Demand for Retirement Insurance: What Do People Want?

China’s social security system provides a basic pension and limited coverage for health and long-term care risks. With a rapidly aging population, the system is under pressure and private insurance markets are still underdeveloped. Using a survey experiment of retirement insurance preferences in China, we show that people prefer critical illness and long-term care coverage for half of their expected costs, along with a modest monthly pension. Access to health-contingent insurance could encourage annuity purchases. Financial capabilities and preferences (e.g., risk aversion and bequest motives) are associated with greater demand for health-contingent insurance but lower demand for life-contingent insurance (i.e., annuities).

Upon retirement, individuals need sufficient financial resources to maintain their standard of living and protect against financial and health-related risks. By 2024, about 19% of China’s population was aged 60 or above, with this figure expected to be over 40% by 2050 (United Nations 2024). Traditional family support for older people has weakened due to rapid economic development, while China’s social insurance system offers only basic coverage, and the private retirement insurance market remains underdeveloped.

The amount of the public pension for urban workers dropped from about 80% of a worker’s preretirement wage in the 1990s to around 45% of the local average wage in 2019, and private pension coverage is low (Fang and Feng 2020). Public health insurance often excludes costly drugs and medical treatments, leading to catastrophic out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses for those who seek them (Liu, Vortherms, and Hong 2017). Private health insurance typically imposes age limits, excluding older adults, and long-term contracts are rare. Public long-term care (LTC) insurance is still in the pilot stage, while private options usually provide lump-sum benefits and are investment-oriented (Huang, Zhang, and Zhuang 2019). Despite recent initiatives to develop critical illness (CI) and LTC insurance, as well as retirement income (Xinhua 2020), China’s market remains underdeveloped. Understanding the demand for retirement insurance is thus of first order importance to address China’s looming aging population problem.

How to elicit the stated demand for retirement insurance

We conducted an online survey to explore the demand for retirement insurance—specifically annuities, CI insurance, and LTC insurance—in urban China. The survey was fielded in 2020 by commercial panel provider DataSpring, who recruited 1,000 participants from its database of over one million Chinese urban residents and their network of panel suppliers. We selected participants aged 45–59 (female) and 55–69 (male), residing in 52 major cities in China, in an urban hukou, who were not retired and who were in good health. We set quotas for gender, age, and city size to ensure that our sample was representative. Participants were provided hypothetical retirement savings based on their reported wealth, which they then allocated to three retirement insurance products and a savings account and chose portfolios that addressed longevity risk (annuities) and health-related risks (CI and LTC insurance). Annuities offered steady income for life, CI insurance in a lump sum upon first diagnosis, and LTC insurance as regular income for as long as the insured required care.

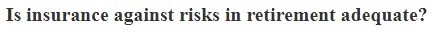

The experiment comprised two stages. In Stage 1, participants selected their preferred monthly annuity income, given each of nine preset levels of coverage for out-of-pocket CI and LTC costs, which they purchased using some or all of their assigned wealth. In Stage 2, participants ranked their nine portfolios (of retirement insurance coverage) using a best-worst scaling method to reduce cognitive load (Flynn et al. 2007; Louviere, Flynn, and Marley 2015). An overview of the survey design is shown in Figure 1. This approach allowed us to examine preferences for combinations of retirement insurance coverage and assess whether covering health-related risks (CI and LTC) could free up precautionary savings to buy longevity insurance (annuities). We also analyzed how insurance demand varied by personal characteristics.

Figure 1. Survey overview.

What type of retirement insurance do people want?

