Bilateral Trade and Shocks in Political Relations: Evidence from China

To what extent do political relations between countries affect their economic exchange? Using evidence of China’s relations with other major powers during the period of 1990 to 2013, Yingxin Du, Jiandong Ju, Carlos D. Ramirez, and Xi Yao point out the time-aggregation bias in the existing empirical research and provide insights on the relationship between political shocks and trade.

The extent to which shocks in political relations affect trade has been the topic of a significant amount of research not just in economics but also in political science, especially international relations. Many empirical studies find that changes in political relations or certain political events have significant effects on trade between the countries. However, we argue in this column that existing empirical literature on this question has neglected an important issue, specifically, that the variations in political relations nowadays tend to be relatively high-frequency and short-lived. When estimating the extent to which shocks in political relations or political events affect trade, the existing studies usually use data either aggregated or sampled at lower frequencies (for example, quarterly or annually). Because the natural duration of political shocks is shorter than the frequency with which it is measured, using low-frequency data can produce false conclusions regarding whether political shocks affect trade and how large and how long any effect may be.

The temporal aggregation bias

This type of problem is known as the “temporal aggregation” or sampling bias in the time series literature (Granger, 1966, 1969; Marcellino, 1999; Wei, 1982; Breitung and Swanson, 2002; Taylor, 2001; etc.). Researchers found that aggregation (or even averaging) modifies the time series properties of the data at every frequency, removing particular characteristics of the underlying series while simultaneously introducing others. When the important dynamics of political relations that take place within the aggregated intervals are omitted or “smoothed out,” the effect of these high-frequency and short-lived cycles will not be reflected in the estimating results and the estimate will tend to be biased as well (See Note 1).

Dynamics of China’s political relations with other countries

A comprehensive data set measuring China’s political relations with other major powers and some neighboring countries (See Note 2) at the monthly frequency permits our argument to be empirically tested. The data set is constructed by one of China’s leading scholars on international relations, Xuetong Yan and his colleagues (Yan et al, 2010; Yan and Qi, 2009) (See Note 3). We estimate time-series models for the index of political relations between China and countries in this data set for the period of 1990 to 2013. The empirical results show that the natural cycle of the political dynamics in this period tend to be relatively short and high-frequency (See Note 4). After the Cold War, most variability in political relations does not involve the extreme outcome of war. In most cases, foreign relations of China and of many other countries fluctuate along a continuum that ranges from “friendly” to “normal” to “tense,” and occasionally, “threatening” (Davis and Meunier, 2011; Yan et al., 2010). As a result, these political “shocks” tend to be relatively short-lived—coming and going in a matter of months, if not weeks.

