The Future of Cities: The Shanghai Model of Migrant Children’s Education

Using a longitudinal survey conducted by the authors in Shanghai since 2010, we empirically examine the differences between migrant schools and public schools. We find that migrant students in migrant schools performed substantially worse than their counterparts in public schools in 2010, but the difference decreased by half in 2012, thanks to financial subsidies to migrant schools. We also show that even fortunate migrant students who are able to enroll in public schools tend to go to poorer quality schools; however, there is no evidence on negative peer effects of migrant children in public schools.

As a consequence of China’s rapid and large-scale urbanization, a significant proportion of rural peasants have migrated to cities to work. Around 12.7 million of the migrants are school-age children, according to a report by the Ministry of Education. Therefore, the accommodation of the educational needs of those migrant children has been a major challenge in the urbanization process. Since 2010, we have conducted a large longitudinal survey of around 3,000 students in 20 elementary schools in Shanghai, which keeps track of these students from their 4th grade year in the elementary school to their middle school graduation. This book, The Future of Cities: The Shanghai Model of Migrant Children's Education, summarizes our empirical findings based on this data set.

Background

Before 2001, migrant children were not entitled to enter local public schools because compulsory education is based on the one’s “hukou”, or the place of official residence registration. Only a small proportion of migrant children managed to enter public schools, mostly by paying an expensive extra fee. The rest of the migrant children had to enter lower-quality private migrant schools. Since 2001, the central government has urged the host city governments to be responsible for the education of migrant children. As a result, the proportion of migrant children entering public schools has increased. As of 2012, around 88% of migrant children are enrolled in public schools in Beijing, 70% in Shanghai, 41% in Guangzhou, and 46% in Shenzhen. Nevertheless, as spaces in public schools are still limited, there are still a substantial number of migrant children in private migrant schools.

Our study focuses in Shanghai, which is one of the largest migrant-receiving cities in China. Among all major cities, Shanghai was among the most accommodating ones in terms of meeting migrant children’s education needs during the period from 2008 to 2013. In 2008, the Shanghai government launched a “three-year action plan for the education of migrant children,” which was characterized by further opening-up of public schools to migrant children and subsidizing them. In Shanghai’s central districts, all migrant schools were shut down and migrant students in these districts were transferred to public schools. In peripheral districts, as there were not enough public schools for all migrant children, the government allowed migrant schools to continue to operate and provided subsidies so that no tuition was charged to migrant students.

Since then, Shanghai’s government has increased both financial and administrative support for migrant schools. In terms of financial support, the per pupil subsidy has increased from RMB2,000 in 2008 to RMB4,500 in 2010 to RMB5,000 in 2012. Although it represents only around one-third to one-fourth of the per pupil funding for public schools, such subsidies are sufficient to cover the wages of teachers and daily operating expenses of migrant schools. In terms of administrative support, local district education bureaus have given more training opportunities to teachers in migrant schools and have conducted more demanding monitoring programs, including annual check-ups.

Main Findings

In our book, we focus on migrant schools and their differences with public schools. We have carefully analyzed the differences among local Shanghai students, migrant students in public schools, and migrant students in migrant schools, in terms of school characteristics, class and teachers’ characteristics, students’ performance in various dimensions, teachers' evaluations of students, family backgrounds, and parental expectations. Here, we only outline some key findings of the book.

(1) School type is a key determinant of migrant children’s academic performance

We first study to what extent entering public schools can help improve the academic performance of migrant students using data from the 2010 round of the survey (see also Chen and Feng, 2013). Since there are substantial nonrandom selections into public schools, we chose parents’ residence in 2008 as the instrument variable to control for endogeneity bias. This date was appropriate because the Shanghai government officially launched the “three-year action plan for the education of migrant children” at the end of 2008, which resulted in a complete shut-down of migrant schools in all central districts by 2011. Therefore, if a migrant lived in a central district of Shanghai in 2008, then the probability of her child enrolling in a public school would be much higher than if she lived in a peripheral district in 2008. In other words, our identification strategy utilizes the geographic variation (central versus peripheral districts) in school types that are caused by exogenous policy changes.

Our results suggest that school type is one of the most important determinants of the test score gap between migrant students in migrant schools and migrant students in public schools. It also accounts for a significant share of the overall gap between all migrant students and all local Shanghai students. Taking this at face value, if all migrant students in migrant schools were reassigned to public schools, then the overall test score gap between migrant students and local Shanghai students would shrink from 9.7 to 6 for Chinese (a 3.7 point decrease), and from 13.6 to 8.3 for mathematics (a 5.3 point decline), where the same tests are given to all students with the perfect score being 100. On the other hand, if we give all migrant students the same family background (family monthly income, father’s education, and mother’s education) as local Shanghai students, test score gaps for Chinese and mathematics would shrink by only 1.3 points and 4.8 points, respectively.

