Derisking Real Estate in China’s Hybrid Economy

In China’s distinct hybrid economy, which combines market mechanisms with comprehensive state planning and government intervention, the real estate sector holds particular importance, as land sale revenues are a crucial source of funding for local governments, enabling them to finance infrastructure projects and stimulate economic growth. The hybrid structure gives the government a strong commitment and the ability to delay a real estate crisis, but also makes the real estate sector particularly susceptible to policy-related risks.

Over the past three decades, real estate has played a critical role in driving China’s economic growth, with real estate investment contributing approximately 10% of GDP and the real estate and construction sector accounting for over 15% of urban employment (Rogoff and Yang 2021). But China’s real estate sector is now facing a host of challenges. One of the most pressing issues is the debt problem that is plaguing many real estate firms. In 2021, Evergrande, one of the largest real estate companies in China (with a total asset of over 2.3 trillion RMB and a total debt of over 1.9 trillion RMB at the end of 2020) was at the brink of defaulting on some of its debt. This has led to concerns about the stability of the market and the broader financial system. In addition, concerns have been raised about the health of the Chinese real estate market due to drops in real estate prices, an increase in unsold housing inventory in many cities, and a slowdown of the urbanization process, leading to further fears of a broader economic slowdown (Fang et al. 2016, Glaeser et al. 2017). Finally, there are even more general concerns about China’s demographics. In 2022, China’s birth rate dropped below its death rate for the first time. As the population ages and the birth rate decreases, there may be a lack of long-term demand for housing (Rogoff and Yang 2021). All of these challenges are adding to the uncertainty and risk not just in the Chinse economy, but also the potential contagious effects to the global economy.

Xiong (2023) reviews the risks and challenges faced by China’s real estate sector and particularly emphasizes the importance of understanding this sector within the context of China’s hybrid economy. Over the past 40 years, China has adopted many features of free markets, but the government remains heavily involved in using direct and indirect measures to intervene in the economy. The Chinese economy is a mix of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private firms. Although private firms now account for over 70% of urban employment, they mostly operate in peripheral industries. On the other hand, through several rounds of SOE reforms, SOEs have become more profitable and tend to dominate strategically important industries. Moreover, the state continues to set overall direction and goals for the economy through Five-Year Plans and other economic planning. It uses promotion and other career incentives to direct and motivate local governments and SOEs to implement its economic planning. Additionally, incentives such as tax subsidies and financial grants, regulations, and administrative orders are used to guide private firms. This hybrid economy is intended to allow the state to have a strong capacity to intervene during economic downturns and to overcome market externalities, while also capitalizing on the market’s economic efficiencies.