The effect of shocks in political relations on bilateral trade

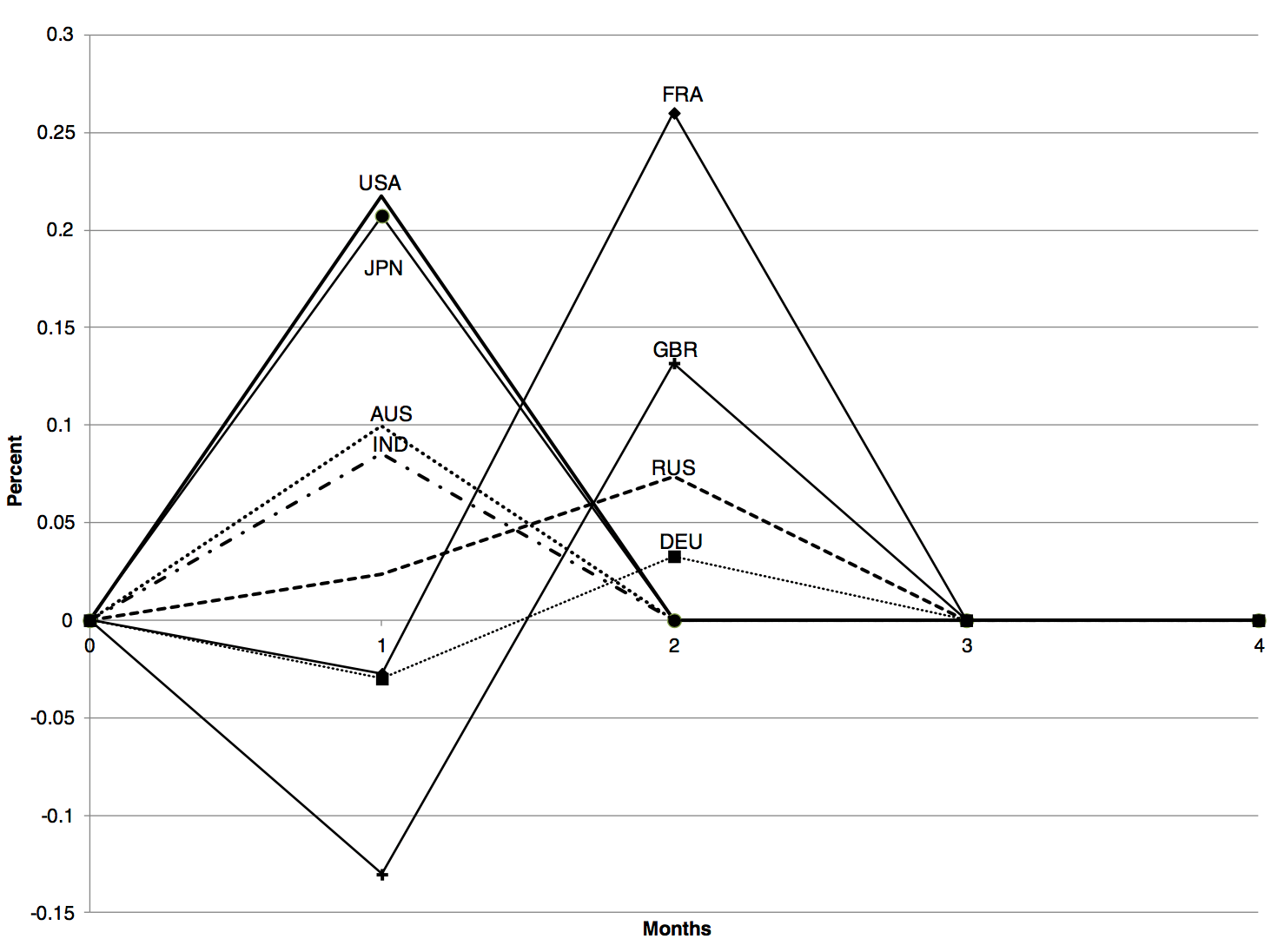

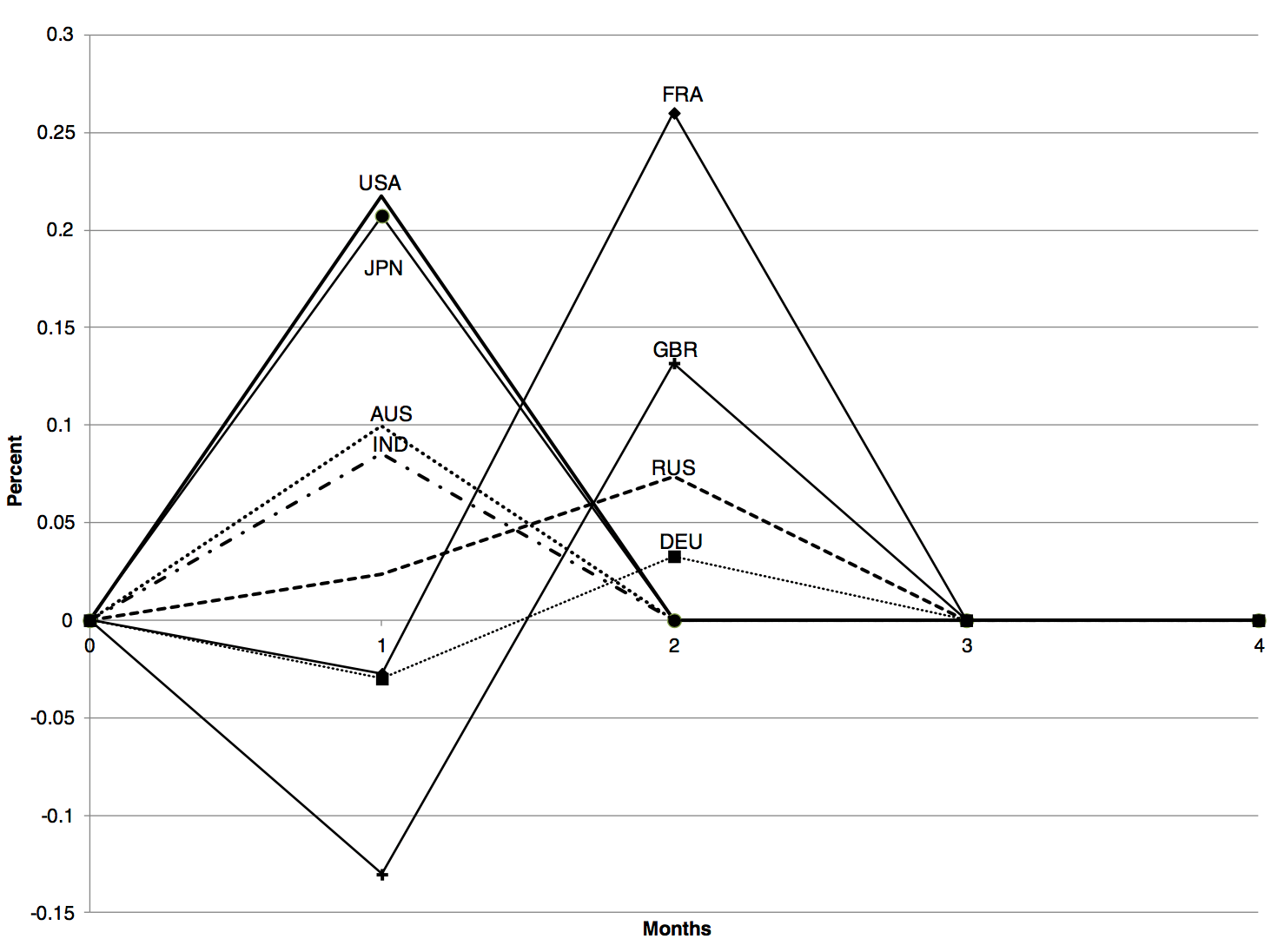

To study to what extent political relations affect trade, one natural way of correcting for the temporal or sampling bias discussed above is to use higher frequency data. We implement a vector auto-regression analysis in which the dynamics between trade and political relations are modeled. The impulse response function shows that following a one-standard-deviation adverse shock to the political relations index, export growth to China (from the partner country) tends to deteriorate in the first month following the shock for about half of the sample, and in month two for the remaining half. After the third month, the effect is essentially nil (Figure 1). No long-term effects are detected. Although political shocks influence exports to China, the effects largely vanish within two months.

Note: For visual clarity, the displayed effects are those that are statistically significant at the 90% level or higher. In no case is the estimated effect significant at month 3 or onward.

Insights on political relations and trade

This finding provides us insights on how we think about political relations and trade. Bilateral trade is a long-term equilibrium determined by the size of the economies, technical efficiency, factor endowments of the trading countries, and similar factors, while unpredictable political shocks are short-term disturbances to the relation between the countries. In a game-theoretic setting, a combination of healthy trade and peaceful political relations can be identified as the “Pareto perfection” equilibrium (such that players will not have the incentive to deviate in any subgame of the equilibrium). When a political shock takes place, thereby threatening the Pareto-dominating equilibrium, players will have an incentive to settle any dispute and restore the superior allocation outcome. In this context, political shocks can be seen as “accidental” deviations from the equilibrium that are rapidly resolved through diplomatic exchanges.