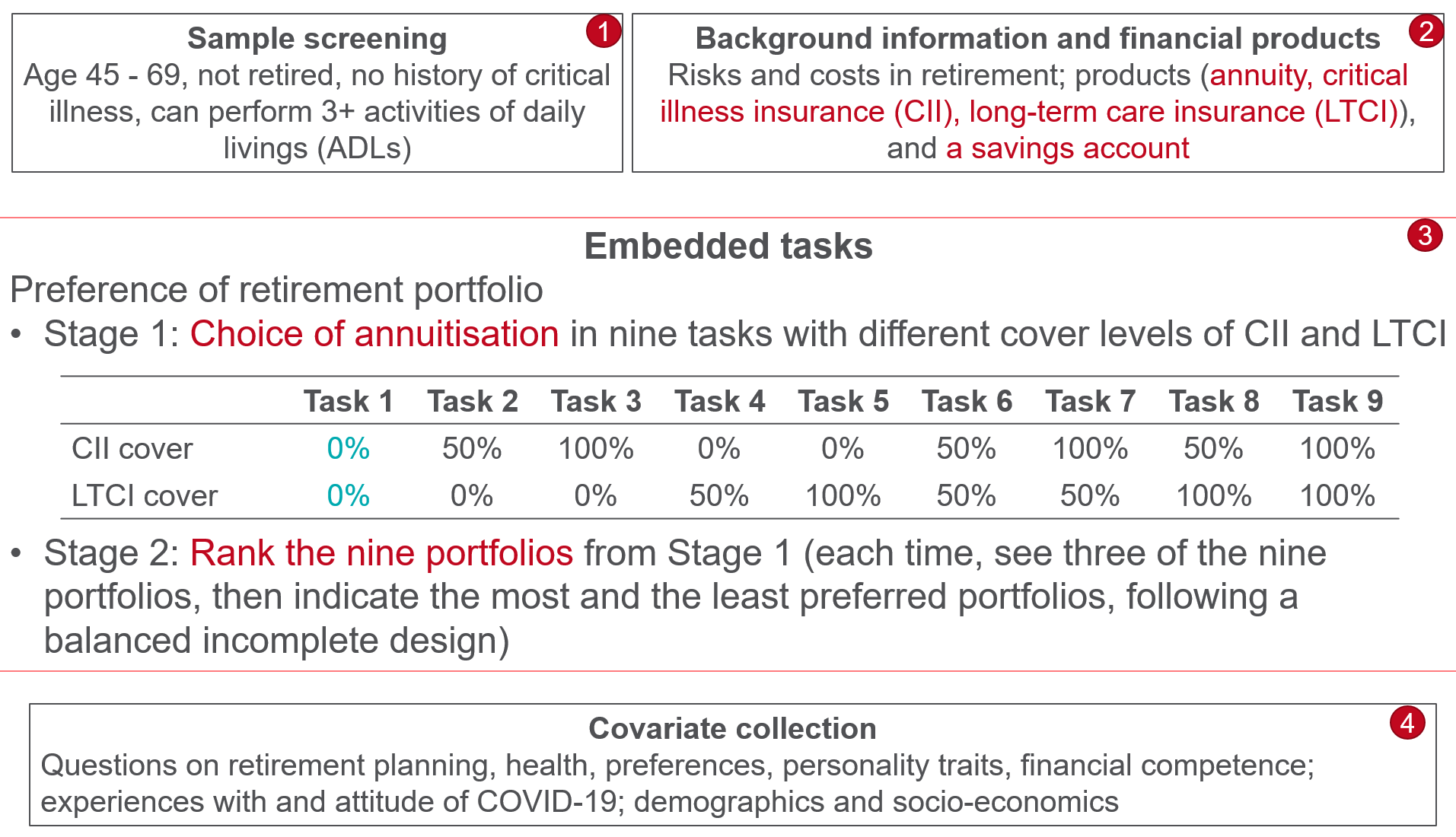

We found that most participants preferred portfolios that include more than one type of retirement insurance, while keeping a substantial portion of their retirement wealth in a liquid savings account. The most favored combination was Portfolio 6 (shown as Task 6 in Figure 1). This comprised insurance coverage for 50% of the expected OOP costs for CI and LTC, along with an annuity providing a monthly income of CNY 711 (equivalent to around 20% of the average urban disposable income in China). In this portfolio, about 42% of retirement wealth was retained in a savings account. The least preferred option was Portfolio 1 (Task 1 in Figure 1), which offered no coverage for out-of-pocket CI and LTC costs and provided an average monthly annuity of CNY 665. See Figure 2 for details. However, Portfolio 1 also showed the greatest preference variation among the nine options.

Figure 2. Preference for retirement portfolios by best-worst (B-W) measures

Notes: The CI-LTC Cover column shows the coverage (in percentage points) provided in a portfolio for expected out-of-pocket costs of critical illness (CI) and long-term care (LTC), respectively. The monthly annuity column reports the average selected annuity income (CNY) by CI-LTC coverage. The graph on the right reports the best-worst (B-W) measures for the portfolio choices.

