The Role of Punctuation in the P2P Lending Market

Using data from Renrendai, one of the largest P2P lending platforms in China, we investigate how the amount of punctuation used in loan descriptions influences the funding probability, borrowing rate, and default. The empirical evidence shows that the amount of punctuation is negatively associated with the funding probability and borrowing rate. We propose that the usage of punctuation affects the readability of a loan description and reflects borrowers’ self-control and cognitive ability.

With the advance of digital technology, online peer-to-peer (P2P) lending has emerged as an alternative to traditional lending institutions around the world (Greiner & Wang 2010). Bypassing banks, online P2P lending is a special type of credit market in which individual lenders make microloans to individual borrowers without collateral or the intermediation of financial institutions (Lin et al. 2013). Compared with the traditional credit market, online P2P lending is easy to access (Mild et al. 2015), provides a new investment channel, and improves the utilization efficiency of social funds (Duarte et al. 2012). China has developed the biggest and fastest growing market for P2P lending. The volume of P2P lending in China was estimated as high as RMB 225 billion by the end of 2017 (See Note 1).

Yet P2P lending also has disadvantages. There are no financial intermediaries to investigate the credit-worthiness of the borrowers. Both lenders and borrowers are anonymous and don’t ever meet each other. The lenders make their decisions based mainly on the information provided by the borrowers. The most common form of information disclosure across all P2P lending platforms, aside from gender, race, appearance, and social capital, are the loan descriptions written by the borrowers. How this text is written plays a role in determining whether the loan will be approved.

In Chinese, punctuation marks and symbols fulfill the same functions as in any other language. They indicate the structure and organization of the written language, as well as the intonation and pauses to be observed when reading aloud. Punctuation also shows a writer’s personal characteristics and has a significant impact on a reader’s understanding of written language. In P2P lending, the usage of punctuation reflects the borrower’s personality and has a significant impact on the lender’s judgement of the borrower’s trustworthiness.

Using the data obtained from Renrendai, one of the largest P2P lending platforms in China, we investigate the role of punctuation in bridging the information gap between borrowers and lenders. Renrendai is one of the largest peer-to-peer lending platforms in China. Founded in 2010, it now has over 1 million members in more than 2,000 cities and counties across the country. The transactions taking place at Renrendai are typical examples of P2P lending. On the Renrendai lending platform, borrowers can post loan requests with the required information — the loan title, amount to be borrowed, interest rate, description of loan usage, and monthly installment. Renrendai provides verification services with national identification cards, credit reports, and borrowers’ addresses. It assigns a credit score to each borrower according to their borrowing or lending history and the amount of verified information. Renrendai’s profit mainly comes from borrowers’ closing fees and lenders’ servicing fees. To increase the probability of their requests being granted, borrowers may provide personal information such as gender, education, income, marriage status, and so on. Since the verification and credit rating provided by Renrendai are limited, the lenders must determine how trustworthy the borrowers are from the information disclosed on the platform. In particular, borrowers are encouraged to say more about the loan’s purpose and other personal information in a free-form text field called the “loan description.”

