Developing Credit Markets in Provinces Improves Innovation among Firms in the People’s Republic of China

Our recent research finds that provincial credit market development, through improving credit allocation, enhances firms’ product innovation incentives and outcomes in the People’s Republic of China. We further show that firms’ credit constraints and performance are two channels through which credit market development affects the innovative capacities of firms. We suggest that in order to further promote firms’ innovations, China should encourage financial institutions to actively screen those firms who have good performance but face credit constraints.

Innovation, as the engine of a firm’s development, has been considered a major driving force of economic growth (Solow 1957). With increasing globalization, competition, and labor costs, China considers innovation a pivotal development for the economy. Firms’ innovation requires financial support. Since most Chinese firms still heavily rely on credits from financial institutions for operation and investment, understanding how the credit market affects firms’ innovation is quite interesting and important.

In academics, researchers haven’t reached a consensus on how credit market development affects firm innovation. One part of the literature argues that creditors may promote innovation by identifying those entrepreneurs with the best chances of successfully initiating new goods and production processes and monitoring them to generate more innovation outputs (King and Levine 1993, Morales 2003, Levine 2005). Another part of the literature argues that credit market development discourages innovation. First, banks are conservative and dislike risky innovative projects (Weinstein and Yafeh 1998, Morck and Nakamura 1999). Second, banks do not favor firms with substantial research and development investments that generate intangible assets.

In a recent paper (Shang, Song and Wu, 2017), we find that in China, provincial credit market development using improving credit allocation stimulates firm’s product innovation incentives and promotes their product innovation outputs. Firms’ credit constraints and performance are two channels through which credit market development affects the innovative capacities of firms.

Provincial Credit Market Development in China

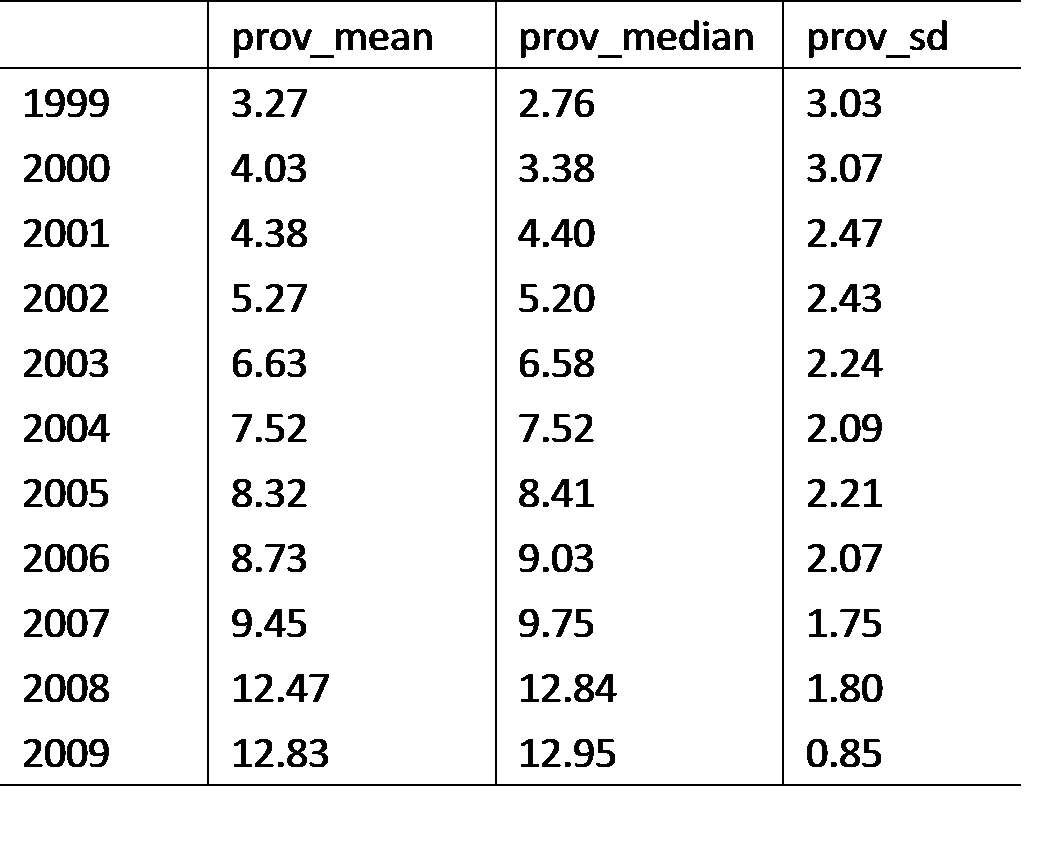

Compared to many other countries with developed financial systems, such as the United States and United Kingdom, the Chinese financial system is still underdeveloped. There is a long history that Chinese banks and other financial institutions prefer to lend to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) rather than non-SOEs, even though non-SOEs are in general more productive. Banks discriminate against non-SOEs due to their lack of credit history and smaller likelihood of being granted government bail-outs (Guariglia and Poncet 2008, Brandt and Li 2003). However, after several years of reform — including abolishing loan size restrictions, increasing competition among financial institutions, government encouragement of financial institutions to put effort into investigating the performance of SMEs, and government recognition of the importance of private firms — the proportion of credit allocated to non-SOEs increased over time. In Table 1, we provide summary statistics for the index of the share credit allocated to non-SOEs for 31 provinces [provided by Fan, Wang, and Zhu (2011) and sponsored by the National Economic Research Institute (NERI) and the PRC Reform Foundation]. We find that the average of the index in 2006 and 2009 are 2.67 and 3.93 times than in 1999, respectively. Additionally, credit allocation varies amongst provinces.

King and Levine (1993) argue that a financial system that allocates more financial resources to the private sector is more efficient and effective than one that allocates financial resources only to SOEs or publicly-listed enterprises. In the former, financial intermediaries are more active in screening and monitoring firms as well as managing risks. In the current market, the average credit allocated to non-SOEs in a province has increased over time, indicating that the provincial credit market is improving. However, the speed of improvement varies across different provinces.

