Early Childhood Exposure to Health Insurance and Adolescent Outcomes: Evidence from Rural China

We examine the impact of early-life exposure to public health insurance, the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS), on outcomes in adolescence in rural China. We find that exposure to the NCMS between ages zero and five significantly improves health, cognitive, and educational outcomes during adolescence. In contrast, exposure after age five has no significant effects.

More than 200 million children under five years of age in the developing world fail to reach their developmental potential due to poverty, poor health, malnutrition, and deficient care (Grantham-McGregor et al. 2007). Because of liquidity constraints and the high cost of healthcare among the poor (World Health Organization 2002), the lack of accessible and affordable healthcare may be an important reason.

The literature has shown that the provision of public health insurance in early life can generate long-lasting benefits in developed countries. Given the different settings between industrial and developing countries, the estimates and the possible mechanisms found in this literature may not be applicable in the developing world. However, the related evidence on the longer-term benefits of public health insurance among children is very thin in these countries. Since the governments of many low- and middle-income countries are considering expanding (or have just expanded) public health insurance programs (World Health Organization 2010), empirical evidence is also important for policymakers to evaluate these programs.

In a recent study, we try to answer the following questions in the context of rural China: 1) whether and to what extent exposure to public health insurance in early life affects health, cognitive, and education outcomes approximately ten years later (i.e., in adolescence); and 2) what possible mechanisms underlie the effects of early-life exposure to health insurance.

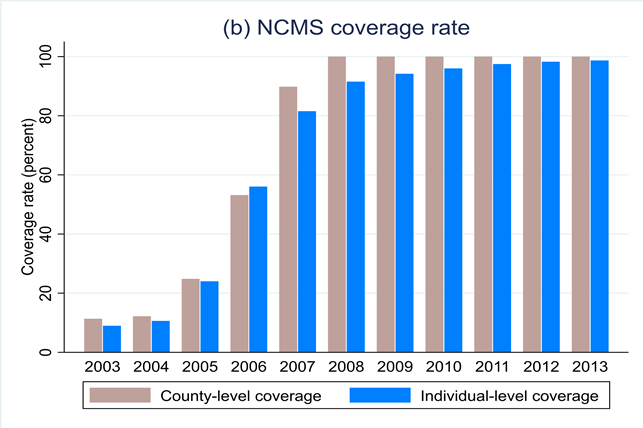

As of 2004, China has about 15 million disadvantaged children—the third-largest number in the world—and most of them living in rural areas (Grantham-McGregor et al. 2007). The Chinese government introduced a nationwide, heavily subsidized public health insurance program known as the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) for rural residents in 2003. As shown in Figure 1, the program expanded rapidly to 310 rural counties (11 percent of all rural counties) in 2003, to 678 counties (25 percent) in 2005, to 1451 counties (53 percent) in 2006, and to almost all counties in 2008. By 2011, the NCMS covered 832 million rural residents (98 percent of the rural population, including children, pregnant women, older adults, and other rural residents) and amounted to 171 billion RMB (approximately 24.4 billion USD) in government spending, which accounted for 7% of total health spending and 0.4% of GDP in China. Insured residents benefit from reimbursement of hospitalization expenses as well as partial reimbursement of outpatient expenses.

Figure 1. NCMS coverage over time

Notes: Data are from China Health Statistics Yearbook 2009–2014.

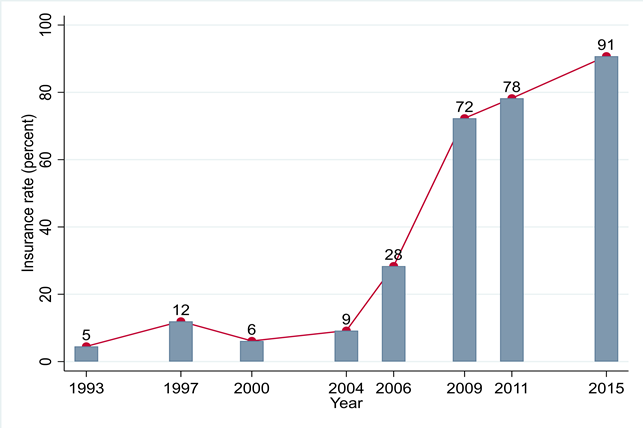

Figure 2 illustrates the substantial increase in public health insurance coverage among rural children between age zero and five since the introduction of the NCMS, using data from China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) 1993–2015. Over this period, the proportion of rural children with public health insurance increased from 5% to 91%.

