How Do Public Pensions Affect Eldercare Mode and Son Preference? An Empirical Study on the New Rural Pension Scheme in China

How do public pension schemes reshape eldercare and social norms with son preference? Using variations in the timing of the New Rural Pension Scheme (NRPS) across rural Chinese counties, we examine its effects on eldercare mode, child investment, and son preference. Our findings are threefold: (1) After the introduction of NRPS, married sons are less likely to live with and provide care for their parents, while married daughters show no significant change in their caregiving behavior; (2) Parents reduce the bride price for their sons but not the dowry for their daughters; (3) The sex ratio at birth becomes more balanced, indicating a reduction in son preference. These results suggest that public pension programs can significantly influence traditional family dynamics, including eldercare modes and cultural norms around gender preference.

The eldercare mode is an important determinant of not only economic decisions such as labor supply and saving behaviors (Laitner 1988), but also family behaviors such as eldercare provision (Bonsang 2009), child investment (Becker, Murphy, and Spenkuch 2016; Bau 2021), and fertility choices (Cremer, Gahvari, and Pestieau 2011). In rural China, due to low incomes and limited savings, elderly individuals rely heavily on their family members, especially adult children, for old-age support. Particularly, married sons and their wives (daughters-in-law) traditionally bear the major responsibility of providing eldercare to parents. They are more likely to co-reside with parents and provide both physical and financial support, while married daughters typically move out. This patrilocal eldercare mode is accompanied by the high bride price paid by the groom’s parents to secure eldercare services through the daughter-in-law. Besides, the son-dependent eldercare contributes to a strong son preference and skewed sex ratio at birth.

Over the past two decades, China has been building its nationwide social security system, especially the pension and health care program, which has had a broad impact, including health, labor supply, migration, income, and so on (Huang and Zhang 2021, Shan and Park 2023). In this paper, we study the impact of the New Rural Pension Scheme (NRPS), a pension reform in rural areas, on family arrangements and the son preference social norm.

The NRPS allows rural residents aged 16 and above to voluntarily participate, with premiums paid continuously until eligibility for pension benefits at age 60. Pension amounts, partly funded by individual contributions and partly by the government, provide significant support for elderly rural residents, with the basic pension benefit at 30% of the median per capita income of rural households. The NRPS was initiated in 2009. Driven by strong financial support and political incentives, it expanded unexpectedly quickly and achieved national coverage by the end of 2012 after four rounds of expansion. We utilize the staggered county-by-county rollout of NRPS and the comparison between rural and urban areas to conduct a triple-difference (DDD) estimation on the effects of NRPS on the intra-household arrangements related to eldercare mode.

We first develop a conceptual framework to demonstrate that the introduction of NRPS provides parents with an alternative to the traditional eldercare mode by enabling them to purchase formal care, making them less reliant on their children, especially married sons and their wives. Married sons, hence, are expected to be less likely to live with their parents and provide physical help. Considering that bride price is a means of securing eldercare services through daughters-in-law, reducing son-dependent eldercare may decrease the bride price for their sons. At the same time, pension benefits may also affect fertility decisions; because of the weakened importance of sons in the eldercare mode, sex selection in children’s birth will be reduced.