Chinese Firms’ Innovation

We measure the product innovation incentive and outcomes using two measures constructed from the value of new products. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS), new products “refer to brand new products produced with new technology and new design, or products that represent noticeable improvement in terms of structure, material, or production process for improving significantly the character or function of the older versions. They include new products certified by relevant government agencies within the period of certification, as well as new products designed and produced by enterprises within a year without certification by government agencies. This indicator reflects the direct contribution of science and technology (S&T) output to economic growth (See Note 1).” Griliches (1990) argues that the number of patents is not a direct measure of innovative output because not all innovations are patented. Ayyagari, Demirguc-Kunt, and Maksimovic (2011) and the definition of innovation by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development show that product innovation reaches far beyond research and development and patenting, especially for emerging economies. As suggested by Zhang (2015), patented inventions are intermediate output and new product is final innovative output.

From the 891,462 observations provided by NBS — based on its annual surveys of industrial firms with sales of more than CNY 5 million in each province from 2000 to 2007, we find that in general, Chinese firms are not active in producing new products (See Note 2). Only 14.35 percent of the firms in this sample produced new products during the study period. Among the firms producing new products, they only spend approximately 40 percent of their time on new product development.

The Relation between Provincial Credit Market Development and Firms’ Innovation

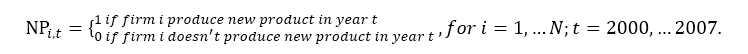

We use the pooled logit method and the tobit method to estimate provincial credit market development and firms’ product innovation incentives and output. The firms’ product innovation incentive is measured by a dummy variable NP, where