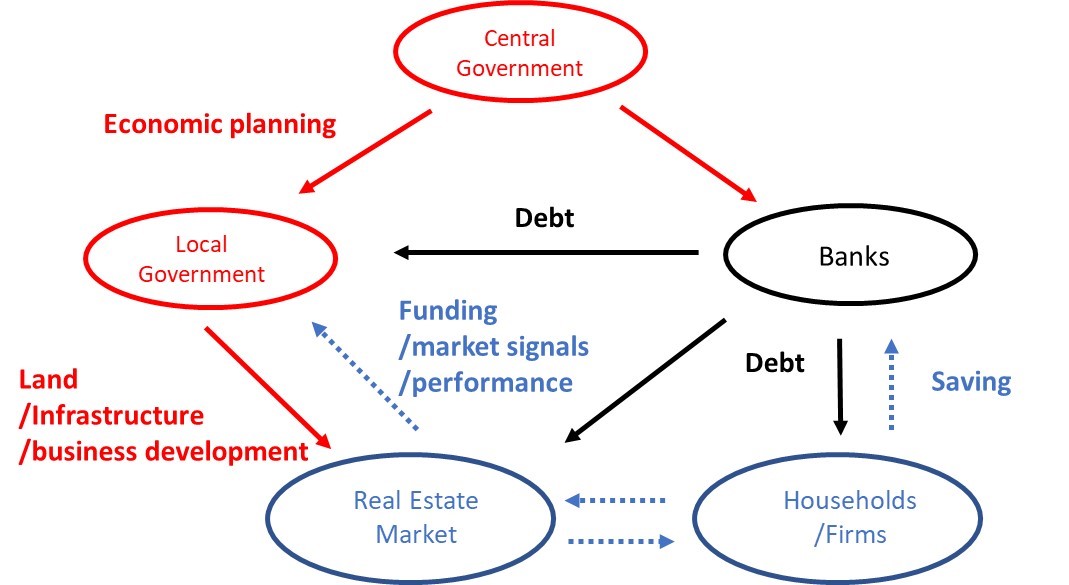

Figure 1: China’s Real Estate Sector

The real estate sector is a vital part of China’s hybrid economy, and the challenges it faces are closely tied to this structure. Figure 1 illustrates the sector’s hybrid structure. The government controls the supply of land, which is the primary input for real estate development, and local governments use revenue from land sales to fund infrastructure and urban development projects. Meanwhile, real estate properties are sold to households and firms in a relatively free market environment. Banks provide debt financing (either directly through bank loans or indirectly by purchasing publicly issued bonds) to all participants in the real estate sector: local governments, which often use future land sale revenues and unsold land as collateral to obtain bank loans; real estate firms, which use land holdings and unsold real estate properties as collateral to finance ongoing projects; households, which take mortgage loans to finance their housing purchases; and firms, which use real estate properties as collateral to finance their real estate purchases or other investments.

This hybrid structure allows the local government to provide infrastructure and public goods, facilitating local businesses and boosting economic growth and development. The real estate market provides feedback to the government’s development plan, allowing it to respond to market signals and make informed decisions about urban development and local businesses. Moreover, the market serves as a mechanism to hold the government accountable for implementing its development plan. When this hybrid model functions optimally, state intervention and the market complement each other, balancing market externalities and promoting economic efficiency. However, if the interactions between these two forces are not appropriately managed, they may exacerbate market externalities and undermine economic efficiency.

The hybrid structure may lead to overinvestment and overleverage in China’s real estate sector due to several forces. Firstly, local governments are responsible for implementing the central government’s economic and social policies, with land sales being a crucial source of fiscal funding. Therefore, the central government’s policy agenda can significantly impact the real estate sector through its role as the financing channel of local governments, even if the policies are not directly related to real estate. Secondly, local government officials are incentivized by the central government’s evaluations of their job performance, which can create short-term incentives for local governments to overinvest in infrastructure to boost local economies and overspend in projects mandated by the central government. These short-term incentives can create funding pressures that lead to incentives to boost local real estate markets so that local governments can sell more land at higher prices.

These short-term incentives are particularly concerning when local governments can use debt financing. Although the central government prohibited local governments from using debt financing before 2008 to discipline the “soft budget problem” of local governments, it granted local governments access to debt financing to implement China’s massive post-crisis stimulus in 2008–2010. Since then, local governments have increasingly used debt to finance their operations. The debt financing used by local governments is typically collateralized by future land sales, land, or real estate properties and is typically in the form of bank loans and public debt directly taken by local governments or indirectly through local government financing vehicles.

Real estate–related debt accounts for about 25% of banks’ assets in China, and around half of it is connected to local governments, according to Liu and Xiong (2020). Such heavy exposure of banks to the real estate sector makes it systemically important. If a real estate crash were to occur, it could lead to significant bank losses and even trigger a banking crisis. This situation creates an environment where the real estate sector is seen as “too big to fail.” Therefore, both central and local governments feel pressure to provide implicit and explicit guarantees to protect the sector from a potential crash. When the real estate market is under distress, the central government may adjust macroeconomic and monetary policies and loosen mortgage requirements to support it, while local governments may take direct measures to prevent real estate prices from falling. During real estate downturns, it is common for local governments to remove restrictions on investment home purchases. In some cases, local governments have even issued administrative orders to prohibit real estate firms from reducing residential housing prices below certain limits, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The explicit or implicit guarantees provided by the government create moral hazard and distortions in both state intervention and the market, thus providing a third channel for overinvestment and overleverage in the real estate sector. With the guarantees from the central government, local governments may be more inclined to use real estate–collateralized debt to boost their short-term performance, further exacerbating the soft-budget problem. Such short-term behaviors may prioritize real estate development over other areas of economic growth, exacerbating local governments’ incentives to deliver their development plans. Furthermore, anticipating both central and local governments’ incentives to protect the real estate market, real estate firms may have incentives to overbuild real estate properties, and households and non-real estate firms may engage in reckless real estate speculation. Such speculation may distort market prices and reduce the informativeness of real estate prices as market signals. Adding these distortions together, state intervention and the market can exacerbate each other and amplify externalities in the real estate sector, ultimately jeopardizing the sector’s financial stability and worsening the economic efficiency of the wider economy.

The hybrid structure of China’s real estate market means that its risks are distinct from those faced by the US real estate market in the mid-2000s. The decline of the US real estate market in 2006 led to the failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008 and eventually to a full-blown global financial crisis. Coordination failure, as identified by the seminal work of three Nobel laureates—Diamond and Dybvig (1983) on a theory of bank runs, and Bernanke (2018) on a diagnosis of the 2008 World Financial Crisis—is one the root causes of financial crises in market economies. When some depositors rush to exit by cashing out, forced liquidation may lead to an otherwise healthy bank’s failure, and the cascading effects may drag down other healthy financial institutions, leading to a systemwide financial crisis.