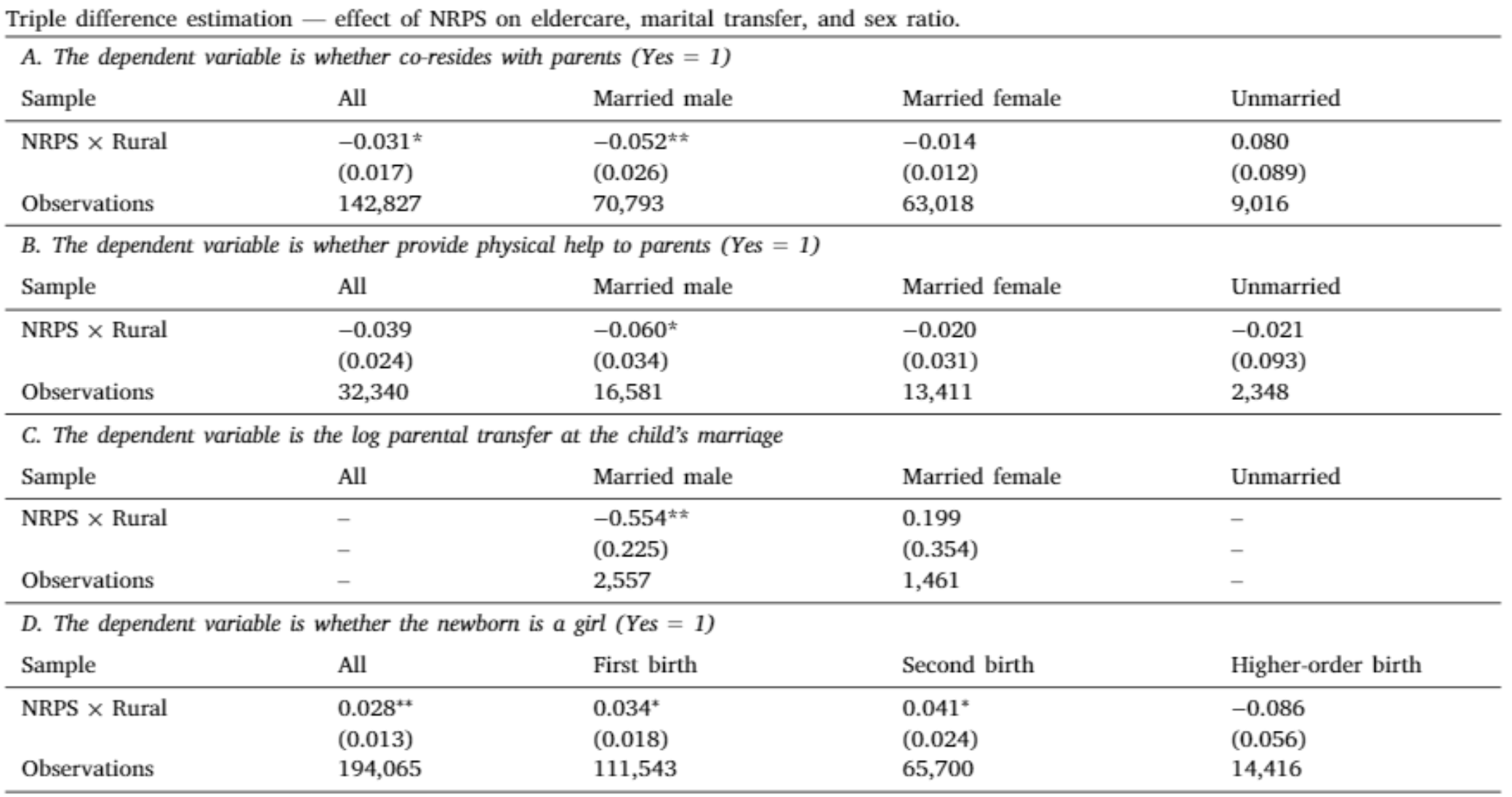

Using three waves of data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Studies (CHARLS 2011, 2013, and 2015), four waves of data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016), and microlevel data from the 2015 mini census, we offer the empirical findings summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.

First, in counties that have implemented NRPS, children are less likely to live with or provide physical help to their parents, especially after marriage. In addition, these negative effects on co-residence and physical help are mainly observed among married male children but not married female children. As shown in Panel A of Table 1, the introduction of NRPS leads to a 5.2 percentage point (ppt, 17.8%) reduction in the likelihood of co-residence with parents for married sons, while it does not significantly affect married daughters. Furthermore, as shown in Panel B of Table 1, the likelihood that married sons will provide physical help to their parents is reduced by 6.0 ppt (42%), whereas the effect on female children is not statistically significant.