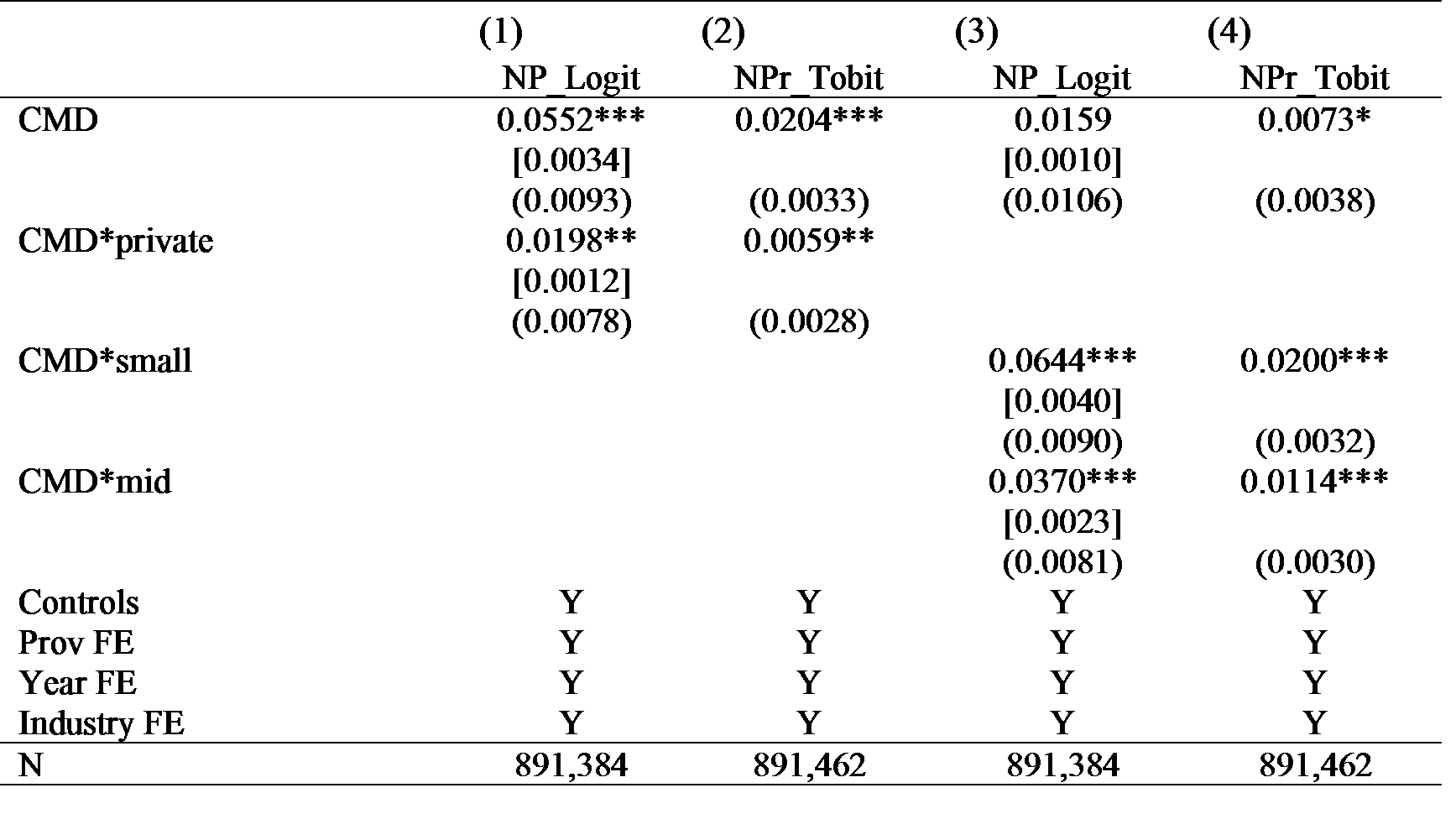

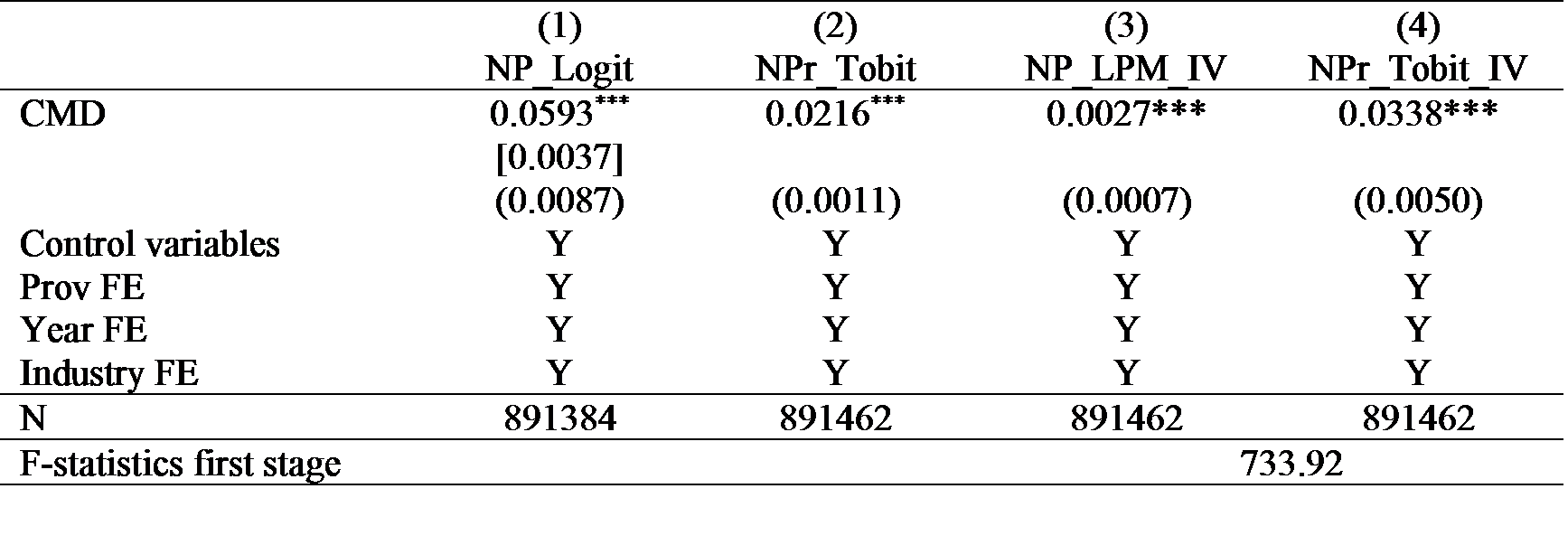

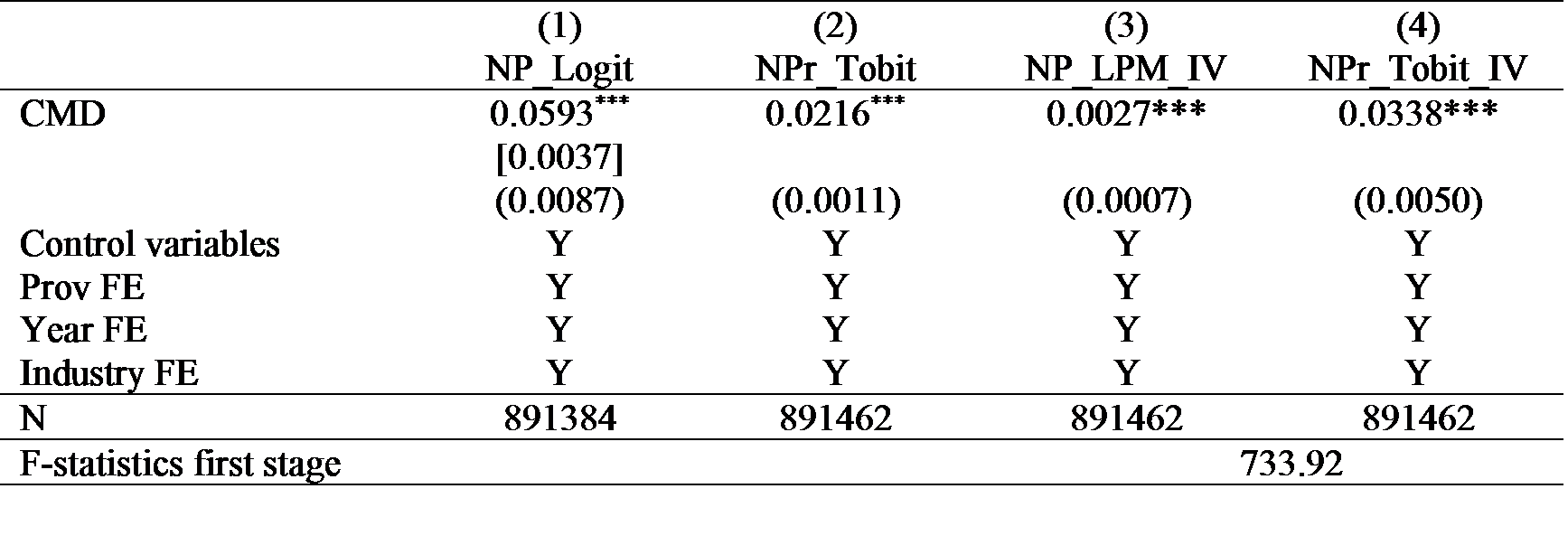

The results in Table 2 demonstrate that provincial credit market development, through improvement of credit allocation, enhances both the probability that firms will produce new products as well as increase the number of new products. When the index of the share of credit allocated to non-SOEs in a province increases by one point, around 471 (891,384/7 ×0.0037) firms engage in producing new products in one year and a firm is predicted to produce CNY1,441 (66,739.79×2.16%) more new products in one year on average.

One of the important problems in financial market development and innovation literature is the endogeneity problem caused by omitted variables and the reverse causality of finance and innovation. Following the most recent research (i.e., Ayyagari, Demirguc-Kunt, and Maksimovic 2011; Amore, Schneider, and Zaldokas 2013; etc.), we minimize the omitted variable problem by using firm-level innovation data. Firm-level analysis allows us to control for many unobserved variables such as firm-, industry-, and province-level variables that might affect both credit market development and firm innovation. We then lag the credit market development for one period to minimize the reverse causality problem.

In order to make our results more trustworthy, we apply the instrumental variable (IV) method to further deal with the endogeneity problem. Similar to Chong, Lu, and Ongena (2013), we construct an IV by using the average of the credit market development in neighboring provinces as the IV. First, the innovative capacities of firms in one province might not affect the credit market development in other provinces. Second, the credit market development of other provinces is not likely to affect the local firms’ innovative capacities since the Chinese credit market is region-specific (Qian and Yeung 2014). Bank branches are discouraged from lending to firms in other regions in order to minimize overlapping competition. Third, the first-stage F-test shows that our instrument is valid. Since the logit methods cannot accommodate the IV method, we use a linear probability model to estimate how credit market development affects firms’ product innovation incentives. The first-stage F-statistics show that the IV variable is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. The coefficients on the third and fourth columns of Table 2 are all statistically significant at the 1 percent level. This finding further reinforces the idea that credit market development, by improving credit allocation, promotes firms’ product innovation.

* significant at the 10 percent level, ** significant at the 5percent level, and *** significant at the 1 percent level.