Figure 2. NCMS insurance coverage among rural children ages 0–5

Notes: Data are from China Health and Nutrition Survey 1993–2015.

We first evaluate whether exposure to NCMS in early life (defined as the period from conception to age five) improves a wide variety of health, cognitive, and educational outcomes in adolescence (ages 10–19) using the longitudinal microdata of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) from 2010 to 2016. We exploit the temporal and geographical variations in the county level rollout of the NCMS, which we collected from various public reports of central and local governments, to identify the effects. We focus on rural cohorts born between 1991 and 2007, consisting of seven cohorts that had no exposure to NCMS during their early-life period and ten cohorts that were exposed starting at some point in their early-life period. Cohorts who were born one year after the introduction of the NCMS in the county are considered fully exposed, while those ages six and above in the reform year of each county are defined as nonexposed.

We find that early-life exposure to the NCMS has considerable longer-term effects on adolescent health, verbal test scores, and educational outcomes. Full exposure in utero to age five is associated with a 0.28 standard deviation improvement in health (measured by a composite index combining information on self-reported health, hospitalization, and underweight) and a 0.32 standard deviation increase in cognition (measured by verbal test scores) among rural adolescents. In addition, such full exposure leads to a 13.4 percentage point higher likelihood of school enrollment and one more year of education in adolescence. Furthermore, we also find that girls benefit more from the program than boys in terms of cognition and educational outcomes and that the poorer group benefits more in terms of health and educational outcomes. Compared to Medicaid in the US, NCMS has relatively lower financing and reimbursement rates, but NCMS exposure in early life has similar health gains and larger educational benefits (Boudreaux, Golberstein, and McAlpine 2016, Cohodes et al. 2016, Miller and Wherry 2019). This may be understandable because children in rural China generally have lower education status than those covered by Medicaid in the US.