Aside from the effects of the pension program on eldercare received by aging parents, we find that the pension also affects the decisions of young parents. Panel C of Table 1 shows that the NRPS leads to a 55.4% decline in the bride price given by the son’s parents, but no significant effect on the dowry given by the daughter’s parents. Furthermore, Panel D of Table 1 demonstrates that the introduction of the pension scheme results in a 2.8 ppt increase in the likelihood of a newborn being female in rural areas compared to urban areas, equivalent to a 12.7 ppt (10.7%) decrease in the sex ratio.

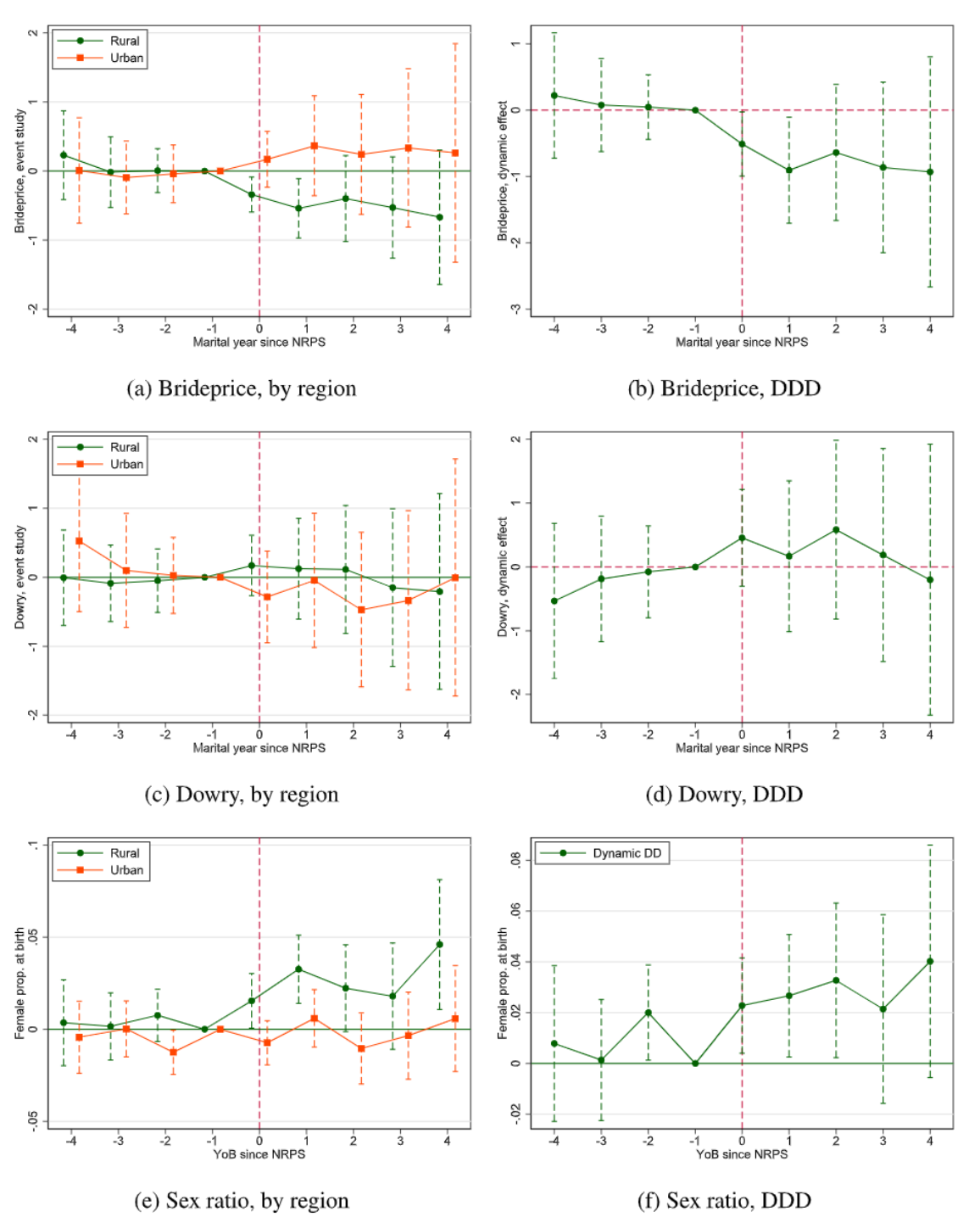

We have done several robustness checks. First, we conducted a balance test to determine whether counties that implemented NRPS earlier differed systematically from those that implemented NRPS later. We demonstrate that counties in the final wave are more economically developed than those in earlier waves. Nevertheless, we show that prior to 2009, counties with different NRPS implementation years had comparable trends in terms of a range of macroeconomic indicators, such as GDP per capita, salary, and population, as well as the number of primary school, high school, and college students. Moreover, we implemented an event study analysis to test the parallel trends assumption and to explore the dynamic effects of the NRPS over time, as shown in Figure 1. The event study results reveal no significant differences in pretreatment trends for marital transfers and sex ratio across counties, confirming the parallel trends assumption. We further performed separate DD analyses for rural and urban samples to verify that the observed effects of the NRPS are predominantly driven by changes in rural areas. Figure 1 further shows that there are no significant pretrends for these outcomes and the impact of NRPS is persistent.

The dramatic change driven by both market forces and pension reforms in eldercare mode in China has profoundly impacted family arrangements and social norms. From the perspective of family dynamics, our research provides consistent empirical evidence demonstrating the powerful ability of pension schemes to affect Chinese families and culture. Consequently, we have derived two key policy implications from these findings.

Firstly, the implementation of pension schemes represents a pivotal strategy in modernizing eldercare practices, signifying a transition from traditional familial support structures to reliance on state-provided financial assistance. This shift underscores the evolving role of formal institutions, such as the state and financial markets, in addressing the needs of the elderly population.