Our regression analysis revealed that, compared to the control group (Portfolio 1, with zero coverage for OOP CI and LTC costs), bundling CI and LTC coverage can free up precautionary savings for the purchase of annuities. This finding extends the work of Reichling and Smetters (2015) and Peijnenburg, Nijman, and Werker (2017), who also explored the “annuity puzzle” in the context of health risks but did not examine whether increased health-contingent insurance coverage would boost annuity demand. Our results indicate that the effect varies with the level of coverage. For instance, 50-50 coverage (50% coverage for both CI and LTC) was associated with an increase in monthly annuity income of CNY 45–53 (p < 0.01). Conversely, 100–100 coverage was associated with a reduction in the monthly annuity of CNY 76 (p < 0.01), likely because higher coverage for CI and LTC leaves less savings for the purchase of annuities.

How are personal characteristics associated with retirement insurance demand?

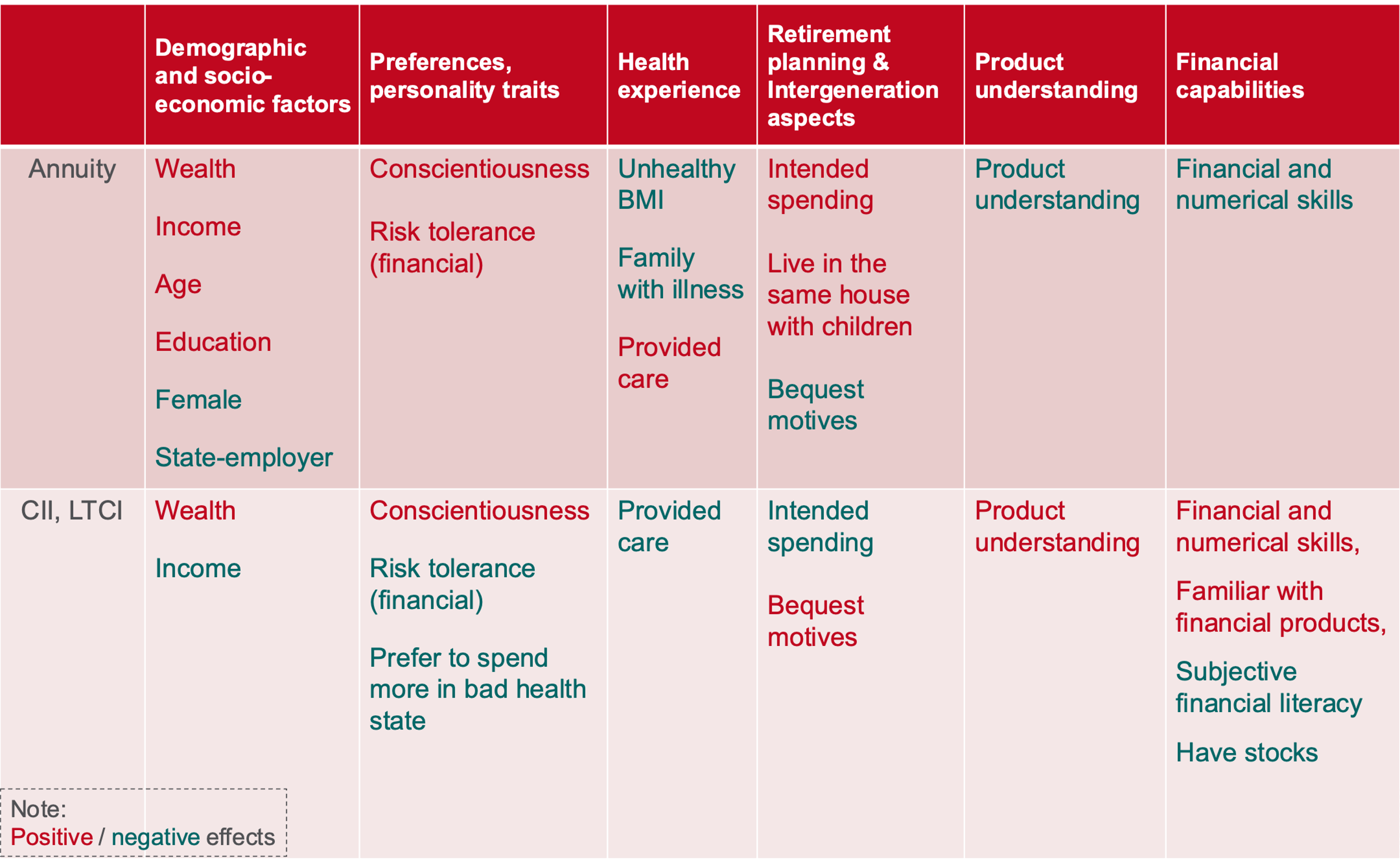

Our findings reveal that retirement insurance preferences are closely tied to individual circumstances, indicating that “one-size-fits-all” solutions are not suitable for addressing coverage gaps. We observed significant variation in how retirement wealth is allocated between longevity and health-related insurance. Figure 3 illustrates how different personal factors influence insurance preferences.