Implications on China

Our empirical findings also substantiate the policy adopted by China for the past few decades. Since 1978, China has adopted a model of “taking economic development as the central task,” while pursuing “an independent foreign policy of peace, a path of peaceful development and a win-win strategy of opening up” (See Note 5). Political frictions between China and other countries will inevitably occur. Many countries regard the rise of China as a political threat. Yet China’s policy of prioritizing economic benefits and economic cooperation implies that China will prevent political disputes from escalating into military conflicts, which will allow a return to a healthy trade and peaceful political relations equilibrium. In this regard, as the empirical findings show, China’s initiative to build a new type of international relations featured by win-win cooperation is not rhetoric but reality.

However, it is worth noting that these empirical findings can be specific to our sample period from 1990 to 2013. Since then, China has entered into a new period of openness, and the relationship between political relations and trade could be different. Political relations may have significant effects on trade in longer horizon in two cases. First, when a country prioritizes its political stance, it is likely that our results no longer hold. Second, existing research has shown that wars can have long-lasting effects on bilateral trade (Che et al., 2015). Therefore, in a period when political relations involve the extreme outcome of war (especially before the Cold War), the dynamics between political relations and trade are expected to have very different patterns. Documenting and modeling the changing dynamics in the new period would be an interesting topic for future research.