(2) The quality of migrant schools has improved over time, thanks to increased government financial support

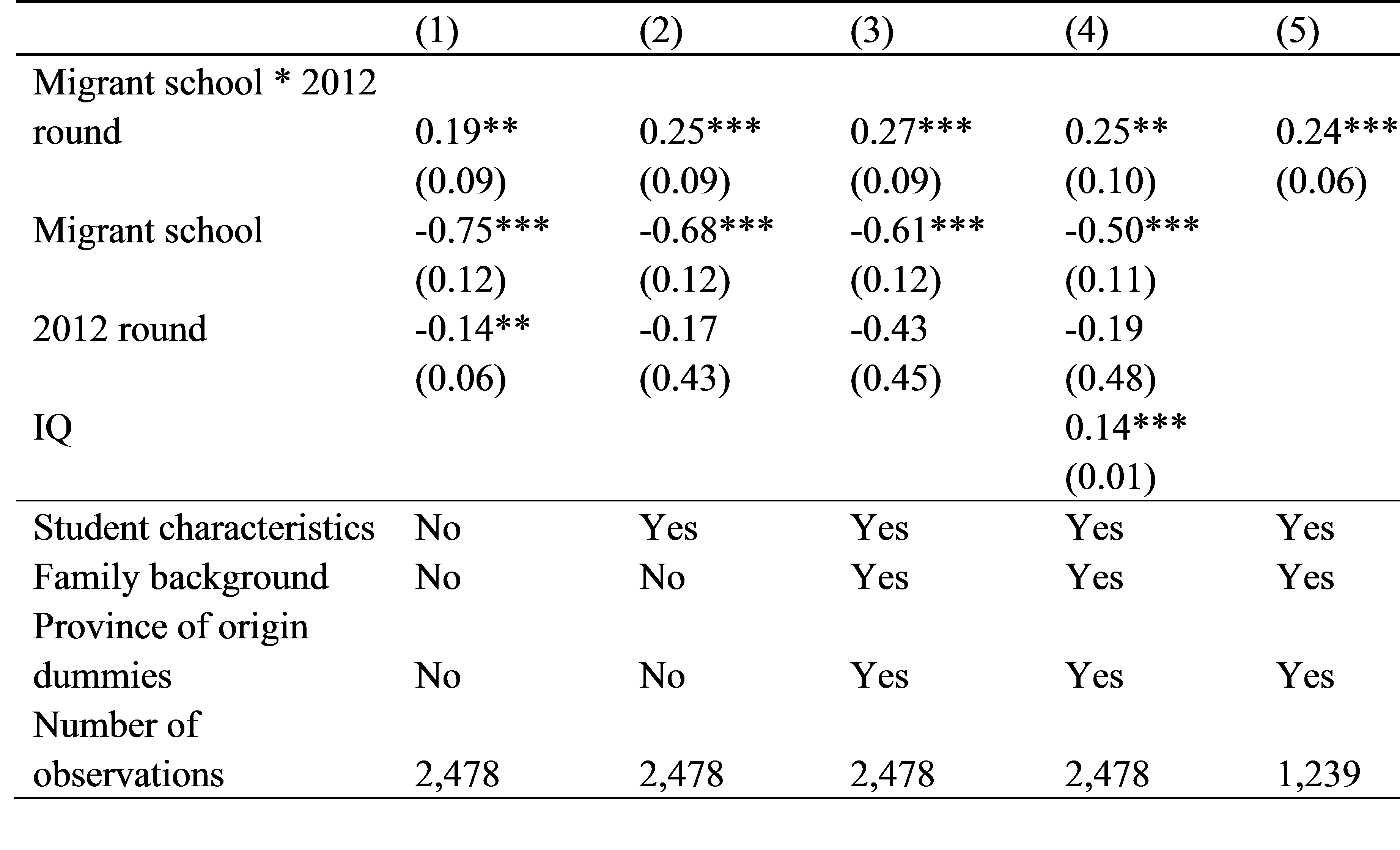

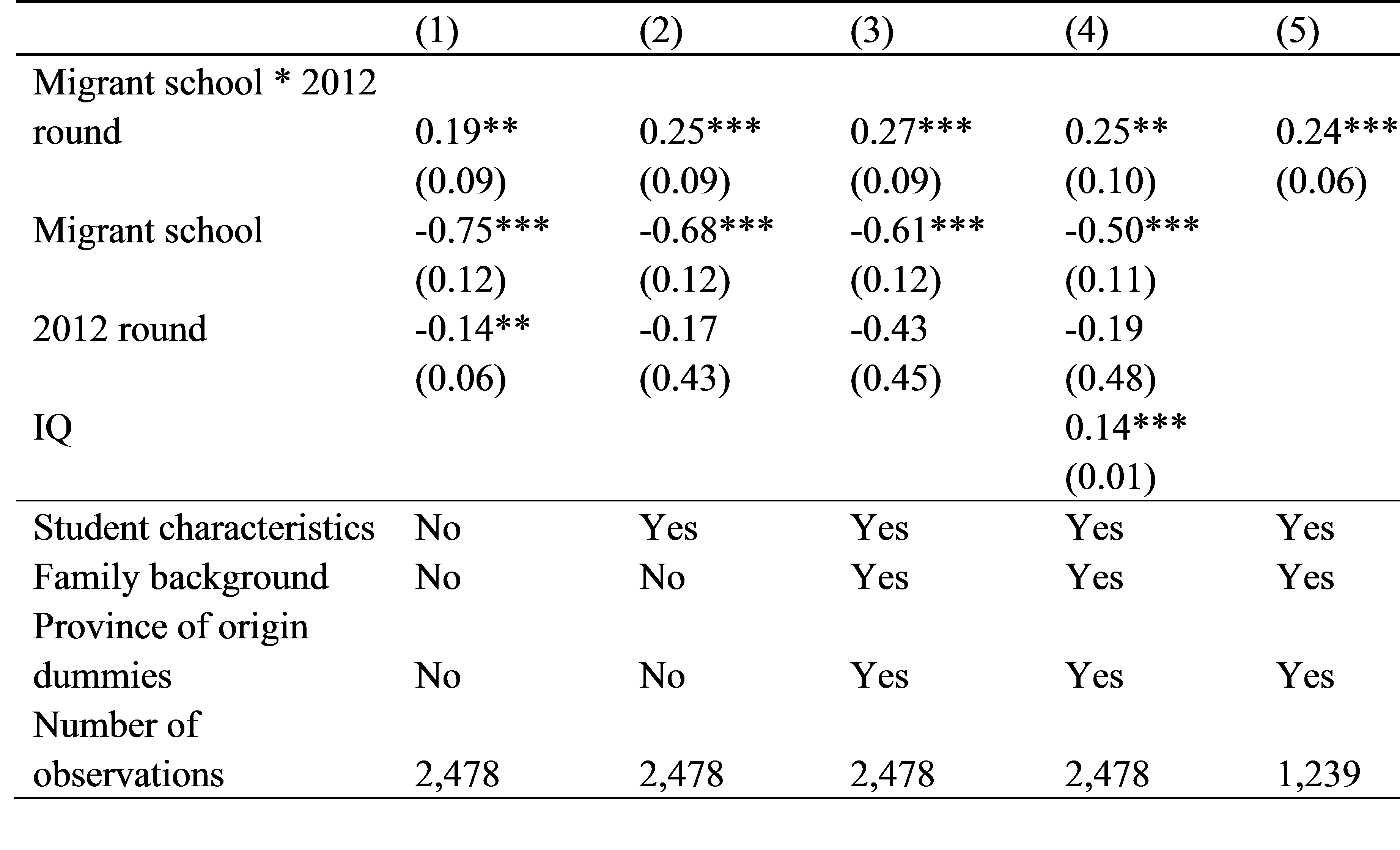

We then combine data from the 2010 round survey with a follow-up survey conducted in 2012 to evaluate whether the quality of migrant schools has significantly improved as the government increased its financial subsidies (Chen and Feng, 2017). We find that the test score difference between public schools and migrant schools in mathematics was almost halved between 2010 and 2012, as shown in Table 1. Column 4 shows our preferred specification, where we control for IQ in addition to various student and family characteristics. The difference-in-difference estimate is 0.25, which means that migrant children in migrant schools have improved relative to those students in public schools by a one-quarter standard deviation in math scores. Given that the initial difference was 0.5 as shown in column 4, this means that the test score difference was reduced by 50%. The estimate is quite robust, as it hardly changes when we use a student fixed effect model, shown in column 5 of Table 1. In addition, parental subjective evaluations of migrant school quality have also improved relative to those of the public schools.