Consistent with earlier research (e.g., Ying et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2017; Bateman et al. 2018; Alonso-García et al. 2022), we found that higher wealth, better financial skills, greater understanding of retirement insurance products, and higher conscientiousness were associated with a preference for more CI and LTC coverage. On the other hand, greater financial risk tolerance and a higher intention to spend more in retirement were linked to lower demand for such coverage. We also found that higher income was associated with a lower demand for health-contingent insurance, suggesting that people might rely more on self-insurance for health costs (e.g., Pang and Warshawsky 2010; Ameriks et al. 2020). Additionally, stronger bequest motives were linked to a preference for health-contingent insurance to protect assets for inheritance. Finally, unlike some previous studies (Hendren 2013; Braun, Kopecky, and Koreshkova 2019), we found minimal evidence of selection effects in the health and LTC insurance markets.

Our findings also revealed variations in demand for annuities compared to CI and LTC insurance, highlighting the distinct effects of personal characteristics and preferences on each type of coverage. Firstly, individual preferences and financial knowledge alone can distinguish between markets for longevity and health-related insurance, regardless of health status. Financial risk tolerance (Dohmen et al. 2011) was positively linked to annuity demand, but negatively associated with CI and LTC coverage. Conversely, bequest motives (e.g., Lockwood 2018), general financial skills (e.g., van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie 2011; Lusardi and Mitchell 2011), and understanding of retirement financial products (Bateman et al. 2018) were negatively associated with annuity demand, but positively linked to demand for CI and LTC insurance.

These results suggest that individuals may view annuities as risky investments while considering CI and LTC insurance as essential risk management tools. This supports the idea that people might be too risk-averse to purchase annuities (Bommier et al. 2020) and indicates that in developing countries, people prioritize health-related risks over longevity risks.

Furthermore, we observed potential selection effects for annuities based on objective health measures such as BMI, but these effects did not extend to the health-contingent insurance we studied.

Figure 3. Factors affecting demand for annuities, CI, and LTC insurance.

Notes: Red text indicates that the factor has a positive association with the demand for annuities, or CI and LTC insurance. Green text represents a negative association. The results are based on a linear mixed model for annuity demand based on the Stage 1 data and a multinomial logit model for the preference for coverage of expected OOP CI and LTC costs based on the Stage 2 data.

What are the implications?

Our results highlight a significant gap in the demand for retirement insurance in China that warrants attention from policymakers and insurers. Adverse selection and varying preferences are potential obstacles to the growth of the annuity market. However, retirees often perceive annuities as risky investments, whereas they see health-contingent insurance products as essential risk management tools, likely due to heightened concerns about health-related risks in less developed regions. Regardless of health, preferences and financial capabilities could separate the longevity and health-contingent insurance markets. Combining CI and LTC insurance with annuities could boost interest in both types of coverage. Additionally, regulators might consider framing annuities in terms of consumption to make them appear less risky, while insurers should address other behavioral factors contributing to the annuity puzzle to enhance their attractiveness (Brown et al. 2008; Beshears et al. 2014; Benartzi, Previtero, and Thaler 2011).

References

Alonso-García, Jennifer, Hazel Bateman, Johan Bonekamp, Arthur van Soest, and Ralph Stevens. 2022. “Saving Preferences after Retirement.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 198: 409–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2022.04.005.

Ameriks, John, Joseph Briggs, Andrew Caplin, Matthew D. Shapiro, and Christopher Tonetti. 2020. “Long-Term-Care Utility and Late-in-Life Saving.” Journal of Political Economy, 128 (6): 2375–2451. https://doi.org/10.1086/706686.

Bateman, Hazel, Christine Eckert, Fedor Iskhakov, Jordan Louviere, Stephen Satchell, and Susan Thorp. 2018. “Individual Capability and Effort in Retirement Benefit Choice.” Journal of Risk and Insurance 5 (2): 483–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/jori.12162.

Benartzi, Shlomo, Alessandro Previtero, and Richard H. Thaler. 2011. “Annuitization Puzzles.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25 (4): 143–64. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.4.143.