Note 1: Our paper provides a mathematical illustration to this bias. We assume that political relations and trade follow a monthly data generation process in the form of a vector-autoregressive model to derive the true process that the aggregated variables follow. The error term turns out to be correlated with the independent variable. As a result, estimating the equation using aggregated data will produce biased estimates.

Note 2: The database includes Australia, France, Germany, India, Japan, Pakistan, Russia, the U.K,, and the U.S.

Note 3: Specifically, a Box-Jenkins analysis reveals that the dynamics of PRI shocks can be modeled with low-order ARIMA processes. This low persistency suggests that political shocks are short-lived. Spectral density analysis shows that high-frequency cycles form an important portion of the dynamics of PRI shocks. This fact underscores the aliasing concern noted by Priestly (1981) —with temporally aggregated series it is not possible to detect important dynamics that are taking place within the aggregated intervals.

Note 4: Specifically, a Box-Jenkins analysis reveals that the dynamics of PRI shocks can be modeled with low-order ARIMA processes. This low persistency suggests that political shocks are short-lived. Spectral density analysis shows that high-frequency cycles form an important portion of the dynamics of PRI shocks. This fact underscores the aliasing concern noted by Priestly (1981) —with temporally aggregated series it is not possible to detect important dynamics that are taking place within the aggregated intervals.

Note 5: Hu Jintao. “Speech at the Meeting Marking the 30th Anniversary of Reform and Opening Up.” 18 Dec. 2008, http://www.bjreview.com.cn/learning/txt/2009-04/27/content_192896.htm. Retrieved Dec. 20, 2016.

Breitung, Jorg, Norman R. Swanson. 2002. “Temporal Aggregation and Spurious Instantaneous Causality in Multiple Time Series Models.” Journal of Time Series Analysis 23 (6), 651–665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9892.00284

Che, Yi, Du Julan, Yi Lu, Zhigang Tao. 2015. “Once an Enemy, Forever an Enemy? The Long-Run Impact of the Japanese Invasion of China from 1937 to 1945 on Trade and Investment.” Journal of International Economics. 96 (1), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.01.001

Granger, Clive W.J. 1966. “The Typical Spectral Shape of an Economic Variable.” Econometrica 34 (1), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1909859

Granger, Clive W.J. 1969. “Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods.” Econometrica 37 (3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912791

Marcellino, Massimiliano. 1999. “Some Consequences of Temporal Aggregation in Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 17 (1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.1999.10524802

Davis, Christina L., Sophie Meunier. 2011. “Business as Usual? Economic Responses to Political Tensions.” American Journal of Political Science. 55 (3), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00507.x

Du, Yingxin, Jiandong Ju, Carlos D. Ramirez, and Xi Yao. 2016. “Bilateral Trade and Shocks in Political Relations: Evidence from China and Some of its Major Trading Partners, 1990–2013.” Journal of International Economics 108 (1): 211-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.07.002

Taylor, Alan M. 2001. “Potential Pitfalls for the Purchasing Power Parity Puzzle? Sampling Specification Biases in Mean-Reversion Tests of the Law of One Price.” Econometrica 69(2):473–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00199

Wei, William W.S. 1982. “The Effects of Systematic Sampling and Temporal Aggregation on Causality—A Cautionary Note.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 77(378):316–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1982.10477806

Yan, Xuetong, and Haixia Qi. 2009. Zhongwaiguanxidingliangyuce [中外关系定量预测; Quantitative Forecasts of China’s Foreign Relations]. Beijing, China: Shijieheshichubanshe.

The extent to which shocks in political relations affect trade has been the topic of a significant amount of research not just in economics but also in political science, especially international relations. Many empirical studies find that changes in political relations or certain political events have significant effects on trade between the countries. However, we argue in this column that existing empirical literature on this question has neglected an important issue, specifically, that the variations in political relations nowadays tend to be relatively high-frequency and short-lived. When estimating the extent to which shocks in political relations or political events affect trade, the existing studies usually use data either aggregated or sampled at lower frequencies (for example, quarterly or annually). Because the natural duration of political shocks is shorter than the frequency with which it is measured, using low-frequency data can produce false conclusions regarding whether political shocks affect trade and how large and how long any effect may be.