The Chinese government’s commitment to financial stability and ability to mobilize local governments, state banks, and SOEs make a Western-style debt crisis less likely. The recent example of the Evergrande crisis showed the government’s determination and capacity to prevent a potential financial crisis by privately instructing local governments to sort out Evergrande’s financial situation and organizing a partial bailout through state-owned banks and firms. Given the vital importance of the real estate sector to the Chinese economy, it is expected that the government will intervene to prevent a financial meltdown and mitigate a hard landing of the market in any future real estate crisis.

While government intervention can help postpone the disruption of a financial crisis, it may not resolve the structural challenges faced by the real estate sector, which is a crucial part of the Chinese economy. A slowdown in this sector could have significant spillover effects on related industries, such as construction, manufacturing, and finance. This could lead to a decline in economic growth, job losses, and reduced consumer confidence, which could further dampen economic growth. Moreover, if the government uses too much stimulus to prop up the real estate market, it could lead to other economic problems in the long run, such as misallocation of capital, inflation, and financial instability. Ultimately, the risk of the real estate sector in China is the economic growth risk, which encompasses the broader effects of a potential real estate downturn on the country’s economic growth, employment, and stability.

A real estate downturn is particularly difficult for China’s hybrid economy, as the country has previously relied on government-led infrastructure investments to spur economic growth during such events. Local governments depend heavily on revenue from land sales to fund public infrastructure and social services, including the extensive COVID-19 lockdown policies. In recent years, land sales have accounted for approximately 40% of their total revenue. Thus, a slowdown in the real estate market not only creates substantial pressure on the economy, but also limits the fiscal capacity of local governments to stimulate economic growth.

Ultimately, the way to derisk China’s real estate sector is to find new growth engines for the country’s economy. Over the past few decades, the real estate sector has been a significant contributor to China’s economic growth. However, as the sector faces mounting challenges and risks, policymakers must look for new sources of growth. One proposed solution is to transform the economy to be driven more by internal consumption than exports. In addition to finding new growth engines, policymakers must find a new financing model for local governments, replacing the reliance on land sale revenues. This could involve exploring alternative sources of revenue for local governments, such as property taxes or other forms of taxation.

The hybrid structure of the real estate sector makes it particularly vulnerable to policy risks. If the central government sets overly ambitious growth targets, local officials may be pressured to rely on land sales or debt financing to fund more infrastructure projects, exacerbating the already high leverage and debt levels of both local governments and real estate developers. This could lead to further systemic risks and worsen economic efficiency.

The extensive state interventions to maintain financial stability resemble the strategy of binding boats together to weather a storm, famously employed by the northern army of Cao Cao at the Battle of Chibi in AD 208–209 during the Three Kingdoms period in ancient China. However, this strategy also exposes the entire system to an unforeseen fire that could simultaneously burn all boats. In other words, if a shock were to ultimately trigger an economic collapse within the Chinese economy, the real estate sector might amplify the shock and collapse along with the economy.

Therefore, it is crucial that the central government takes a prudent and sustainable approach to managing the economy and the real estate sector, prioritizing the stability and sustainability of both over short-term economic and political goals. Structural transformation into a more consumption-driven economy, investing in new growth engines, and promoting a more balanced supply-demand relationship in the real estate sector can create a stable and sustainable economic environment that benefits all stakeholders and thus gradually reduces risk in the sector.

References

Bernanke, Ben S. 2018. “The Real Effects of Disrupted Credit: Evidence from the Global Financial Crisis.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 49 (2): 251–342. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Bernanke_final-draft.pdf.

Diamond, Douglas W., and Philip H. Dybvig. 1983. “Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity.” Journal of Political Economy 91 (3): 401–19. https://doi.org/10.1086/261155.

Fang, Hanming, Quanlin Gu, Wei Xiong, and Li-An Zhou. 2016. “Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom.” In NBER Macroeconomics Annual, vol. 30, edited by Martin Eichenbaum and Jonathan Parker, 105–66. https://doi.org/10.1086/685953.

Glaeser, Edward, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, and Andrei Shleifer. 2017. “A Real Estate Boom with Chinese Characteristics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31 (1): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.1.93.

Liu, Chang, and Wei Xiong. 2020. “China’s Real Estate Market.” In The Handbook of China’s Financial System, edited by Marlene Amstad, Guofeng Sun, and Wei Xiong, 181–207. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rogoff, Kenneth, and Yuanchen Yang. 2021. “Has China’s Housing Production Peaked?” China and World Economy 29 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12360.

Xiong, Wei. 2023. “Derisking Real Estate in China’s Hybrid Economy.” In The Arc of Chinese Economy, forthcoming.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email