We argue that such improvements are unlikely to be driven by changes on the part of students and parents, but rather reflect genuine relative quality upgrading of migrant schools. We associate such improvements to policies adopted by the Shanghai government toward migrant schools since 2008, especially the sharp increase in the level of financial subsidies in 2010, which allows schools to keep better teachers and properly incentivize them. We also performed a falsification test with two new waves of data of a new cohort of students for the years 2015 and 2016, encompassing a period with no changes in financial subsidies. The new data reveal no relative changes in the performance of migrant school students, thus lending additional support to our main hypothesis.

Table 1. Math score gap between migrant students in public schools and migrant schools in 2010 & 2012

Note: Numbers reported in parentheses are robust standard errors clustered at the class level. ***, **, * stand for statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. Wave 2 dummy is also interacted with all other variables but results are not included in the Table. Student characteristics include age in month, rural hukou, gender, single child, ever attending kindergarten, and daily time spent for homework. Family background variables include parental migration duration, parental education, occupation, and family income.

Our result is probably unsurprising given that migrant schools have very low levels of resources to start with, which implies that the marginal return of increased investments is relatively large. Given that other big cities, such as Beijing and Guangzhou, have provided essentially no financial support to migrant schools, Shanghai's experience seems remarkable and should serve as a model to other cities.

(3) Migrant students perform equally well as local students in the same public schools

Last but not least, we further compare migrant student performance to local “hukou” students and we find that within schools, migrant students perform as well as their local peers. Specifically, we do not find significant differences between migrant and local students in terms of their standardized math test scores, teachers’ evaluations, the probability of being class leaders, and self-reported psychological behaviors. Meanwhile, we find no evidence of discrimination toward migrant students within schools.

Within school comparison, however, does not reflect the whole picture of the education situation of migrant students, as school choices are not random even among public schools. There might be a sorting of students based on family background to schools with different qualities. To examine this, we construct a school quality index and confirm that for both migrant and local students, those with a better family background are sorted into higher-quality schools. In addition, we also find that migrant students are less likely to enter better public schools.

Sorting across schools occurs as parents with better socio-economic backgrounds make extra effort to enroll their children into higher-quality schools or with lower ratios of migrant students. The latter happens when parents, especially local parents, think that migrant student classmates would exert negative peer effects on other children. Therefore, it is important to examine whether exposure to a higher fraction of migrant students causes lower student achievement. We find that the proportion of migrant students is negatively correlated with school average test scores, but this correlation is mainly due to the difference in school quality and student family background. We do not find evidence of a negative peer effect of migrant students either at the school level or the class level.

Outlook

In terms of public policy, our results suggest that to improve the educational prospects of migrant children, governments should do two things. First, they should allow more migrant students to enroll in public schools and especially the higher-quality public schools. Second, they should also help migrant schools improve through offering more financial subsidies to offer a level playing field. What happened in Shanghai since 2010 shows that these are feasible and effective options for other cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen to consider.

However, since 2013, there have been stricter population controls in super-cities. Shanghai, without exception, has dramatically strengthened various population control measures, including imposing more stringent school enrollment requirements on migrant students. As a result, school enrollments of migrant students in Shanghai decreased sharply from 2013 to 2014 and remained at a much lower level than before. We argue that this is not a virtuous education policy, as many students were forced to go back to their home villages and became "left-behind children;" some even had to drop out of school. On the other hand, this may not be a very effective population control policy, as many parents stayed in the city to work while separated from their children.

Chen, Yuanyuan and Shuaizhang, Feng, “Quality of migrant schools in China: evidence from a longitudinal study in Shanghai,” Journal of Population Economics, 2017(30), 1007-1034. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-016-0629-5.

Chen, Yuanyuan and Shuaizhang, Feng, “Access to public schools and the education of migrant children in China,” China Economic Review 26, 2013, 75-88. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043951X13000400.

As a consequence of China’s rapid and large-scale urbanization, a significant proportion of rural peasants have migrated to cities to work. Around 12.7 million of the migrants are school-age children, according to a report by the Ministry of Education. Therefore, the accommodation of the educational needs of those migrant children has been a major challenge in the urbanization process. Since 2010, we have conducted a large longitudinal survey of around 3,000 students in 20 elementary schools in Shanghai, which keeps track of these students from their 4th grade year in the elementary school to their middle school graduation. This book, The Future of Cities: The Shanghai Model of Migrant Children's Education, summarizes our empirical findings based on this data set.