Credit Constrained Firms

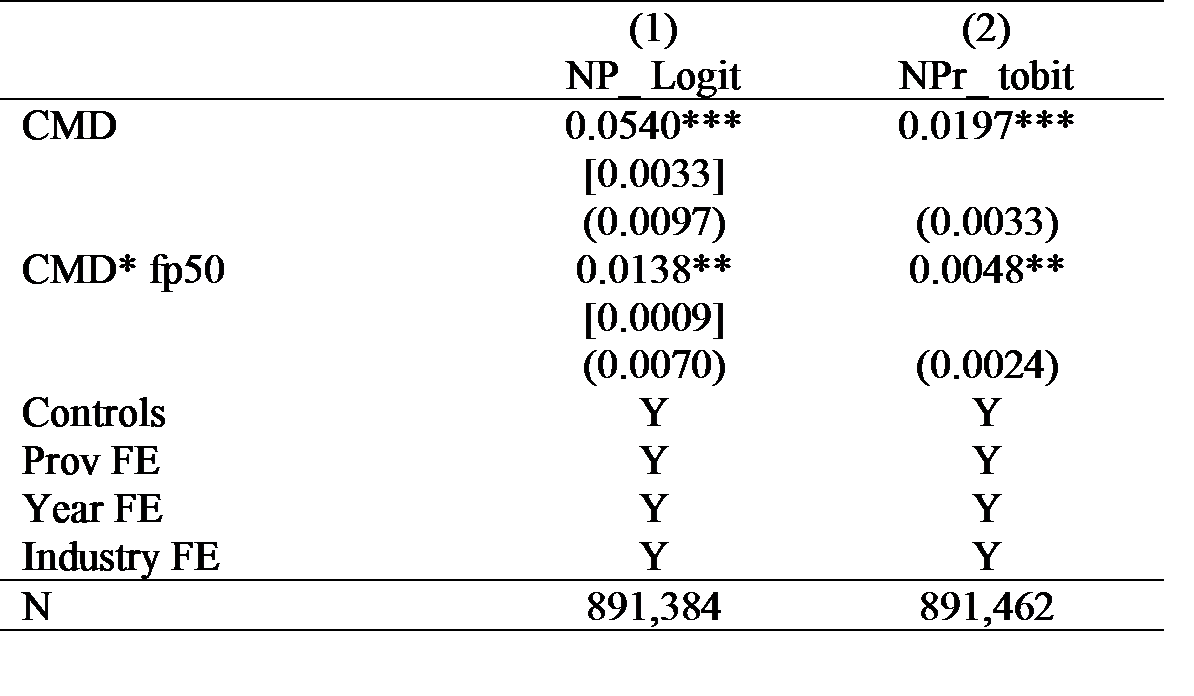

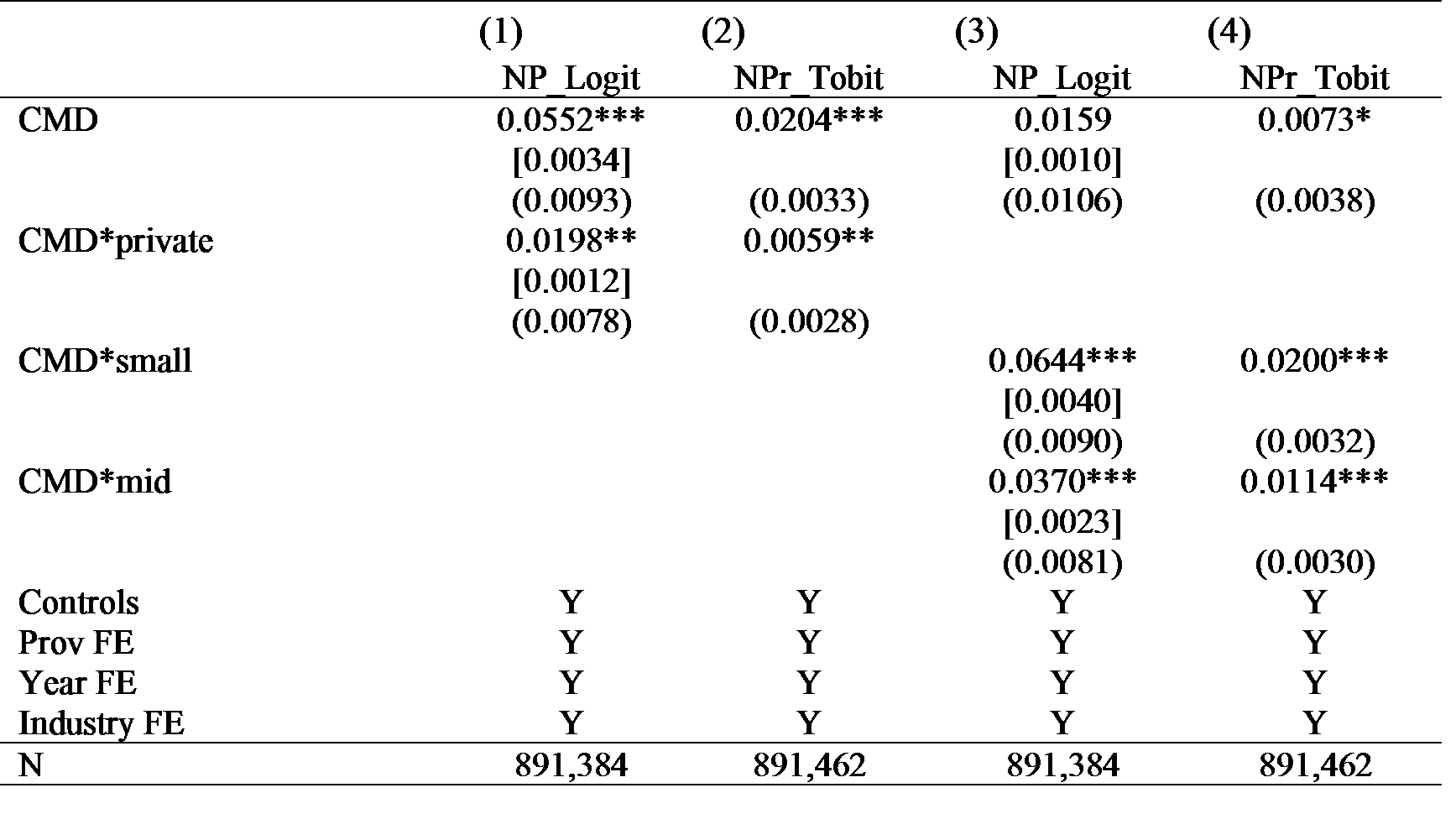

SMEs and privately-owned firms are more credit constrained than other firms. We find that the development of a provincial credit market affects SMEs and private firms more than other types of firms (Table 3). Compared to other types of firms, a one point increase of the index of the share of credit allocated to non-SOEs in a province induces around 153 (891,384/7 ×0.0012) more private firms versus other types of firms and 802 (891,384/7 ×0.0063) more SMEs versus large firms to produce new products. Additionally, a private firm is predicted to produce CNY 394 more in new products in one year on average than other types of firms, while a SME is predicted to produce CNY 2,096 more when compared to large firms. This finding indicates that the provincial credit market development, through improving credit allocation, affects Chinese firms’ innovation incentives and outcomes through alleviating firms’ credit constraints.

Note: This is part of Tables 4 and 5 in Shang, Song, and Wu (2017). The first two columns provide results for firms’ innovation incentives and firms’ innovation outcomes by comparing private firms with other firms. The last two columns provide results for firms’ innovation incentives and firms’ innovation outcomes by comparing SMEs with large firms. Coefficients in Columns (1) and (3) are estimated by the logit method. Coefficients in Columns (2) and (4) are estimated by the tobit method. All independent variables are lagged by one period. The standard errors are clustered by province and industry. CMD is the credit market development index. Private is a dummy of private firms. CMD*private denotes the interaction of private firms and CMD. Small is a dummy of small-sized firms. Middle is a dummy of middle-sized firms. CMD*small denotes the interaction of small firms and CMD. CMD*mid denotes the interaction of mid-size firms and CMD. For simplicity, we do not report the estimation results for other control variables. Standard errors are in parentheses. Marginal effects are in square brackets.

* significant at the 10 percent level, ** significant at the 5percent level, and *** significant at the 1 percent level.