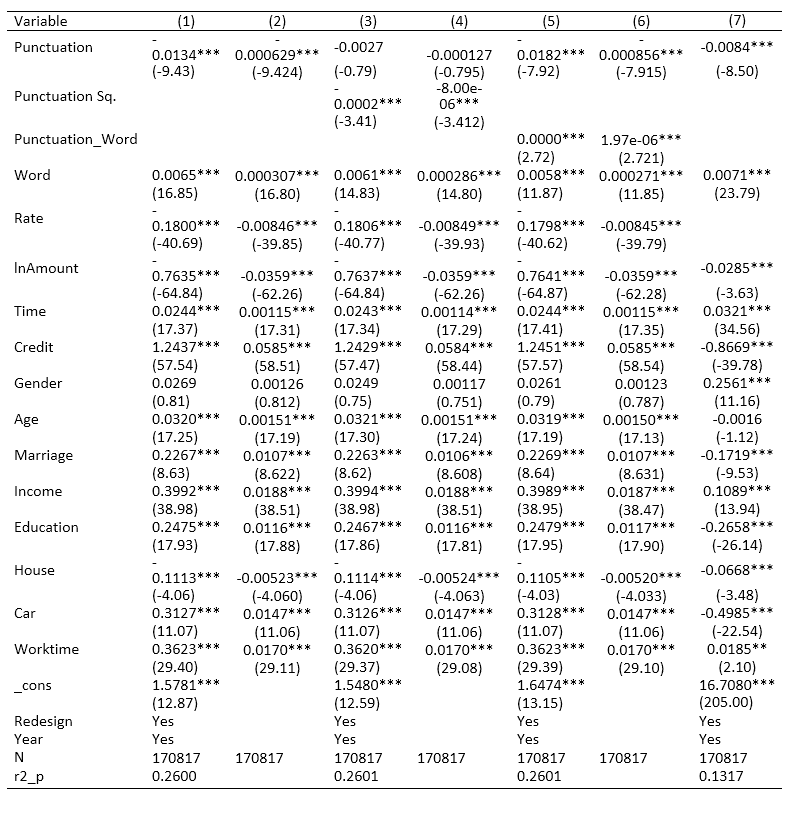

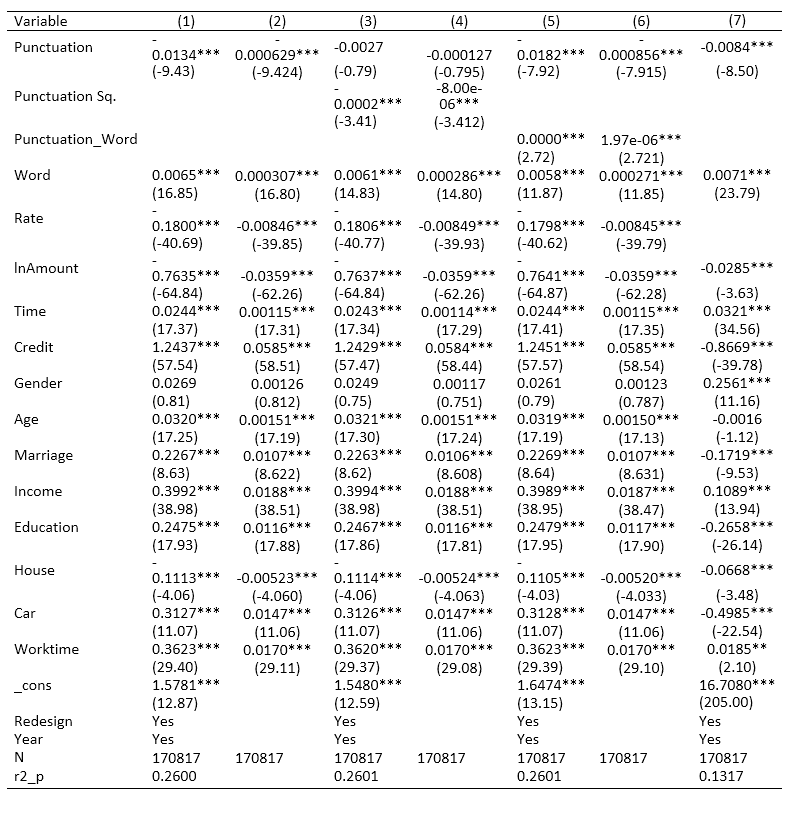

Our study shows that the number of punctuation marks used in the loan description can predict the funding probability and borrowing rate. All else being equal, an additional 10 punctuation marks in the text is associated with a 9.6 percent reduction in the funding possibility. The more punctuation, the less likely a borrower will receive loan approval. Table 1 presents the logistic regression results on the relationship between the number of punctuation marks and the probability of funding success, where a vector of variables, including the number of words in a loan description (Word), logarithm of the borrowing amount (lnAmount), interest rate (Rate), and term (Time), as well as a borrower’s characteristics like credit score (Credit), age (Age), education (Education), income (Income), marriage status (Marriage), working experience (Worktime), home ownership (House), and car ownership (Car) are controlled. Column (1) reports our baseline results while column (2) calculates the relevant marginal effects. In line with existing researches, loan requests with lower interest rates, lower requested amounts, and longer-listing durations are more likely to be funded (Liu et al. 2015; Mild et al. 2015; Dorfleitner et al. 2016; and Lyer et al. 2016). The coefficient on punctuation is negatively significant, implying that more punctuation marks are associated with a lower probability of getting the loan request funded. The marginal effect reported in Column (2) indicates that an additional number of ten punctuation marks is associated with a reduction in the possibility of funding success of 9.6 percentage points (0.000629*10/0.065). Column (3) shows the regression results including the square of the number of punctuation marks as an additional explanatory variable and Column (4) reports the corresponding marginal effects. The negative coefficient on the square of punctuation implies that the funding success rate is linearly-related with the number of punctuation marks as the number of punctuation marks is always positive. The estimated coefficient on “word” is positive, implying that a longer loan description increases the funding success rate by disclosing more information to the investors. To understand the relationship between punctuation and words, we include the interaction term between the number of punctuation marks and the number of words; the estimation results are presented in Column (5). The corresponding marginal effect is shown in Column (6). The positively significant coefficient on the interaction term suggests that the length of the loan description can help moderate the negative effects of punctuation use on the funding success rate. With a larger number of words, the more detailed contents of the loan description will be disclosed. This helps to attenuate information asymmetry between lenders and borrowers. All these results demonstrate that the appropriate usage of punctuation marks indeed predicts the funding probability in the P2P lending market.

