that countries with lower maximum LTV and FXL are significantly less sensitive to capital flow shocks. The figure plots the peak response of real private consumption, real house prices, and the real exchange rate vis-à-vis the US dollar to an international credit supply shock against the maximum LTV and the average FXL in a cross-section of 48 advanced and emerging economies (Panels A and B, respectively—correlation coefficient and t-statistics in parenthesis). In the scatter, the larger red dot is China.

Panel A. Peak impulse response and maximum loan to value ratio (LTV)

This shock is identified with a change in the leverage of US broker-dealers in a small open economy VAR that also includes BIS cross-border credit and the current account balance as a share of GDP. The identification of the external shock rests on the assumption that country-specific shocks are idiosyncratic and cannot affect the leverage of the US broker-dealer sector. To ensure that domestic shocks common across many small open economies do not affect leverage of US broker-dealers, in robustness checks we consider specifications that also include world GDP. The country sample excludes the United States.

In the paper, we also develop a model of collateralized borrowing with international financial intermediation to underpin the identification and the transmission of the shock in the VAR model. In the theoretical model, when leverage increases, possibly because of changes in the regulation of global banks, financial innovation, or monetary policy changes in the United States, global financial intermediaries have more capital to deploy and extend more and cheaper loans internationally. But the sensitivity of individual countries to the increased international supply of credit depends on domestic conditions.

If the economy is financially constrained before the shock, as it is plausible to assume for many households and firms in China, or if the shock is large enough to push credit demand against foreign lenders’ borrowing limits (even if the borrower was unconstrained before the shock), house price inflation magnifies the initial impact of the international credit supply expansion by inflating the value of housing collateral; the higher the maximum LTV and the average FXL, the greater the impact.

A lower LTV limit in the domestic economy implies that domestic households are less leveraged. Thus, if the credit constraint is binding, a given increase in house prices will have a smaller impact on the economy’s borrowing capacity and hence housing and non-housing consumption.

Exchange rate changes affect the transmission of the shock through three channels in this model, both when the economy is financially constrained and when it is not. But not all channels work in the same direction. An appreciation always strengthens the purchasing power of a given quantity of domestic output, but reduces the domestic currency value of a given amount of loans contracted in foreign currency. In addition, when the domestic borrowing constraint binds, an appreciation will inflate the foreign currency value of the collateral and hence boosts the borrowing capacity in foreign currency. The net effect of these three channels is a quantitative and empirical matter.

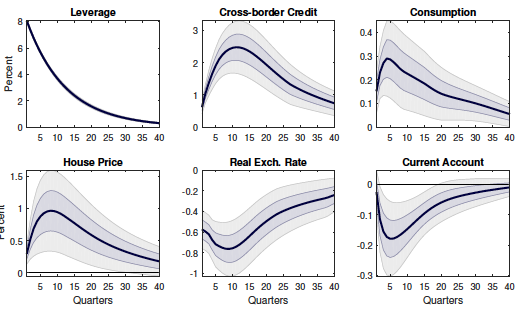

The VAR results shows that in a large cross-section of countries, the identified international credit supply shock pushes up cross-border credit and consumption (Figure 2). The typical economy (as represented by the average response) also displays current account deterioration, real exchange rate appreciation, and a house price boom. House price increases in particular are hump-shaped and consistent with real yields declining over time in line with the predicted drop in borrowing costs and yields on risky assets.

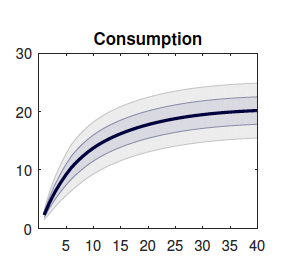

Importantly, the data also show that the identified shock explains a sizable portion of consumption variance in the typical small open economy, in the order of 15 percent of total variance (Figure 3). Both the impulse responses and the variance decomposition of consumption display significant heterogeneity across countries represented by the error bands around the mean estimate, which underpin the dispersion associated with LTV and FXL and reported in Figure 1.

What does this evidence mean for China? Figure 1 shows that China (depicted with a larger red dot in the scatter plots), thus far, has been relatively insulated from the global financial cycle, here represented by our international credit supply shock. The response of consumption, house prices, and the exchange rate are indeed close to zero. This is despite a relatively high share of foreign currency debt and maximum LTV limits.

But of course there are other country characteristics that affect an economy’s vulnerability to capital flow gyrations. Figure 4 shows that countries with a higher level of capital controls—China having one of the highest levels—are less sensitive to capital flow shocks.

This empirical evidence has important implications for China. Our results suggest that, if and when China opens its capital account as part of the renminbi internationalization process, it will likely experience increased volatility in response to international credit supply shocks. China, however, could tighten domestic macro-prudential regulation to manage its exposure to the global financial cycle. While LTV ratios and FXL shares are ultimately chosen by borrowers and lenders in the context of a given regulatory framework, our empirical evidence suggests that they are connected to consumption and asset price responses. As a result, by affecting the LTV and the FXL share, regulation might be able to influence market outcomes and thus stabilize the economy’s response to possibly inefficient capital flows shocks.

(Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi, Macro Financial Analysis Division of the Bank of England; Andrea Ferrero, Department of Economics at the University of Oxford; Alessandro Rebucci, the Johns Hopkins University Carey Business School.)

Benigno, Gianluca; Chen, Huigang; Otrok, Christopher; Rebucci, Alessandro; and Young, Eric R., 2016. “Optimal capital controls and real exchange rate policies: A pecuniary externality perspective,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Elsevier, 84(C), 147-165.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304393216301064

Cesa-Bianchi, Ambrogio; Ferrero, Andrea; and Rebucci, Alessando, 2017. “International Credit Supply Shocks,” NBER Working Papers 23841.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w23841

Cesa-Bianchi, Ambrogio and Rebucci, Alessandro, 2017) “Does easing monetary policy increase financial instability?” Journal of Financial Stability, 30, 111-125.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1572308917302620

Prasad, Eswar, 2016. “China’s efforts to expand the international use of the renminbi,” Report prepared for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Brookings Institution.

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/RMBReportFinal.pdf.

Rey, Helene, 2014. “Dilemma not trilemma: the global cycle and monetary policy

Independence,” Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

https://www.kansascityfed.org/bPmQP/publicat/sympos/2013/2013Rey.pdf.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email