Firms with Better Financial Performances

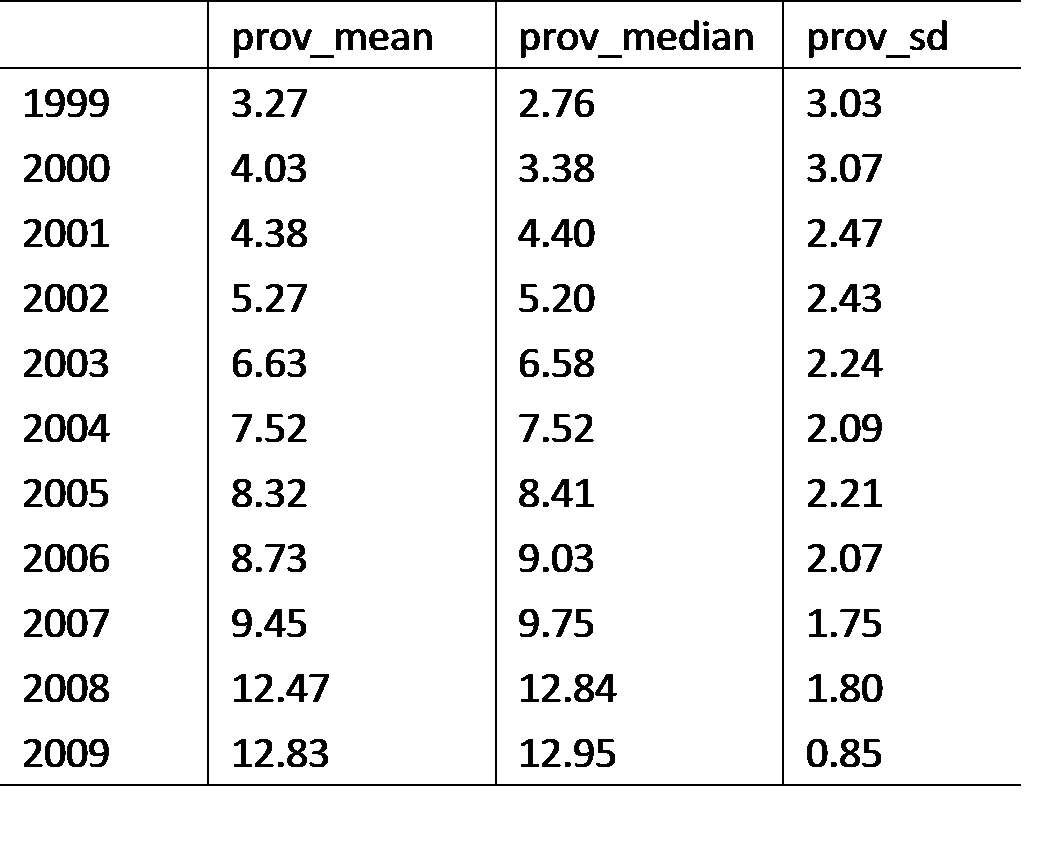

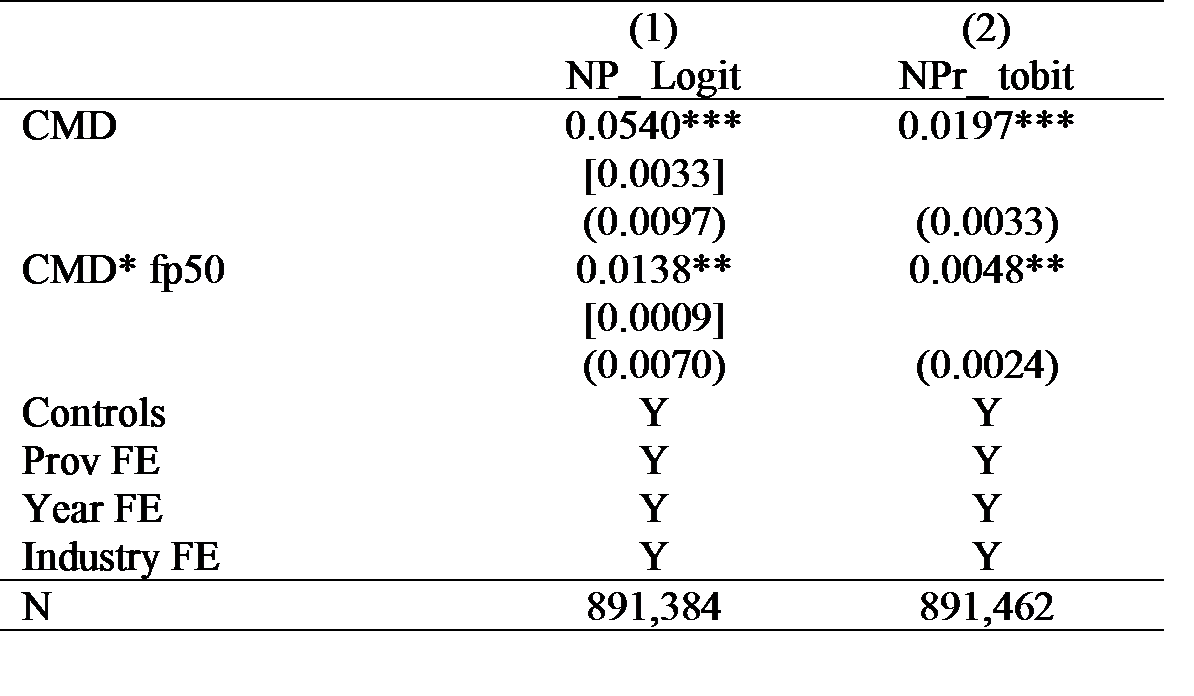

As financial institutions become more active in investigating firms and projects instead of just allocating credit to SOEs following government directives, they will be more likely to lend to firms with better performance. We use return on assets (ROA) as a proxy for firm performance. We find that, compared with low-performance firms, the effect of provincial credit market development on high-performance firms’ product innovation incentives and outcomes is 0.09 percent higher and 0.48 percent higher, respectively.

Note: This is part of Table 6 in Shang, Song, and Wu (2017). The first column provides results for firms’ innovation incentives. Coefficients are estimated by the logit method. The second column provides results for firms’ innovation outcomes. Coefficients are estimated by the tobit method. All independent variables are lagged by one period. The standard errors are clustered by province and industry. CMD is the credit market development index. The variable fp50 is a dummy of profitable firms in the first 50th percentile of all firms in the same province and industry. CMD*fp50 denotes the interaction of fp50 and CMD. For simplicity, we do not report the estimation results for other control variables. Standard errors are in parentheses. The marginal effects are in square brackets.

* significant at the 10 percent level, ** significant at the 5percent level, and *** significant at the 1 percent level.

Our results are robust to different samples, different estimation methods, and alternative measures of credit market development.

Conclusion

In this article, we examine the effects of provincial credit market development on firms’ product innovation incentives and outcomes in China. We find that development of the provincial credit market by improving credit allocation increases the number of firms engaging in innovative activities and also promotes firms’ innovation. The credit constrained firms and firms with better performance are more affected by the development of a provincial credit market.

Note 1: Please see Explanatory Notes on Main Statistical Indicators in Section 20 from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2008/indexeh.htm.

Note2: The available data is until 2007. Many researches use the data until 2007, including Brandt et al., 2017.

Amore, M. D., C. Schneider, and A. Žaldokas (2013), “Credit Supply and Corporate Innovation,” Journal of Financial Economics 109: 835–855. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X1300113X.

Ayyagari, M., A. Demirguc-Kunt, and V. Maksimovic (2011), “Firm Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Role of Finance, Governance, and Competition,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46: 1545–1580. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-financial-and-quantitative-analysis/article/firm-innovation-in-emerging-markets-the-role-of-finance-governance-and-competition/16657B8C16B18EA52916B20BD608E4A5.

Brandt, L., and H. B. Li (2003), “Bank Discrimination in Transition Economies: Ideology, Information, or Incentives?”, Journal of Comparative Economics 31: 387–413. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0147596703000805.

Chong, T. L., L. Lu, and S. Ongena (2013), “Does Banking Competition Alleviate or Worsen Credit Constraints Faced by Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises? Evidence from China,” Journal of Banking and Finance 37: 3412–3424. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378426613002240.

Fan, G., X. Wang, and H. P. Zhu (2011). NERI Index of Marketization of China’s Provinces. Beijing, China: Economics Science Press, Beijing (in Chinese). http://book.blyun.com/views/specific/3004/bookDetail.jsp?dxNumber=000008245131&d=964FE83CA63628B3676CDEA15A897FCB&fenlei=06020204.

Griliches, Z (1990), “Patent Statistics as Economic Indicator: A Survey,” Journal of Economic Literature 28: 1661–1707. http://www.edegan.com/pdfs/Griliches%20(1990)%20-%20Patent%20Statistics%20as%20Economic%20Indicators.pdf.

Guariglia, A., and S. Poncet (2008), “Could Financial Distortions Be No Impediment to Economic Growth after All? Evidence from China,” Journal of Comparative Economics 36: 633–657. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014759670700090X.

King, R. G., and R. Levine (1993), “Finance, Entrepreneurship and Growth: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Monetary Economics 32: 513-542. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/030439329390028E.

Levine, R (2005). “Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence.” In Handbook of Economic Growth. Edited by P. Aghion and S. Durlauf. Netherlands: Elsevier Science. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1574068405010129.

Morales, M. F. (2003), “Financial Intermediation in a Model of Growth through Creative Destruction,” Macroeconomic Dynamics 7: 363–393. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/macroeconomic-dynamics/article/financial-intermediation-in-a-model-of-growth-through-creative-destruction/2ED1FA0DFF819DD109D642525C692557.

Morck, R., and M. Nakamura (1999), “Banks and Corporate Control in Japan,” Journal of Finance 54: 319–340. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/0022-1082.00106/full.

Qian, M., and B. Y. Yeung (2014), “Bank Financing and Corporate Governance,” Journal of Corporate Finance 32: 258–270. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929119914001229.

Shang, H., Q. Y. Song, and Y. Wu (2017), “Credit Market Development and Firm Innovation: Evidence from the People’s Republic of China,” Journal of the Asian and Pacific Economy 22: 71-89. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13547860.2016.1261476 and https://www.adb.org/publications/credit-market-development-and-firm-innovation-evidence-prc.

Solow, R. M (1957), “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function,” Review of Economics and Statistics 39: 312–320. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1926047.

Weinstein, D. E., and Y. Yafeh (1998), “On the Costs of a Bank-centered Financial System: Evidence from the Changing Main Bank Relations in Japan,” Journal of Finance 53: 635–672. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/0022-1082.254893/full.