Note: The dependent variable is the probability of getting a loan funded for regression (1)-(6) and a borrowing interest rate for regression (7). *p<0.1,**p<0.05,***p<0.001. The Z statistical values are in parentheses.

Our explanations for these empirical findings are as follows. First, the usage of punctuation affects the readability of a loan description. Within a given number of words, excessive usage of punctuation reduces the readability of the text, thereby impairing investors’ trust in borrowers. Second, loan descriptions with an excessive amount of punctuation usually bears the imprint of internet language that is full of slang words. It makes the loan description informal, reduces the readability of text, and impairs the perception of the trustworthiness of the applicants (See Note 2). Undoubtedly, using informal expression in a formal lending market reduces the lender’s trust in a borrower.

Too many punctuation marks may also be interpreted as the borrower having limited self-control or cognitive bias. Self-control affects a person’s consumption and savings and predicts his behavior (Hirshleifer 2001). Informal expression in loan descriptions shape the lender’s judgment of the borrower’s credit-worthiness. Yet some borrowers continue to overuse punctuation possibly because they are overconfident about their loan requests. They usually overreact to private information, overestimate their judgment, and underestimate the risks (Gervais et al. 2011). They also tend to believe that the interest rate they set is correct, when in fact it deviates from the real risk. In Chinese P2P lending platforms, the interest rate is fixed by the borrowers. The investors can only bid on the amount of a loan requested by the borrower. Column (7) of Table 1 presents the estimation results on the relationship between the number of punctuation marks and the borrowing rate. The sign on the punctuation coefficient is -0.0084 and is statistically significant. This suggests that, all else being equal, the interest rate will fall by approximately 0.56% (0.0084*10/14.98) when the number of punctuation marks in the loan description increases by 10.

In conclusion, investors are able to identify credit-worthy borrowers with the help of the punctuation marks used in the loan description even when hard facts like credit scores are not available. Our study has important implications for both the platform operators and participants. To reduce the noise caused by the excessive use of punctuation, platforms should provide guidance for borrowers on how to write their loan descriptions in a formal and standard format.

Note 1: This figure is from https://shuju.wdzj.com/industry-list.html.