The temporal aggregation bias

This type of problem is known as the “temporal aggregation” or sampling bias in the time series literature (Granger, 1966, 1969; Marcellino, 1999; Wei, 1982; Breitung and Swanson, 2002; Taylor, 2001; etc.). Researchers found that aggregation (or even averaging) modifies the time series properties of the data at every frequency, removing particular characteristics of the underlying series while simultaneously introducing others. When the important dynamics of political relations that take place within the aggregated intervals are omitted or “smoothed out,” the effect of these high-frequency and short-lived cycles will not be reflected in the estimating results and the estimate will tend to be biased as well (See Note 1).

Dynamics of China’s political relations with other countries

A comprehensive data set measuring China’s political relations with other major powers and some neighboring countries (See Note 2) at the monthly frequency permits our argument to be empirically tested. The data set is constructed by one of China’s leading scholars on international relations, Xuetong Yan and his colleagues (Yan et al, 2010; Yan and Qi, 2009) (See Note 3). We estimate time-series models for the index of political relations between China and countries in this data set for the period of 1990 to 2013. The empirical results show that the natural cycle of the political dynamics in this period tend to be relatively short and high-frequency (See Note 4). After the Cold War, most variability in political relations does not involve the extreme outcome of war. In most cases, foreign relations of China and of many other countries fluctuate along a continuum that ranges from “friendly” to “normal” to “tense,” and occasionally, “threatening” (Davis and Meunier, 2011; Yan et al., 2010). As a result, these political “shocks” tend to be relatively short-lived—coming and going in a matter of months, if not weeks.

The effect of shocks in political relations on bilateral trade

To study to what extent political relations affect trade, one natural way of correcting for the temporal or sampling bias discussed above is to use higher frequency data. We implement a vector auto-regression analysis in which the dynamics between trade and political relations are modeled. The impulse response function shows that following a one-standard-deviation adverse shock to the political relations index, export growth to China (from the partner country) tends to deteriorate in the first month following the shock for about half of the sample, and in month two for the remaining half. After the third month, the effect is essentially nil (Figure 1). No long-term effects are detected. Although political shocks influence exports to China, the effects largely vanish within two months.

Figure 1: Impulse response function of a PRI shock on exports to China from eight foreign countries

Note: For visual clarity, the displayed effects are those that are statistically significant at the 90% level or higher. In no case is the estimated effect significant at month 3 or onward.

Insights on political relations and trade

This finding provides us insights on how we think about political relations and trade. Bilateral trade is a long-term equilibrium determined by the size of the economies, technical efficiency, factor endowments of the trading countries, and similar factors, while unpredictable political shocks are short-term disturbances to the relation between the countries. In a game-theoretic setting, a combination of healthy trade and peaceful political relations can be identified as the “Pareto perfection” equilibrium (such that players will not have the incentive to deviate in any subgame of the equilibrium). When a political shock takes place, thereby threatening the Pareto-dominating equilibrium, players will have an incentive to settle any dispute and restore the superior allocation outcome. In this context, political shocks can be seen as “accidental” deviations from the equilibrium that are rapidly resolved through diplomatic exchanges.

Implications on China

Our empirical findings also substantiate the policy adopted by China for the past few decades. Since 1978, China has adopted a model of “taking economic development as the central task,” while pursuing “an independent foreign policy of peace, a path of peaceful development and a win-win strategy of opening up” (See Note 5). Political frictions between China and other countries will inevitably occur. Many countries regard the rise of China as a political threat. Yet China’s policy of prioritizing economic benefits and economic cooperation implies that China will prevent political disputes from escalating into military conflicts, which will allow a return to a healthy trade and peaceful political relations equilibrium. In this regard, as the empirical findings show, China’s initiative to build a new type of international relations featured by win-win cooperation is not rhetoric but reality.

However, it is worth noting that these empirical findings can be specific to our sample period from 1990 to 2013. Since then, China has entered into a new period of openness, and the relationship between political relations and trade could be different. Political relations may have significant effects on trade in longer horizon in two cases. First, when a country prioritizes its political stance, it is likely that our results no longer hold. Second, existing research has shown that wars can have long-lasting effects on bilateral trade (Che et al., 2015). Therefore, in a period when political relations involve the extreme outcome of war (especially before the Cold War), the dynamics between political relations and trade are expected to have very different patterns. Documenting and modeling the changing dynamics in the new period would be an interesting topic for future research.