Background

Before 2001, migrant children were not entitled to enter local public schools because compulsory education is based on the one’s “hukou”, or the place of official residence registration. Only a small proportion of migrant children managed to enter public schools, mostly by paying an expensive extra fee. The rest of the migrant children had to enter lower-quality private migrant schools. Since 2001, the central government has urged the host city governments to be responsible for the education of migrant children. As a result, the proportion of migrant children entering public schools has increased. As of 2012, around 88% of migrant children are enrolled in public schools in Beijing, 70% in Shanghai, 41% in Guangzhou, and 46% in Shenzhen. Nevertheless, as spaces in public schools are still limited, there are still a substantial number of migrant children in private migrant schools.

Our study focuses in Shanghai, which is one of the largest migrant-receiving cities in China. Among all major cities, Shanghai was among the most accommodating ones in terms of meeting migrant children’s education needs during the period from 2008 to 2013. In 2008, the Shanghai government launched a “three-year action plan for the education of migrant children,” which was characterized by further opening-up of public schools to migrant children and subsidizing them. In Shanghai’s central districts, all migrant schools were shut down and migrant students in these districts were transferred to public schools. In peripheral districts, as there were not enough public schools for all migrant children, the government allowed migrant schools to continue to operate and provided subsidies so that no tuition was charged to migrant students.

Since then, Shanghai’s government has increased both financial and administrative support for migrant schools. In terms of financial support, the per pupil subsidy has increased from RMB2,000 in 2008 to RMB4,500 in 2010 to RMB5,000 in 2012. Although it represents only around one-third to one-fourth of the per pupil funding for public schools, such subsidies are sufficient to cover the wages of teachers and daily operating expenses of migrant schools. In terms of administrative support, local district education bureaus have given more training opportunities to teachers in migrant schools and have conducted more demanding monitoring programs, including annual check-ups.

Main Findings

In our book, we focus on migrant schools and their differences with public schools. We have carefully analyzed the differences among local Shanghai students, migrant students in public schools, and migrant students in migrant schools, in terms of school characteristics, class and teachers’ characteristics, students’ performance in various dimensions, teachers' evaluations of students, family backgrounds, and parental expectations. Here, we only outline some key findings of the book.

(1) School type is a key determinant of migrant children’s academic performance

We first study to what extent entering public schools can help improve the academic performance of migrant students using data from the 2010 round of the survey (see also Chen and Feng, 2013). Since there are substantial nonrandom selections into public schools, we chose parents’ residence in 2008 as the instrument variable to control for endogeneity bias. This date was appropriate because the Shanghai government officially launched the “three-year action plan for the education of migrant children” at the end of 2008, which resulted in a complete shut-down of migrant schools in all central districts by 2011. Therefore, if a migrant lived in a central district of Shanghai in 2008, then the probability of her child enrolling in a public school would be much higher than if she lived in a peripheral district in 2008. In other words, our identification strategy utilizes the geographic variation (central versus peripheral districts) in school types that are caused by exogenous policy changes.

Our results suggest that school type is one of the most important determinants of the test score gap between migrant students in migrant schools and migrant students in public schools. It also accounts for a significant share of the overall gap between all migrant students and all local Shanghai students. Taking this at face value, if all migrant students in migrant schools were reassigned to public schools, then the overall test score gap between migrant students and local Shanghai students would shrink from 9.7 to 6 for Chinese (a 3.7 point decrease), and from 13.6 to 8.3 for mathematics (a 5.3 point decline), where the same tests are given to all students with the perfect score being 100. On the other hand, if we give all migrant students the same family background (family monthly income, father’s education, and mother’s education) as local Shanghai students, test score gaps for Chinese and mathematics would shrink by only 1.3 points and 4.8 points, respectively.

(2) The quality of migrant schools has improved over time, thanks to increased government financial support

We then combine data from the 2010 round survey with a follow-up survey conducted in 2012 to evaluate whether the quality of migrant schools has significantly improved as the government increased its financial subsidies (Chen and Feng, 2017). We find that the test score difference between public schools and migrant schools in mathematics was almost halved between 2010 and 2012, as shown in Table 1. Column 4 shows our preferred specification, where we control for IQ in addition to various student and family characteristics. The difference-in-difference estimate is 0.25, which means that migrant children in migrant schools have improved relative to those students in public schools by a one-quarter standard deviation in math scores. Given that the initial difference was 0.5 as shown in column 4, this means that the test score difference was reduced by 50%. The estimate is quite robust, as it hardly changes when we use a student fixed effect model, shown in column 5 of Table 1. In addition, parental subjective evaluations of migrant school quality have also improved relative to those of the public schools.