Secondly, our findings suggest that social policies can shift son-preference culture. By reducing the reliance on eldercare provided by sons, the NRPS reduces son preference and promotes gender equity within families in more equal marital transfer as well as a less-biased sex ratio. This national cultural shift highlights the role of policy interventions in fostering inclusive and egalitarian societal frameworks.

Table 1

Figure 1

References

Bau, Natalie. 2021. “Can Policy Change Culture? Government Pension Plans and Traditional Kinship Practices.” American Economic Review 111 (6): 1880–1917. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190098.

Becker, Gary S., Kevin M. Murphy, and Jörg L. Spenkuch. 2016. “The Manipulation of Children’s Preferences, Old-Age Support, and Investment in Children’s Human Capital.” Journal of Labor Economics 34 (S2): 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1086/683778.

Bonsang, Eric. 2009. “Does Informal Care from Children to Their Elderly Parents Substitute for Formal Care in Europe?” Journal of Health Economics 28 (1): 143–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.002.

Cremer, Helmuth, Firouz Gahvari, and Pierre Pestieau. 2011. “Fertility, Human Capital Accumulation, and the Pension System.” Journal of Public Economics 95 (11–12): 1272–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.09.014.

Guo, Naijia, Wei Huang, and Ruixin Wang. 2025. “Public Pensions and Family Dynamics: Eldercare, Child Investment, and Son Preference in Rural China.” Journal of Development Economics 172: 103390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2024.103390.

Huang, Wei, and Chuanchuan Zhang. 2021. “The Power of Social Pensions: Evidence from China’s New Rural Pension Scheme.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 13 (2): 179–205. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170789.

Laitner, John, 1988. “Bequests, Gifts, and Social Security.” Review of Economic Studies 55 (2): 275–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297582.

Shan, Xiaoyue, and Albert Park. 2023. “Access to Pensions, Old-Age Support, and Child Investment in China.” Journal of Human Resources 59 (6): 0321-11555R3. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.0321-11555R3.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email