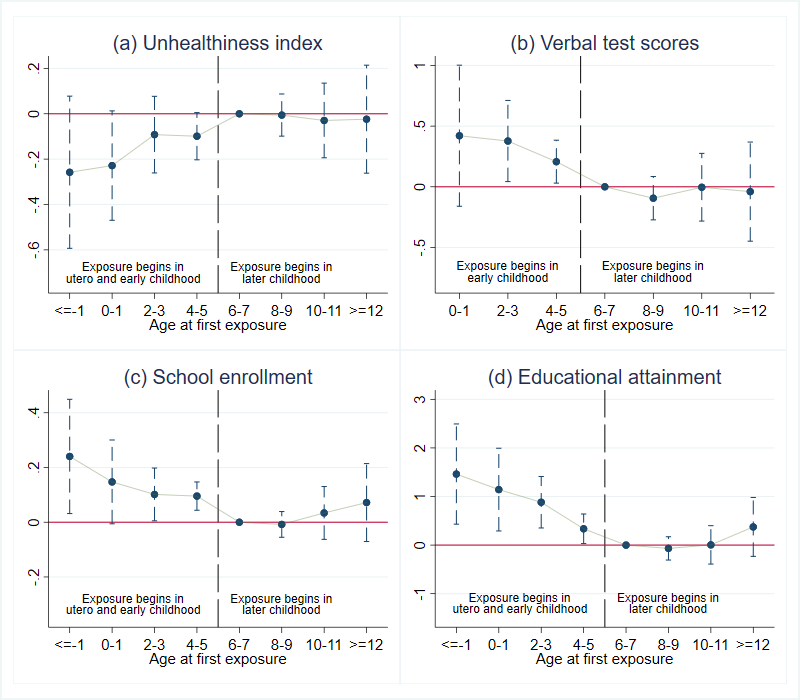

Additionally, Figure 3 shows that the beneficial effects of the NCMS are salient among those exposed during the period before age five, with little or no impact for those exposed in later childhood (i.e., ages six and above). We also conduct a back-of-the-envelope calculation to quantify the induced benefits we estimate above. The total benefits, including the lower cost from less hospitalization (i.e., 4,800 RMB or 685 USD per person) and the higher expected gains from improved health and higher education (i.e., 1,500 RMB or 215 USD per person), far exceed the total financing cost of the NCMS coverage during early childhood (i.e., 3,000 RMB or 430 USD per person).

Figure 3. Effects of NCMS by age at first exposure for girls

We further investigate several potential mechanisms underlying the above longer-term benefits of the NCMS by investigating the contemporary impacts of the rollout of the NCMS on a series of outcomes among rural children at ages zero to five. We make use of longitudinal data before and after the introduction of the NCMS from the CHNS and retrospective data from the CFPS to explore these mechanisms. First, we find that the NCMS introduction is associated with a significant increase in prenatal care among mothers as well as a substantial improvement in birth weight. Meanwhile, we find no significant impacts of the NCMS on fertility, suggesting that the improvement in birth outcomes should not be driven by birth selection. In addition, the NCMS increases the contemporaneous utilization of preventive care and lowers the likelihood of being sick or injured among children ages zero to five. Furthermore, the program also reduces exposure to catastrophic medical spending, improves durable consumption, and increases maternal time input and expenditure on childcare for households with children ages zero to five. Finally, we also find suggestive evidence that NCMS eligibility in early childhood is associated with more significant household wealth accumulation and more educational investments in the longer run.

Our findings provide some insights relevant to policy debates about whether to expand subsidized health insurance for informal sectors, especially children, in the developing world and may add to the discussion about the short- and long-term impacts of public health insurance expansion for relatively poorer people in developed countries. Our findings on outcomes in early childhood and adolescence help to understand how public insurance coverage and other interventions in early childhood affect later adult outcomes. Furthermore, our analysis provides evidence informing the question of critical ages to intervene and suggests that providing insurance coverage in early life could yield much higher returns than coverage in later childhood.

(Wei Huang, National School of Development, Peking University; Hong Liu, School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China)

References

Boudreaux, Michel H., Ezra Golberstein, and Donna D. McAlpine. 2016. “The Long-Term Impacts of Medicaid Exposure in Early Childhood: Evidence from the Program’s Origin.” Journal of Health Economics 45 (1): 161–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.11.001.

Cohodes, Sarah R., Daniel S. Grossman, Samuel A. Kleiner, and Michael F. Lovenheim. 2016. “The Effect of Child Health Insurance Access on Schooling: Evidence from Public Insurance Expansions.” Journal of Human Resources 51 (3): 727–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26449870.

Grantham-McGregor, Sally, Yin Bun Cheung, Santiago Cueto, Paul Glewwe, Linda Richter, Barbara Strupp, and the International Child Development Steering Group. 2007. “Developmental Potential in the First 5 Years for Children in Developing Countries.” Lancet 369: 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4.

Huang, Wei, and Hong Liu. 2023. “Early Childhood Exposure to Health Insurance and Adolescent Outcomes: Evidence from Rural China.” Journal of Development Economics 160, 102925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102925.

Miller, Sarah, and Laura R. Wherry. 2019. “The Long-Term Effects of Early Life Medicaid Coverage.” Journal of Human Resources 54 (3): 785–824. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.3.0816.8173R1.

World Health Organization. 2002. “Better Health for Poor Children.” https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FCH-CAH-02.5.

World Health Organization. 2010. “Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage.” https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564021.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email