We argue that such improvements are unlikely to be driven by changes on the part of students and parents, but rather reflect genuine relative quality upgrading of migrant schools. We associate such improvements to policies adopted by the Shanghai government toward migrant schools since 2008, especially the sharp increase in the level of financial subsidies in 2010, which allows schools to keep better teachers and properly incentivize them. We also performed a falsification test with two new waves of data of a new cohort of students for the years 2015 and 2016, encompassing a period with no changes in financial subsidies. The new data reveal no relative changes in the performance of migrant school students, thus lending additional support to our main hypothesis.

Table 1. Math score gap between migrant students in public schools and migrant schools in 2010 & 2012

Note: Numbers reported in parentheses are robust standard errors clustered at the class level. ***, **, * stand for statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. Wave 2 dummy is also interacted with all other variables but results are not included in the Table. Student characteristics include age in month, rural hukou, gender, single child, ever attending kindergarten, and daily time spent for homework. Family background variables include parental migration duration, parental education, occupation, and family income.

Our result is probably unsurprising given that migrant schools have very low levels of resources to start with, which implies that the marginal return of increased investments is relatively large. Given that other big cities, such as Beijing and Guangzhou, have provided essentially no financial support to migrant schools, Shanghai's experience seems remarkable and should serve as a model to other cities.

(3) Migrant students perform equally well as local students in the same public schools

Last but not least, we further compare migrant student performance to local “hukou” students and we find that within schools, migrant students perform as well as their local peers. Specifically, we do not find significant differences between migrant and local students in terms of their standardized math test scores, teachers’ evaluations, the probability of being class leaders, and self-reported psychological behaviors. Meanwhile, we find no evidence of discrimination toward migrant students within schools.

Within school comparison, however, does not reflect the whole picture of the education situation of migrant students, as school choices are not random even among public schools. There might be a sorting of students based on family background to schools with different qualities. To examine this, we construct a school quality index and confirm that for both migrant and local students, those with a better family background are sorted into higher-quality schools. In addition, we also find that migrant students are less likely to enter better public schools.

Sorting across schools occurs as parents with better socio-economic backgrounds make extra effort to enroll their children into higher-quality schools or with lower ratios of migrant students. The latter happens when parents, especially local parents, think that migrant student classmates would exert negative peer effects on other children. Therefore, it is important to examine whether exposure to a higher fraction of migrant students causes lower student achievement. We find that the proportion of migrant students is negatively correlated with school average test scores, but this correlation is mainly due to the difference in school quality and student family background. We do not find evidence of a negative peer effect of migrant students either at the school level or the class level.

Outlook

In terms of public policy, our results suggest that to improve the educational prospects of migrant children, governments should do two things. First, they should allow more migrant students to enroll in public schools and especially the higher-quality public schools. Second, they should also help migrant schools improve through offering more financial subsidies to offer a level playing field. What happened in Shanghai since 2010 shows that these are feasible and effective options for other cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen to consider.

However, since 2013, there have been stricter population controls in super-cities. Shanghai, without exception, has dramatically strengthened various population control measures, including imposing more stringent school enrollment requirements on migrant students. As a result, school enrollments of migrant students in Shanghai decreased sharply from 2013 to 2014 and remained at a much lower level than before. We argue that this is not a virtuous education policy, as many students were forced to go back to their home villages and became "left-behind children;" some even had to drop out of school. On the other hand, this may not be a very effective population control policy, as many parents stayed in the city to work while separated from their children.

(Yuanyuan Chen, School of Economics, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics; Shuaizhang Feng, Institute for Economic and Social Research, Jinan University.)

Chen, Yuanyuan and Shuaizhang, Feng, “Quality of migrant schools in China: evidence from a longitudinal study in Shanghai,” Journal of Population Economics, 2017(30), 1007-1034. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-016-0629-5.

Chen, Yuanyuan and Shuaizhang, Feng, “Access to public schools and the education of migrant children in China,” China Economic Review 26, 2013, 75-88. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043951X13000400.

Feng, Shuaizhang Yuanyuan Chen and Jiajie Jin, “The future of cities: The Shanghai model of migrant children’s education,” Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press, 2017. http://spu.dangdang.com/1032007457.html.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email