Note 1: Our paper provides a mathematical illustration to this bias. We assume that political relations and trade follow a monthly data generation process in the form of a vector-autoregressive model to derive the true process that the aggregated variables follow. The error term turns out to be correlated with the independent variable. As a result, estimating the equation using aggregated data will produce biased estimates.

Note 2: The database includes Australia, France, Germany, India, Japan, Pakistan, Russia, the U.K,, and the U.S.

Note 3: Specifically, a Box-Jenkins analysis reveals that the dynamics of PRI shocks can be modeled with low-order ARIMA processes. This low persistency suggests that political shocks are short-lived. Spectral density analysis shows that high-frequency cycles form an important portion of the dynamics of PRI shocks. This fact underscores the aliasing concern noted by Priestly (1981) —with temporally aggregated series it is not possible to detect important dynamics that are taking place within the aggregated intervals.

Note 4: Specifically, a Box-Jenkins analysis reveals that the dynamics of PRI shocks can be modeled with low-order ARIMA processes. This low persistency suggests that political shocks are short-lived. Spectral density analysis shows that high-frequency cycles form an important portion of the dynamics of PRI shocks. This fact underscores the aliasing concern noted by Priestly (1981) —with temporally aggregated series it is not possible to detect important dynamics that are taking place within the aggregated intervals.

Note 5: Hu Jintao. “Speech at the Meeting Marking the 30th Anniversary of Reform and Opening Up.” 18 Dec. 2008, http://www.bjreview.com.cn/learning/txt/2009-04/27/content_192896.htm. Retrieved Dec. 20, 2016.

(Yingxin Du, China Institute for WTO Studies, University of International Business and Economics; Jiandong Ju, PBC School of Finance, Tsinghua University; Carlos D. Ramirez, Department of Economics, George Mason University; Xi Yao, Institute of World Economics and Politics, Chinese Academy of Social Science)

Breitung, Jorg, Norman R. Swanson. 2002. “Temporal Aggregation and Spurious Instantaneous Causality in Multiple Time Series Models.” Journal of Time Series Analysis 23 (6), 651–665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9892.00284

Che, Yi, Du Julan, Yi Lu, Zhigang Tao. 2015. “Once an Enemy, Forever an Enemy? The Long-Run Impact of the Japanese Invasion of China from 1937 to 1945 on Trade and Investment.” Journal of International Economics. 96 (1), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.01.001

Granger, Clive W.J. 1966. “The Typical Spectral Shape of an Economic Variable.” Econometrica 34 (1), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1909859

Granger, Clive W.J. 1969. “Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods.” Econometrica 37 (3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912791

Marcellino, Massimiliano. 1999. “Some Consequences of Temporal Aggregation in Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 17 (1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.1999.10524802

Davis, Christina L., Sophie Meunier. 2011. “Business as Usual? Economic Responses to Political Tensions.” American Journal of Political Science. 55 (3), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00507.x

Du, Yingxin, Jiandong Ju, Carlos D. Ramirez, and Xi Yao. 2016. “Bilateral Trade and Shocks in Political Relations: Evidence from China and Some of its Major Trading Partners, 1990–2013.” Journal of International Economics 108 (1): 211-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.07.002

Taylor, Alan M. 2001. “Potential Pitfalls for the Purchasing Power Parity Puzzle? Sampling Specification Biases in Mean-Reversion Tests of the Law of One Price.” Econometrica 69(2):473–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00199

Wei, William W.S. 1982. “The Effects of Systematic Sampling and Temporal Aggregation on Causality—A Cautionary Note.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 77(378):316–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1982.10477806

Yan, Xuetong, and Haixia Qi. 2009. Zhongwaiguanxidingliangyuce [中外关系定量预测; Quantitative Forecasts of China’s Foreign Relations]. Beijing, China: Shijieheshichubanshe.

Yan, Xuetong, Fangyin Zhuo, Haixia Qi, Jin Xu, Zhaijiu Jiang, and Liang Yan. 2010. Zhongwaiguanxijianlan 1950–2005—Zhongguoyudaguoguanxidinglianghengliang [中外关系鉴览1950-2005—中国与大国关系定量衡量; China’s Foreign Relations with Major Powers by the Numbers 1950–2005] Beijing: Gaodengjiaoyuchubanshe.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email