Note 2: Here is an example of loan description with overuse of punctuation

本人短期需要资金周转,因刚买了家电和汽车,个人经济有些暂时困难,望能批复下

Dorfleitner, G., C. Priberny, S. Schuster, J. Stoiber, M. Weber, I. de Castro, and J. Kammler, J. 2016. “Description-text Related Soft Information in Peer-to-peer Lending: Evidence from Two Leading European Platforms.” Journal of Banking and Finance 64, 169-187.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378426615003180

Duarte, J., S. Siegel, and L. Young. 2012. “Trust and Credit: The Role of Appearance in Peer-to-peer Lending.” Review of Financial Studies 25:8, 2455-2484.

https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article-abstract/25/8/2455/1570804?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Gervais, S., J. B. Heaton, and T. Odean. 2011. “Overconfidence, Compensation Contracts, and Capital Budgeting.” Journal of Finance 66:5, 1735-1777.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01686.x

Greiner, M. E., and H. Wang. 2010. “Building Consumer-to-consumer Trust in E-finance Marketplaces: An Empirical Analysis.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 15:2, 105-136.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/JEC1086-4415150204

Hirshleifer, D. 2001. “Investor Psychology and Asset Pricing.” Journal of Finance 56:4, 1533-1597.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/0022-1082.00379

Iyer, R., A. I. Khwaja, E. F. P. Luttmer, and K. Shue. 2016. “Screening Peers Softly: Inferring the Quality of Small Borrowers.” Management Science 62:6, 1554-1577.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2181

Lin, M. F., N. R. Prabhala, and S. Viswanathan. 2013. “Judging Borrowers by the Company They Keep: Friendship Networks and Information Asymmetry in Online Peer-to-peer Lending.” Management Science 59:1, 17-35.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1560?journalCode=mnsc

Liu, D., D. J. Brass, Y. Lu, and D. Y. Chen. 2015. “Friendships in Online Peer-to-peer Lending: Pipes, Prisms, and Relational Herding.” MIS Quarterly 39:3, 729-742.

https://misq.org/friendship-in-online-peer-to-peer-lending-pipes-prisms-and-relational-herding.html

Mild, A., M. Waitz, and J. Wockl. 2015. “How Low Can You Go? Overcoming the Inability of Lenders to Set Proper Interest Rates on Unsecured Peer-to-peer Lending Markets.” Journal of Business Research 68:6, 1291-1305.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-business-research/vol/68/issue/6

Peng, L., and W. Xiong. 2006. “Investor Attention, Overconfidence, and Category Learning.” Journal of Financial Economics 80, 563-602.

With the advance of digital technology, online peer-to-peer (P2P) lending has emerged as an alternative to traditional lending institutions around the world (Greiner & Wang 2010). Bypassing banks, online P2P lending is a special type of credit market in which individual lenders make microloans to individual borrowers without collateral or the intermediation of financial institutions (Lin et al. 2013). Compared with the traditional credit market, online P2P lending is easy to access (Mild et al. 2015), provides a new investment channel, and improves the utilization efficiency of social funds (Duarte et al. 2012). China has developed the biggest and fastest growing market for P2P lending. The volume of P2P lending in China was estimated as high as RMB 225 billion by the end of 2017 (See Note 1).

Yet P2P lending also has disadvantages. There are no financial intermediaries to investigate the credit-worthiness of the borrowers. Both lenders and borrowers are anonymous and don’t ever meet each other. The lenders make their decisions based mainly on the information provided by the borrowers. The most common form of information disclosure across all P2P lending platforms, aside from gender, race, appearance, and social capital, are the loan descriptions written by the borrowers. How this text is written plays a role in determining whether the loan will be approved.

In Chinese, punctuation marks and symbols fulfill the same functions as in any other language. They indicate the structure and organization of the written language, as well as the intonation and pauses to be observed when reading aloud. Punctuation also shows a writer’s personal characteristics and has a significant impact on a reader’s understanding of written language. In P2P lending, the usage of punctuation reflects the borrower’s personality and has a significant impact on the lender’s judgement of the borrower’s trustworthiness.