Innovation, as the engine of a firm’s development, has been considered a major driving force of economic growth (Solow 1957). With increasing globalization, competition, and labor costs, China considers innovation a pivotal development for the economy. Firms’ innovation requires financial support. Since most Chinese firms still heavily rely on credits from financial institutions for operation and investment, understanding how the credit market affects firms’ innovation is quite interesting and important.

In academics, researchers haven’t reached a consensus on how credit market development affects firm innovation. One part of the literature argues that creditors may promote innovation by identifying those entrepreneurs with the best chances of successfully initiating new goods and production processes and monitoring them to generate more innovation outputs (King and Levine 1993, Morales 2003, Levine 2005). Another part of the literature argues that credit market development discourages innovation. First, banks are conservative and dislike risky innovative projects (Weinstein and Yafeh 1998, Morck and Nakamura 1999). Second, banks do not favor firms with substantial research and development investments that generate intangible assets.

In a recent paper (Shang, Song and Wu, 2017), we find that in China, provincial credit market development using improving credit allocation stimulates firm’s product innovation incentives and promotes their product innovation outputs. Firms’ credit constraints and performance are two channels through which credit market development affects the innovative capacities of firms.

Provincial Credit Market Development in China

Compared to many other countries with developed financial systems, such as the United States and United Kingdom, the Chinese financial system is still underdeveloped. There is a long history that Chinese banks and other financial institutions prefer to lend to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) rather than non-SOEs, even though non-SOEs are in general more productive. Banks discriminate against non-SOEs due to their lack of credit history and smaller likelihood of being granted government bail-outs (Guariglia and Poncet 2008, Brandt and Li 2003). However, after several years of reform — including abolishing loan size restrictions, increasing competition among financial institutions, government encouragement of financial institutions to put effort into investigating the performance of SMEs, and government recognition of the importance of private firms — the proportion of credit allocated to non-SOEs increased over time. In Table 1, we provide summary statistics for the index of the share credit allocated to non-SOEs for 31 provinces [provided by Fan, Wang, and Zhu (2011) and sponsored by the National Economic Research Institute (NERI) and the PRC Reform Foundation]. We find that the average of the index in 2006 and 2009 are 2.67 and 3.93 times than in 1999, respectively. Additionally, credit allocation varies amongst provinces.

King and Levine (1993) argue that a financial system that allocates more financial resources to the private sector is more efficient and effective than one that allocates financial resources only to SOEs or publicly-listed enterprises. In the former, financial intermediaries are more active in screening and monitoring firms as well as managing risks. In the current market, the average credit allocated to non-SOEs in a province has increased over time, indicating that the provincial credit market is improving. However, the speed of improvement varies across different provinces.

Table 1: Summary Statistics of the Credit Market Development Index in 31 Provinces from 1999 to 2009

Chinese Firms’ Innovation

We measure the product innovation incentive and outcomes using two measures constructed from the value of new products. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS), new products “refer to brand new products produced with new technology and new design, or products that represent noticeable improvement in terms of structure, material, or production process for improving significantly the character or function of the older versions. They include new products certified by relevant government agencies within the period of certification, as well as new products designed and produced by enterprises within a year without certification by government agencies. This indicator reflects the direct contribution of science and technology (S&T) output to economic growth (See Note 1).” Griliches (1990) argues that the number of patents is not a direct measure of innovative output because not all innovations are patented. Ayyagari, Demirguc-Kunt, and Maksimovic (2011) and the definition of innovation by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development show that product innovation reaches far beyond research and development and patenting, especially for emerging economies. As suggested by Zhang (2015), patented inventions are intermediate output and new product is final innovative output.

From the 891,462 observations provided by NBS — based on its annual surveys of industrial firms with sales of more than CNY 5 million in each province from 2000 to 2007, we find that in general, Chinese firms are not active in producing new products (See Note 2). Only 14.35 percent of the firms in this sample produced new products during the study period. Among the firms producing new products, they only spend approximately 40 percent of their time on new product development.

The Relation between Provincial Credit Market Development and Firms’ Innovation

We use the pooled logit method and the tobit method to estimate provincial credit market development and firms’ product innovation incentives and output. The firms’ product innovation incentive is measured by a dummy variable NP, where

The results in Table 2 demonstrate that provincial credit market development, through improvement of credit allocation, enhances both the probability that firms will produce new products as well as increase the number of new products. When the index of the share of credit allocated to non-SOEs in a province increases by one point, around 471 (891,384/7 ×0.0037) firms engage in producing new products in one year and a firm is predicted to produce CNY1,441 (66,739.79×2.16%) more new products in one year on average.

One of the important problems in financial market development and innovation literature is the endogeneity problem caused by omitted variables and the reverse causality of finance and innovation. Following the most recent research (i.e., Ayyagari, Demirguc-Kunt, and Maksimovic 2011; Amore, Schneider, and Zaldokas 2013; etc.), we minimize the omitted variable problem by using firm-level innovation data. Firm-level analysis allows us to control for many unobserved variables such as firm-, industry-, and province-level variables that might affect both credit market development and firm innovation. We then lag the credit market development for one period to minimize the reverse causality problem.

In order to make our results more trustworthy, we apply the instrumental variable (IV) method to further deal with the endogeneity problem. Similar to Chong, Lu, and Ongena (2013), we construct an IV by using the average of the credit market development in neighboring provinces as the IV. First, the innovative capacities of firms in one province might not affect the credit market development in other provinces. Second, the credit market development of other provinces is not likely to affect the local firms’ innovative capacities since the Chinese credit market is region-specific (Qian and Yeung 2014). Bank branches are discouraged from lending to firms in other regions in order to minimize overlapping competition. Third, the first-stage F-test shows that our instrument is valid. Since the logit methods cannot accommodate the IV method, we use a linear probability model to estimate how credit market development affects firms’ product innovation incentives. The first-stage F-statistics show that the IV variable is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. The coefficients on the third and fourth columns of Table 2 are all statistically significant at the 1 percent level. This finding further reinforces the idea that credit market development, by improving credit allocation, promotes firms’ product innovation.