Beshears, John, James J. Choi, David Laibson, Brigette C. Madrian, and Stephen P. Zeldes. 2014. “What Makes Annuitization More Appealing?” Journal of Public Economics 116, 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.05.007.

Bommier, Antoine, Daniel Harenberg, François Le Grand, and Cormac O’Dea. 2020. “Recursive Preferences, the Value of Life, and Household Finance.” Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 2231. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3592883.

Braun, R. Anton, Karen A. Kopecky, and Tatyana Koreshkova. 2019. “Old, Frail, and Uninsured: Accounting for Features of the U.S. Long-Term Care Insurance Market.” Econometrica 87 (3): 981–1019. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA15295.

Brown, Jeffrey R., Jeffrey R. Kling, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Marian V. Wrobel. 2008. “Why Don’t People Insure Late-Life Consumption? A Framing Explanation of the Under-Annuitization Puzzle.” American Economic Review 98 (2): 304–9. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.304.

Dohmen, Thomas, Armin Falk, David Huffman, Uwe Sunde, Jürgen Schupp, and Gert G. Wagner. 2011. “Individual Risk Attitudes: Measurement, Determinants, and Behavioral Consequences.” Journal of the European Economic Association 9 (3): 522–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x.

Fang, Hanming, and Jin Feng. 2020. “The Chinese Pension System.” In Handbook of China’s Financial System, edited by Marlene Amstad, Guofeng Sun, and Wei Xiong. Princeton University Press.

Flynn, Terry N., Jordan J. Louviere, Tim J. Peters, and Joanna Coast. 2007. “Best–Worst Scaling: What It Can Do for Health Care Research and How to Do It.” Journal of Health Economics 26 (1): 171–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.04.002.

Hendren, Nathaniel. 2013. “Private Information and Insurance Rejections.” Econometrica 81 (5): 1713–62. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA10931.

Huang, Yang, Yixing Zhang, and Xiaowei Zhuang. 2019. “Understanding China’s Long-Term Care Insurance Pilots: What Is Going On? Do They Work? And Where to Go Next? Technical Note.” World Bank Group, Washington, DC. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/496061563801421452/technical-note.

Koijen, Ralph S., Stijn van Nieuwerburgh, and Motohiro Yogo. 2016. “Health and Mortality Delta: Assessing the Welfare Cost of Household Insurance Choice.” Journal of Finance 71 (2): 957–1010. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12273.

Liu, Gordon G., Samantha V. Vortherms, and Xuezhi Hong. 2017. “China’s Health Reform Update.” Annual Review of Public Health 38 (1): 431–48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044247.

Lockwood, Lee M. 2018. “Incidental Bequests: Bequest Motives and the Choice to Self-Insure Late-Life Risks.” American Economic Review 108 (9): 2513–50. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141651.

Louviere, Jordan J., Terry N. Flynn, and A. A. J. Marley. 2015. Best-Worst Scaling: Theory, Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011. “Financial Literacy around the World: An Overview.” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10 (4): 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747211000448.

Pang, Gaobo, and Mark Warshawsky. 2010. “Optimizing the Equity-Bond-Annuity Portfolio in Retirement: The Impact of Uncertain Health Expenses.” Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 46 (1): 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.insmatheco.2009.08.009.

Peijnenburg, Kim, Theo Nijman, and Bas J. M. Werker. 2017. “Health Cost Risk: A Potential Solution to the Annuity Puzzle.” Economic Journal 127 (603): 1598–1625. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12354.

Reichling, Felix, and Kent Smetters. 2015. “Optimal Annuitization with Stochastic Mortality and Correlated Medical Costs.” American Economic Review 105 (11): 3273–3320. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20131584.

United Nations. 2024. Data Portal – Population Division. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/.

Van Rooij, Maarten, Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob Alessie. 2011. “Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation.” Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2): 449–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.006.

Wang, Qun, Yi Zhou, Xinrui Ding, and Xiaohua Ying. 2017. “Demand for Long-Term Care Insurance in China.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (1): 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010006.

Xinhua. 2020. “China to Refine Financial Services, Promote Steady Development of Personal Insurance. Xinhuanet. Available at http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-12/10/c_139576970.htm.

Ying, Xiao-Hua, Teh-Wei Hu, Jane Ren, Wen Chen, Ke Xu, and Jin-Hui Huang. 2007. “Demand for Private Health Insurance in Chinese Urban Areas.” Health Economics 16 (10): 1041–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1206.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email