Using the data obtained from Renrendai, one of the largest P2P lending platforms in China, we investigate the role of punctuation in bridging the information gap between borrowers and lenders. Renrendai is one of the largest peer-to-peer lending platforms in China. Founded in 2010, it now has over 1 million members in more than 2,000 cities and counties across the country. The transactions taking place at Renrendai are typical examples of P2P lending. On the Renrendai lending platform, borrowers can post loan requests with the required information — the loan title, amount to be borrowed, interest rate, description of loan usage, and monthly installment. Renrendai provides verification services with national identification cards, credit reports, and borrowers’ addresses. It assigns a credit score to each borrower according to their borrowing or lending history and the amount of verified information. Renrendai’s profit mainly comes from borrowers’ closing fees and lenders’ servicing fees. To increase the probability of their requests being granted, borrowers may provide personal information such as gender, education, income, marriage status, and so on. Since the verification and credit rating provided by Renrendai are limited, the lenders must determine how trustworthy the borrowers are from the information disclosed on the platform. In particular, borrowers are encouraged to say more about the loan’s purpose and other personal information in a free-form text field called the “loan description.”

Our study shows that the number of punctuation marks used in the loan description can predict the funding probability and borrowing rate. All else being equal, an additional 10 punctuation marks in the text is associated with a 9.6 percent reduction in the funding possibility. The more punctuation, the less likely a borrower will receive loan approval. Table 1 presents the logistic regression results on the relationship between the number of punctuation marks and the probability of funding success, where a vector of variables, including the number of words in a loan description (Word), logarithm of the borrowing amount (lnAmount), interest rate (Rate), and term (Time), as well as a borrower’s characteristics like credit score (Credit), age (Age), education (Education), income (Income), marriage status (Marriage), working experience (Worktime), home ownership (House), and car ownership (Car) are controlled. Column (1) reports our baseline results while column (2) calculates the relevant marginal effects. In line with existing researches, loan requests with lower interest rates, lower requested amounts, and longer-listing durations are more likely to be funded (Liu et al. 2015; Mild et al. 2015; Dorfleitner et al. 2016; and Lyer et al. 2016). The coefficient on punctuation is negatively significant, implying that more punctuation marks are associated with a lower probability of getting the loan request funded. The marginal effect reported in Column (2) indicates that an additional number of ten punctuation marks is associated with a reduction in the possibility of funding success of 9.6 percentage points (0.000629*10/0.065). Column (3) shows the regression results including the square of the number of punctuation marks as an additional explanatory variable and Column (4) reports the corresponding marginal effects. The negative coefficient on the square of punctuation implies that the funding success rate is linearly-related with the number of punctuation marks as the number of punctuation marks is always positive. The estimated coefficient on “word” is positive, implying that a longer loan description increases the funding success rate by disclosing more information to the investors. To understand the relationship between punctuation and words, we include the interaction term between the number of punctuation marks and the number of words; the estimation results are presented in Column (5). The corresponding marginal effect is shown in Column (6). The positively significant coefficient on the interaction term suggests that the length of the loan description can help moderate the negative effects of punctuation use on the funding success rate. With a larger number of words, the more detailed contents of the loan description will be disclosed. This helps to attenuate information asymmetry between lenders and borrowers. All these results demonstrate that the appropriate usage of punctuation marks indeed predicts the funding probability in the P2P lending market.

Table 1: Logit Regression Result on Funding Success Rate and Borrowing Rate

Our explanations for these empirical findings are as follows. First, the usage of punctuation affects the readability of a loan description. Within a given number of words, excessive usage of punctuation reduces the readability of the text, thereby impairing investors’ trust in borrowers. Second, loan descriptions with an excessive amount of punctuation usually bears the imprint of internet language that is full of slang words. It makes the loan description informal, reduces the readability of text, and impairs the perception of the trustworthiness of the applicants (See Note 2). Undoubtedly, using informal expression in a formal lending market reduces the lender’s trust in a borrower.