Table 2: Credit Market Development and Firm Innovation: Full Sample

Note: This is part of Tables 3 and 7 in Shang, Song, and Wu (2017). The first and third columns provide results for firms’ product innovation incentives. Coefficients from the first column are estimated by the logit method. Coefficients from the second column are estimated using the linear probability model. The second and fourth columns provide results for firms’ product innovation outcomes. Coefficients are estimated by the tobit method. The third and fourth columns use the instrumental variable method. All independent variables are lagged by one period. The standard errors are clustered by province and industry. CMD is the credit market development index. Standard errors are in parentheses. The marginal effect for CMD is in square brackets. For simplicity, we do not report the estimation results for other control variables.

* significant at the 10 percent level, ** significant at the 5percent level, and *** significant at the 1 percent level.

Credit Constrained Firms

SMEs and privately-owned firms are more credit constrained than other firms. We find that the development of a provincial credit market affects SMEs and private firms more than other types of firms (Table 3). Compared to other types of firms, a one point increase of the index of the share of credit allocated to non-SOEs in a province induces around 153 (891,384/7 ×0.0012) more private firms versus other types of firms and 802 (891,384/7 ×0.0063) more SMEs versus large firms to produce new products. Additionally, a private firm is predicted to produce CNY 394 more in new products in one year on average than other types of firms, while a SME is predicted to produce CNY 2,096 more when compared to large firms. This finding indicates that the provincial credit market development, through improving credit allocation, affects Chinese firms’ innovation incentives and outcomes through alleviating firms’ credit constraints.

Table 3: Credit Market Development and Firm Innovation: Credit Constrained Firms

* significant at the 10 percent level, ** significant at the 5percent level, and *** significant at the 1 percent level.

Firms with Better Financial Performances

As financial institutions become more active in investigating firms and projects instead of just allocating credit to SOEs following government directives, they will be more likely to lend to firms with better performance. We use return on assets (ROA) as a proxy for firm performance. We find that, compared with low-performance firms, the effect of provincial credit market development on high-performance firms’ product innovation incentives and outcomes is 0.09 percent higher and 0.48 percent higher, respectively.

Table 4: Credit Market Development and Firm Innovation: Better Performance versus Others

* significant at the 10 percent level, ** significant at the 5percent level, and *** significant at the 1 percent level.

Our results are robust to different samples, different estimation methods, and alternative measures of credit market development.

Conclusion

In this article, we examine the effects of provincial credit market development on firms’ product innovation incentives and outcomes in China. We find that development of the provincial credit market by improving credit allocation increases the number of firms engaging in innovative activities and also promotes firms’ innovation. The credit constrained firms and firms with better performance are more affected by the development of a provincial credit market.

Note 1: Please see Explanatory Notes on Main Statistical Indicators in Section 20 from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2008/indexeh.htm.

Note2: The available data is until 2007. Many researches use the data until 2007, including Brandt et al., 2017.

(Hua Shang, Research Institute of Economics and Management, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics; Quanyun Song, Finance School, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics; and Yu Wu, Survey and Research Center for China Household Finance, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.)

Amore, M. D., C. Schneider, and A. Žaldokas (2013), “Credit Supply and Corporate Innovation,” Journal of Financial Economics 109: 835–855. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X1300113X.

Ayyagari, M., A. Demirguc-Kunt, and V. Maksimovic (2011), “Firm Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Role of Finance, Governance, and Competition,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46: 1545–1580. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-financial-and-quantitative-analysis/article/firm-innovation-in-emerging-markets-the-role-of-finance-governance-and-competition/16657B8C16B18EA52916B20BD608E4A5.

Brandt, L., and H. B. Li (2003), “Bank Discrimination in Transition Economies: Ideology, Information, or Incentives?”, Journal of Comparative Economics 31: 387–413. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0147596703000805.

Chong, T. L., L. Lu, and S. Ongena (2013), “Does Banking Competition Alleviate or Worsen Credit Constraints Faced by Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises? Evidence from China,” Journal of Banking and Finance 37: 3412–3424. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378426613002240.

Fan, G., X. Wang, and H. P. Zhu (2011). NERI Index of Marketization of China’s Provinces. Beijing, China: Economics Science Press, Beijing (in Chinese). http://book.blyun.com/views/specific/3004/bookDetail.jsp?dxNumber=000008245131&d=964FE83CA63628B3676CDEA15A897FCB&fenlei=06020204.

Griliches, Z (1990), “Patent Statistics as Economic Indicator: A Survey,” Journal of Economic Literature 28: 1661–1707. http://www.edegan.com/pdfs/Griliches%20(1990)%20-%20Patent%20Statistics%20as%20Economic%20Indicators.pdf.

Guariglia, A., and S. Poncet (2008), “Could Financial Distortions Be No Impediment to Economic Growth after All? Evidence from China,” Journal of Comparative Economics 36: 633–657. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014759670700090X.

King, R. G., and R. Levine (1993), “Finance, Entrepreneurship and Growth: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Monetary Economics 32: 513-542. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/030439329390028E.

Levine, R (2005). “Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence.” In Handbook of Economic Growth. Edited by P. Aghion and S. Durlauf. Netherlands: Elsevier Science. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1574068405010129.

Morales, M. F. (2003), “Financial Intermediation in a Model of Growth through Creative Destruction,” Macroeconomic Dynamics 7: 363–393. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/macroeconomic-dynamics/article/financial-intermediation-in-a-model-of-growth-through-creative-destruction/2ED1FA0DFF819DD109D642525C692557.

Morck, R., and M. Nakamura (1999), “Banks and Corporate Control in Japan,” Journal of Finance 54: 319–340. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/0022-1082.00106/full.

Qian, M., and B. Y. Yeung (2014), “Bank Financing and Corporate Governance,” Journal of Corporate Finance 32: 258–270. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929119914001229.

Shang, H., Q. Y. Song, and Y. Wu (2017), “Credit Market Development and Firm Innovation: Evidence from the People’s Republic of China,” Journal of the Asian and Pacific Economy 22: 71-89. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13547860.2016.1261476 and https://www.adb.org/publications/credit-market-development-and-firm-innovation-evidence-prc.

Solow, R. M (1957), “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function,” Review of Economics and Statistics 39: 312–320. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1926047.

Weinstein, D. E., and Y. Yafeh (1998), “On the Costs of a Bank-centered Financial System: Evidence from the Changing Main Bank Relations in Japan,” Journal of Finance 53: 635–672. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/0022-1082.254893/full.

Zhang, H. (2015), “How Does Agglomeration Promote the Product Innovation of Chinese Firms?”, China Economic Review 35: 105–120. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043951X15000838.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email