Too many punctuation marks may also be interpreted as the borrower having limited self-control or cognitive bias. Self-control affects a person’s consumption and savings and predicts his behavior (Hirshleifer 2001). Informal expression in loan descriptions shape the lender’s judgment of the borrower’s credit-worthiness. Yet some borrowers continue to overuse punctuation possibly because they are overconfident about their loan requests. They usually overreact to private information, overestimate their judgment, and underestimate the risks (Gervais et al. 2011). They also tend to believe that the interest rate they set is correct, when in fact it deviates from the real risk. In Chinese P2P lending platforms, the interest rate is fixed by the borrowers. The investors can only bid on the amount of a loan requested by the borrower. Column (7) of Table 1 presents the estimation results on the relationship between the number of punctuation marks and the borrowing rate. The sign on the punctuation coefficient is -0.0084 and is statistically significant. This suggests that, all else being equal, the interest rate will fall by approximately 0.56% (0.0084*10/14.98) when the number of punctuation marks in the loan description increases by 10.

In conclusion, investors are able to identify credit-worthy borrowers with the help of the punctuation marks used in the loan description even when hard facts like credit scores are not available. Our study has important implications for both the platform operators and participants. To reduce the noise caused by the excessive use of punctuation, platforms should provide guidance for borrowers on how to write their loan descriptions in a formal and standard format.

Note 1: This figure is from https://shuju.wdzj.com/industry-list.html.

Note 2: Here is an example of loan description with overuse of punctuation

本人短期需要资金周转,因刚买了家电和汽车,个人经济有些暂时困难,望能批复下

(Xiao Chen, Jinan University; Bihong Huang, Asian Development Bank Institute; Dezhu Ye, Jinan University.)

Dorfleitner, G., C. Priberny, S. Schuster, J. Stoiber, M. Weber, I. de Castro, and J. Kammler, J. 2016. “Description-text Related Soft Information in Peer-to-peer Lending: Evidence from Two Leading European Platforms.” Journal of Banking and Finance 64, 169-187.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378426615003180

Duarte, J., S. Siegel, and L. Young. 2012. “Trust and Credit: The Role of Appearance in Peer-to-peer Lending.” Review of Financial Studies 25:8, 2455-2484.

https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article-abstract/25/8/2455/1570804?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Gervais, S., J. B. Heaton, and T. Odean. 2011. “Overconfidence, Compensation Contracts, and Capital Budgeting.” Journal of Finance 66:5, 1735-1777.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01686.x

Greiner, M. E., and H. Wang. 2010. “Building Consumer-to-consumer Trust in E-finance Marketplaces: An Empirical Analysis.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 15:2, 105-136.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/JEC1086-4415150204

Hirshleifer, D. 2001. “Investor Psychology and Asset Pricing.” Journal of Finance 56:4, 1533-1597.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/0022-1082.00379

Iyer, R., A. I. Khwaja, E. F. P. Luttmer, and K. Shue. 2016. “Screening Peers Softly: Inferring the Quality of Small Borrowers.” Management Science 62:6, 1554-1577.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2181

Lin, M. F., N. R. Prabhala, and S. Viswanathan. 2013. “Judging Borrowers by the Company They Keep: Friendship Networks and Information Asymmetry in Online Peer-to-peer Lending.” Management Science 59:1, 17-35.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1560?journalCode=mnsc

Liu, D., D. J. Brass, Y. Lu, and D. Y. Chen. 2015. “Friendships in Online Peer-to-peer Lending: Pipes, Prisms, and Relational Herding.” MIS Quarterly 39:3, 729-742.

https://misq.org/friendship-in-online-peer-to-peer-lending-pipes-prisms-and-relational-herding.html

Mild, A., M. Waitz, and J. Wockl. 2015. “How Low Can You Go? Overcoming the Inability of Lenders to Set Proper Interest Rates on Unsecured Peer-to-peer Lending Markets.” Journal of Business Research 68:6, 1291-1305.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-business-research/vol/68/issue/6

Peng, L., and W. Xiong. 2006. “Investor Attention, Overconfidence, and Category Learning.” Journal of Financial Economics 80, 563-602.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email